Australia to Cap Billionaire Election Spending at $20,000 Per Donor Starting in 2026

Australia has taken a bold step that is already sending ripples through its political landscape. For decades, money has played a powerful role in shaping campaigns, parties, and outcomes, and it has long been a point of debate whether wealth should have such a direct influence on democracy. But now, with sweeping reforms signed into law, the country is drawing a line in the sand. Starting from July 1, 2026, no single donor—billionaire or otherwise—will be allowed to give more than $20,000 in a year to a candidate or party division. The move has been framed by some as Australia’s strongest stand yet against the dominance of big money in politics.

The new rules are part of the Electoral Reform Act 2025, which received royal assent earlier this year after months of debate. Alongside the $20,000 cap, the reforms also slash the donation disclosure threshold to as little as $1,000, meaning contributions can no longer be quietly funneled under the radar. Real-time or near real-time reporting will also become a requirement, ensuring the public knows much sooner where the money behind their leaders is coming from. For many Australians who have watched scandals unfold around political funding, these steps feel like long-overdue guardrails.

The law isn’t only about donors—it is also about how much political parties themselves can spend. For the first time, there will be a ceiling on campaign spending: $90 million nationwide, and $800,000 for each electorate. This is meant to level the playing field, preventing elections from becoming arms races where only the deepest pockets can afford to compete. Critics say these caps still favor the major parties who have the largest war chests, but for smaller players, the rules also offer clarity about the limits of competition.

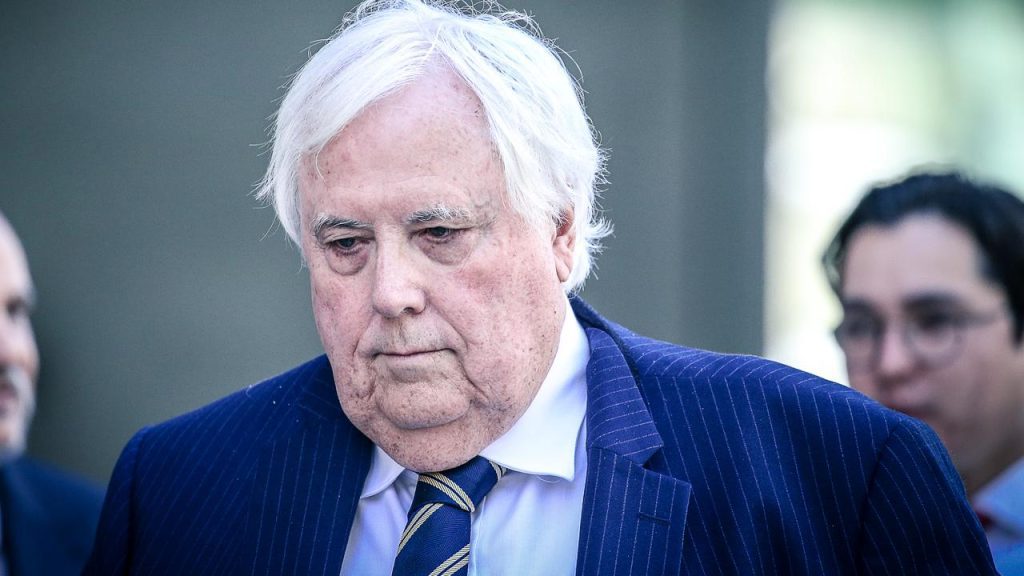

Not everyone is celebrating. The Greens and independents have warned that the legislation could entrench the dominance of the two largest parties, Labor and the Liberals, by locking in high public funding while limiting outside contributions. Mining billionaire Clive Palmer has already vowed to challenge the law in the High Court, calling it unfair and unconstitutional. For Palmer, who has spent tens of millions on his political ambitions in past elections, the $20,000 ceiling represents not just a cap, but a near-complete shutdown of his ability to self-fund campaigns in the same way.

For ordinary Australians, though, the optics matter. The idea that billionaires can no longer throw unlimited sums at candidates resonates with a public weary of the sense that politics is for sale. Even if the reforms don’t solve every problem, they send a signal that the government is at least trying to reduce the outsized influence of wealth on democracy. The challenge, as always, will be in enforcement. Watchdogs like the Australian Electoral Commission will need to ensure that donations aren’t rerouted through loopholes, shell companies, or other creative accounting tricks. Already, some critics have warned that major gaps remain, especially when it comes to third-party groups or advocacy organizations that could act as proxies for donors.

Still, the symbolism of the moment is undeniable. Australia is stepping into an era where billionaires and everyday citizens will, at least on paper, face the same rules when it comes to donating to politics. A $20,000 cap is still a significant amount of money for most people, but it is nowhere near the millions once poured into elections by the country’s richest individuals. Whether this move will actually restore faith in the system remains to be seen, but it has certainly sparked a conversation about fairness, accountability, and the role of money in public life. And in a world where trust in politics often feels fragile, even small steps toward leveling the field can feel like victories.