Chaos in Queensland: Nearly 150 Australian Students Were Excused from a Statewide History Exam After Being Taught About the Wrong Caesar — Leaving Schools and Parents Stunned

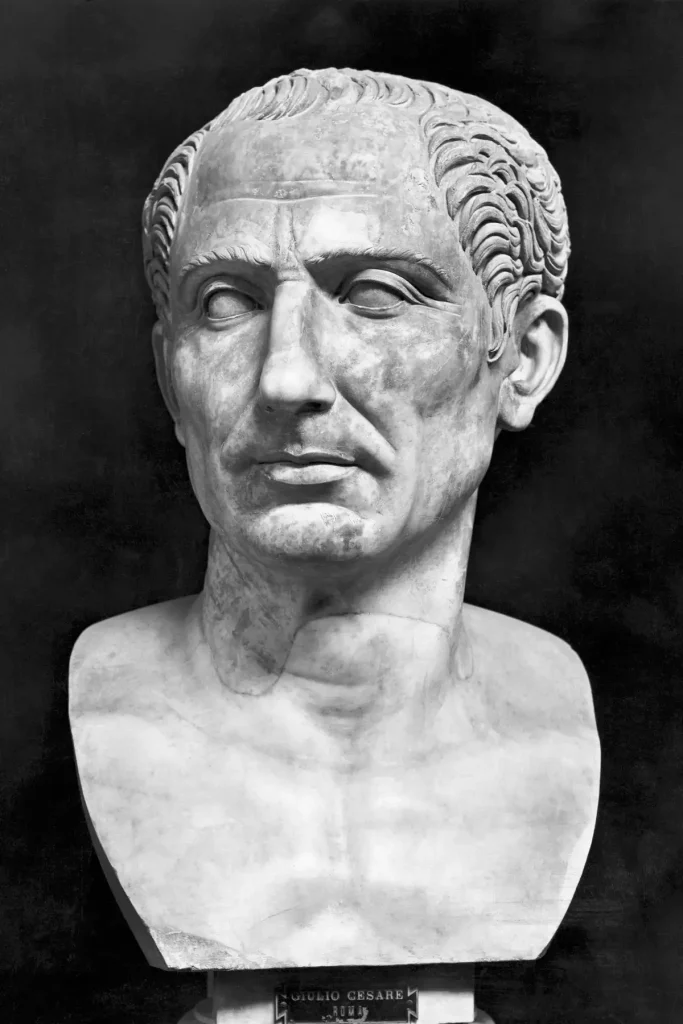

In a mix-up that sounds almost too absurd to be true, nearly 150 high school students in Queensland, Australia, were excused from taking a major statewide history exam after it was discovered that their teachers had spent months teaching them about the wrong Caesar. What was supposed to be a test on Julius Caesar — the famous Roman general, dictator, and one of history’s most studied figures — turned into a classroom full of well-prepared essays about his heir and successor, Augustus Caesar.

The confusion unfolded across at least eight schools, including some of the state’s top-performing institutions, where Year 12 students had been diligently studying the reign, reforms, and legacy of Augustus. Their mistake, however, wasn’t due to laziness or poor preparation. It was the result of a simple but consequential misunderstanding in the interpretation of the syllabus. The assessment was meant to cover Julius Caesar, the leader whose assassination in 44 BCE marked the end of the Roman Republic, not Augustus, the emperor who came after him and ushered in the Roman Empire.

By the time educators realized the error, it was too late. Students were weeks away from sitting for the statewide external history exam — an assessment that contributes to their final school results and can affect university admissions. Facing an impossible situation, the Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority (QCAA) intervened, deciding to grant the affected students exemptions from the exam altogether. Instead, their grades would be calculated based on internal coursework and teacher assessments.

The situation quickly made national headlines, not only for its rare academic blunder but also for the ripple effect it caused across the education community. Parents, teachers, and students alike expressed shock that such an oversight could happen on such a large scale. “It’s not like confusing two modern leaders,” one Brisbane parent said in a local news interview. “We’re talking about Julius Caesar — one of the most famous names in history — and somehow, they were taught about the wrong one. It’s unbelievable.”

Yet, to historians and educators, the mix-up is perhaps more understandable than it appears. The lives of Julius and Augustus Caesar are deeply intertwined, with overlapping political reforms, family ties, and even public perceptions. Augustus, born Gaius Octavius and later known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus after being adopted posthumously by Julius Caesar, became the first emperor of Rome following his great-uncle’s assassination. For students learning about the transition between Republic and Empire, the line between Julius and Augustus can seem blurred — unless clearly defined in the curriculum.

According to reports, the confusion began with a misinterpretation of the official syllabus wording, which referenced “Caesar’s leadership and legacy.” Several teachers assumed this meant Augustus Caesar, whose reign from 27 BCE to 14 CE marked the foundation of Imperial Rome. Others, however, correctly understood that the exam would focus on Julius Caesar’s role as a military and political figure in the late Republic. By the time the discrepancy was identified by exam moderators, hundreds of students had already completed months of preparation centered on the wrong man.

One Brisbane teacher, speaking anonymously, told The Courier-Mail that the mistake was “an honest misunderstanding.” “When we saw the word ‘Caesar’ without specification, many of us took it to mean Augustus,” they explained. “It wasn’t until later discussions with other schools that we realized the exam would be about Julius. It was a gut-wrenching moment — no one wants to tell their students they’ve been studying the wrong person all year.”

For the students involved, the news initially sparked panic — then, relief. Some admitted they were devastated at first, worried their months of hard work had been wasted. Others couldn’t help but see the humor in the situation. “I can’t believe we studied the wrong Caesar,” one 17-year-old told local reporters. “But honestly, I’m not complaining about missing the exam.”

The QCAA’s decision to exempt affected students from the test has been widely debated. Supporters argue that it was the fairest outcome, given that students were not at fault. Critics, however, worry that it sets a concerning precedent for academic accountability. “While the exemption is understandable, it also undermines the integrity of statewide assessments,” one education commentator noted. “It’s a reminder that clearer communication between curriculum boards and schools is essential.”

The incident also reignited broader conversations about how history is taught in schools. In an age when educational resources are increasingly digital, and teachers often rely on summarized versions of syllabi, misinterpretations can spread quickly. “This wasn’t a failure of teaching,” said Dr. Helen Marcus, a classics professor at the University of Queensland. “It was a failure of communication. Ancient history is nuanced — Caesar is not one man, but a lineage, a symbol, and a title. Without clarity, even experienced educators can make a wrong assumption.”

Indeed, the Roman legacy of the name “Caesar” only adds to the confusion. After Julius Caesar’s assassination, “Caesar” became not just a family name but an imperial title used by successive rulers for centuries — from Augustus himself to emperors of the Byzantine era. For a high school course summarizing thousands of years of Roman history, precision is everything.

Still, the story’s absurdity captured public attention worldwide, with social media users comparing it to classic mix-ups in pop culture and exam nightmares. “Imagine thinking you’re writing about Julius Caesar and spending two pages describing Augustus’ building projects,” one user joked. “Even Caesar himself would say, ‘Et tu, teacher?’”

As the dust settled, Queensland’s education officials issued a statement reaffirming their commitment to preventing similar errors in the future. “We acknowledge that the circumstances surrounding this issue were highly unusual and that students acted in good faith based on the information provided by their schools,” a spokesperson said. “We are reviewing communication procedures to ensure that syllabus content is consistently and clearly understood by all educators moving forward.”

For the affected students, the exemption was bittersweet. Some said they felt robbed of the chance to prove themselves after months of study, while others were just relieved to have their grades secured without the stress of an exam. “I feel bad for my teachers — they worked so hard with us,” one student admitted. “But at least we’ll never forget the difference between Julius and Augustus again.”

Education experts say the incident may serve as an important lesson in more ways than one. Beyond the immediate confusion, it highlights the complexity of ancient history — and how easy it is for overlapping narratives to blur even in modern classrooms. “History is not just names and dates,” Dr. Marcus said. “It’s interpretation, context, and clarity. This situation, ironic as it is, might actually make these students remember history more vividly than any test could.”

As the story spread internationally, it drew a mix of laughter and empathy. Teachers around the world chimed in online, sharing similar tales of misunderstood syllabi and mistaken topics. “Every teacher’s nightmare,” one American educator commented on X. “But also, strangely, every student’s dream — getting out of an exam scot-free.”

For now, Queensland’s education board is tightening its communication strategies, ensuring that future exam outlines are crystal clear. But in the halls of those eight schools, the incident has already become a running joke. Students reportedly refer to it as “The Great Caesar Confusion,” a phrase that will likely be remembered long after the final grades are in.

What began as a small academic oversight has now become a viral story — one that blends humor, history, and humanity. And perhaps, in its own strange way, it’s the perfect lesson about learning itself: even in the age of instant information, the smallest misunderstandings can shape the biggest outcomes.

In the end, 140 students walked away from a history exam they never took — but they might have learned a more valuable lesson than any test could measure.