Jacksonville Man Who Escaped Twin Towers’ Horror Falls Victim to Senseless Street Violence After 24 Years of Quiet Survival

The fading light of a Jacksonville evening cast long shadows across the cracked sidewalks of the Northside neighborhood on November 20, 2025, as 72-year-old Ralph “Chip” McCray shuffled home from his shift at a local hardware store, his worn jacket zipped against the chill and a paper bag of groceries swinging from one hand. McCray, a man whose life had been defined by improbable escapes—from the collapsing towers of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, to the quiet rebuild of a retiree’s routine—never saw the three teenagers approaching from the alley, their figures blending into the dusk like ghosts from a forgotten corner of the city. What began as a request for directions escalated into horror: Punches thrown, kicks landed, a relentless beating that left McCray crumpled on the pavement, his groceries scattered like broken promises. By the time a passing driver pulled over and called 911, McCray was unresponsive, his body battered in an attack so savage it stole his life just hours later at UF Health Jacksonville hospital. For a man who had stared down terrorism’s face and emerged to coach Little League and dote on his grandchildren, the randomness of his end—a street corner in his own hometown—left family, friends, and a grieving community whispering the same heartbreaking question: After surviving the unthinkable, how could this be his final chapter?

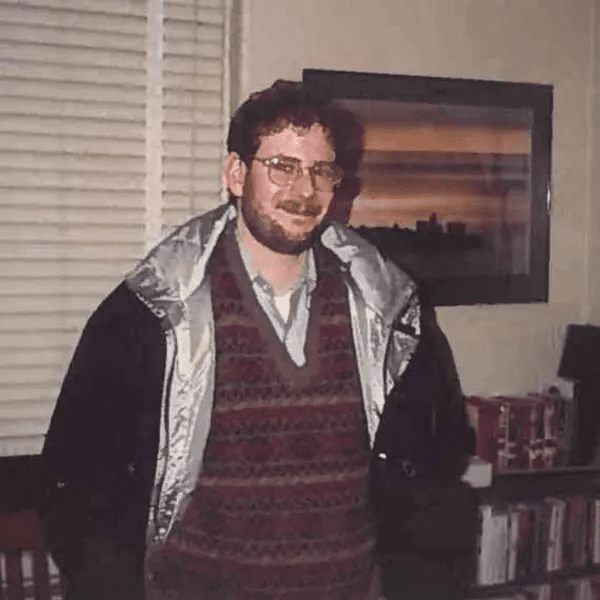

Ralph McCray’s story, one of resilience forged in fire and tempered by time, began in the steel-and-glass canyons of Lower Manhattan, where he worked as a maintenance supervisor for the Port Authority, overseeing the bustling corridors of the World Trade Center. On that fateful Tuesday morning in 2001, McCray, then 48 and a father of two, had clocked in early for a routine inspection on the 78th floor of the North Tower, his toolkit heavy with wrenches and wire cutters as he bantered with colleagues about the Yankees’ playoff chances. The first plane struck at 8:46 a.m., a deafening roar that shook the building like an earthquake, flames and debris raining down as McCray grabbed his radio and urged others toward the stairs. “Keep moving—don’t look back,” he shouted, his voice a steady anchor amid the panic, helping a group of office workers descend 78 flights in a haze of smoke and screams. Emerging into the chaos of Church Street, coated in ash and bloodied from a fall, McCray waved off medics to assist the injured, his actions earning him a commendation from the FDNY and a quiet place in the tapestry of survivor tales. “I thought that was it—then I realized it was just the start,” he told a local reporter in 2011, his eyes distant as he recalled the South Tower’s collapse, a thunder that buried friends and forever altered the skyline he loved.

The years after 9/11 reshaped McCray in ways both profound and practical, a slow rebuild from the rubble of loss. He relocated to Jacksonville in 2003, seeking warmer climes and family ties—his daughter, Lisa, had settled there with her own young family, and the move offered a fresh start away from New York’s ghosts. Taking a job at a Home Depot in the Northside, McCray found solace in the rhythm of stocking shelves and advising customers on plumbing fixes, his World Trade Center stories shared sparingly, like treasures too precious for casual telling. “Dad never complained— he coached my boy’s T-ball team, fixed neighbors’ fences for free. That day made him kinder, more present,” Lisa McCray, 42, shared through quiet tears at a memorial service on November 22, her hands clasped around a photo of her father in his Port Authority uniform, grinning beside the Twin Towers. McCray, a widower since 2018 when his wife lost her battle with cancer, poured his energy into his grandchildren—teaching them to fish off the St. Johns River, reading bedtime stories from a worn copy of “Where the Wild Things Are.” His evenings were simple: Poker nights at the VFW hall, where fellow 9/11 survivors swapped tales over cheap beer, and walks home through the Northside’s tree-lined streets, where kids played basketball under floodlights and neighbors waved from porches.

The attack that ended his life unfolded in those familiar blocks, a random eruption of violence in a neighborhood long marked by its working-class grit and occasional struggles with poverty and petty crime. McCray had just finished his 6 p.m. shift, the paper bag holding a six-pack of root beer for the grandkids and a frozen pizza for his quiet dinner, when three teenagers—aged 12, 15, and 17—approached him near the intersection of Moncrief Road and West 22nd Street. According to Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office reports, what started as a request for a lighter escalated into demands for his wallet and phone, McCray’s refusal met with fists and kicks that drove him to the ground. The assault lasted three minutes, captured on a nearby Ring camera showing the boys—two in hoodies, one in a basketball jersey—swarming him like a pack, their blows raining down on his head and torso until a neighbor’s shout scattered them into the night. “He didn’t fight back— just covered his head, yelling for help,” the neighbor, 58-year-old retiree Tom Wilkins, told detectives, his voice cracking as he described holding McCray’s hand until paramedics arrived, the older man’s breaths shallow and labored. McCray, unconscious with multiple skull fractures, internal bleeding, and a punctured lung, was rushed to the hospital, where doctors fought valiantly for six hours before calling time at 11:47 p.m.

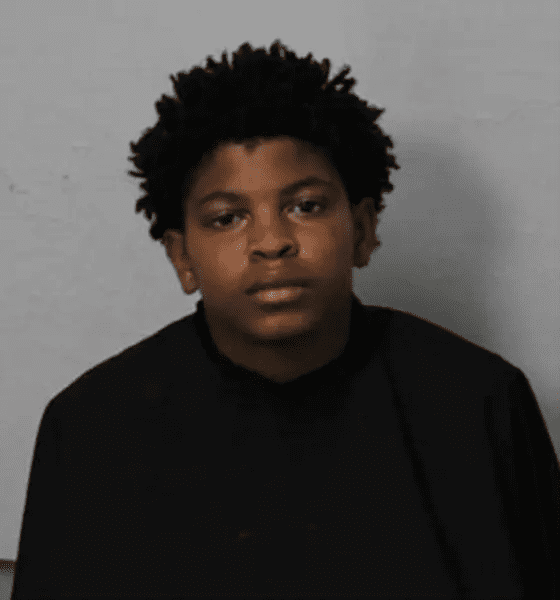

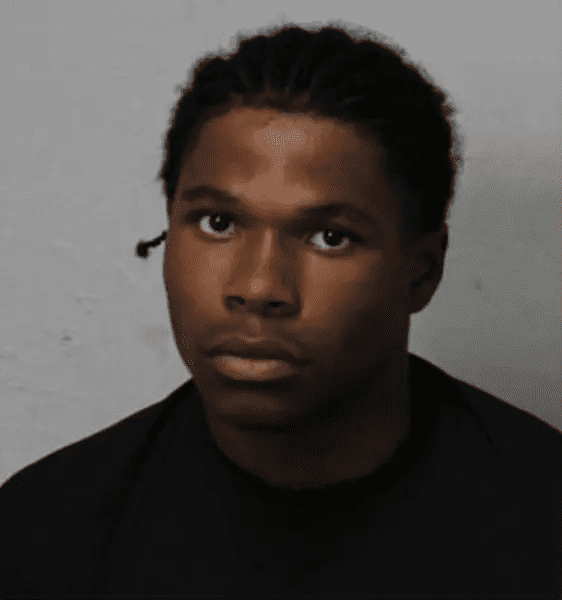

The perpetrators, arrested within 48 hours after a tip led police to a nearby apartment, face first-degree murder charges as juveniles, their identities withheld due to age but described as local teens with prior truancy records. The 17-year-old ringleader, according to affidavits, had a history of shoplifting and gang affiliations, while the younger two were repeat runaways from unstable homes. “This wasn’t planned—it was opportunity and anger, kids who needed guidance but got none,” Duval County State Attorney Melissa Almand said in a November 22 press conference, her tone a blend of sorrow and determination as she outlined the case for adult trial. The arrests, aided by surveillance footage and witness sketches, brought a measure of closure, but for McCray’s family, it felt hollow. Lisa, sifting through her father’s wallet at the funeral home—his ID still clipped to his belt loop—found a faded 9/11 survivor pin, its edges worn from years of quiet wear. “He escaped towers falling on him, only to be taken by fists on his own street. It’s not fair—none of it,” she said, her voice a whisper amid the hum of mortuary fans, her children clinging to her skirt as they placed a Lego tower in his casket, a nod to the buildings he once helped build.

Public response, from Jacksonville’s resilient neighborhoods to the national stage, wove grief with a call for reflection, a community confronting the fragility of safety in America’s aging corners. Vigils bloomed overnight: At the hardware store, colleagues lit 72 candles—one for each year of McCray’s life—forming a circle where coworkers shared stories of his patience with frazzled DIYers and his habit of slipping kids extra nails for treehouses. “Chip was the guy who’d stay late to teach you how to fix a leaky faucet—no charge, just because,” manager Elena Vasquez said, her apron still dusted with sawdust as she hugged Lisa during the gathering. The VFW hall, packed with 9/11 survivors from Florida’s survivor network, turned into a wake where tales flowed like the beers—McCray’s escape from the 78th floor, his first Christmas in Jacksonville with a tree strung with Port Authority badges. “We thought we were done with nightmares after 9/11—this brings it back, but Chip would want us to keep going,” said fellow survivor Tom Reilly, 70, his voice thick as he raised a glass to the man who “beat the odds twice, almost three times.”

Broader outrage simmered in op-eds and town halls, a nation pausing to ponder violence’s random reach. In Jacksonville, where 2025 saw a 12 percent homicide rise amid post-pandemic strains, community leaders like Rev. Jamal Bryant of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church hosted forums blending prayer with policy pleas—more youth programs, mental health funding, streetlight repairs in overlooked blocks. “Chip was a survivor, a gentle soul—his loss calls us to protect our elders, not just mourn them,” Bryant said to 500 at a Northside church, his words drawing amens from grandmothers who nodded, sharing fears of walking home alone. Social media amplified the call: #JusticeForChip trended with 1.2 million posts, blending McCray’s smiling photos—him at a grandson’s graduation, fishing the St. Johns—with demands for juvenile reform, one viral thread from a local mom garnering 500,000 views: “These kids need mentors, not mugshots—Chip would have helped them, if they’d let him.” Nationally, 9/11 groups like the Voices Center released statements honoring McCray as “a beacon of endurance,” their vigils in New York linking his story to the 2,977 lost on that day, a bridge from towers to streets where survival’s fragility endures.

For Lisa and her family, the days blur into a vigil of memories and milestones missed—Thanksgiving without Dad’s corny jokes, Christmas without his handmade ornaments. “He escaped hell once, rebuilt quietly—now he’s gone to a better place, but it hurts so much,” she said, folding his favorite flannel shirt at home, her children drawing pictures of “Grandpa in heaven with angels.” The teens’ arraignment on November 24 brought a courtroom packed with supporters, Lisa facing the accused with a composure born of loss: “They took my dad, but not his kindness— we’ll honor that.” As Jacksonville’s lights twinkle over the St. Johns, McCray’s legacy lingers—a survivor who beat the odds, only to remind us that life’s fragility demands we cherish every walk home, every shared laugh, every chance to say goodbye.