Nearly 300 Federal Agents From FBI, ICE and ATF Storm Chicago Building With Blackhawks, Arresting Dozens of Suspected Illegal Immigrants Linked to Terrorist‑Designated Venezuelan Gang

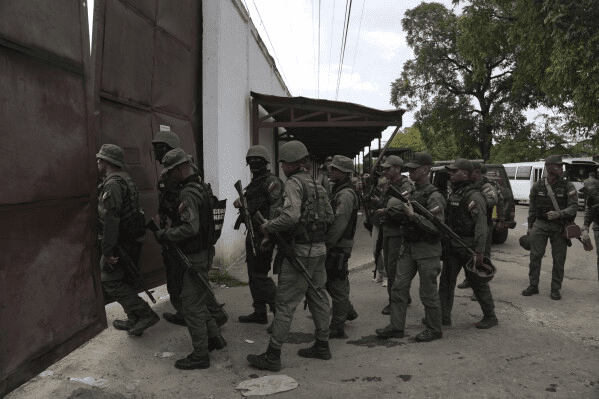

Federal agents descended on Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood in late September with the type of force usually reserved for war zones. News outlets reported that nearly 300 agents drawn from the FBI, U.S. Border Patrol, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives took part in a targeted immigration enforcement raid. While television cameras captured agents rappelling from Blackhawk helicopters onto a residential building, witnesses on the ground saw camouflage‑clad federal officers carrying long guns and wearing vests stamped “U.S. Border Patrol,” “Police” or “FBI.” The FBI later confirmed to CBS News that the dramatic operation near 75th Street and South Shore Drive was a U.S. Border Patrol targeted immigration enforcement operation, and local reporters watched as several people were led into unmarked vans.

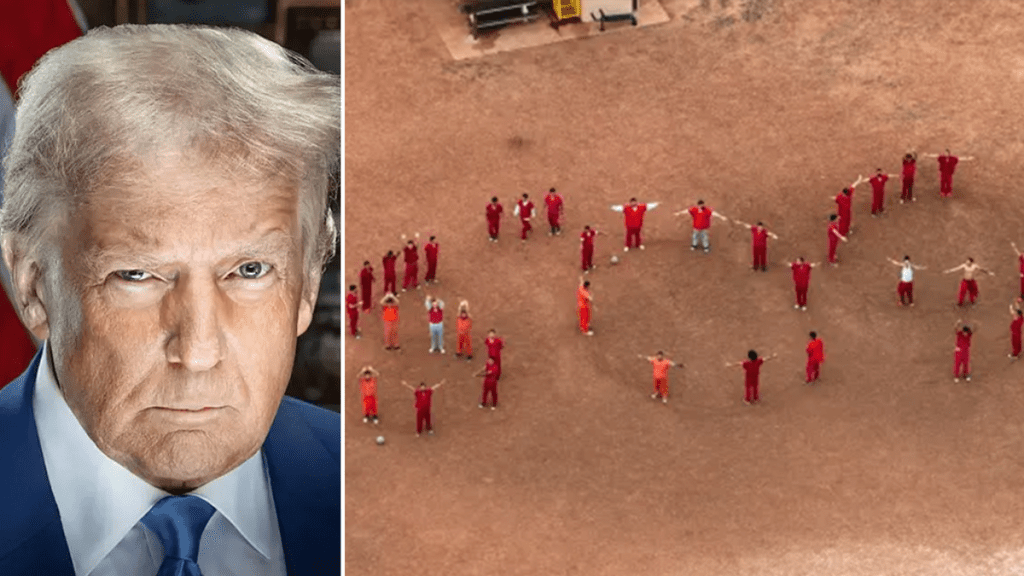

The scale of the operation underscored the federal government’s resolve to confront a rising transnational threat. Many of those taken into custody are believed to be members of Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang that U.S. authorities say has rapidly spread throughout the Americas. The Department of State notes that the gang originated in Venezuela and now has cells in Colombia, Peru and Chile, with reports of sporadic presence in Ecuador, Bolivia and Brazil. In February 2025 the State Department formally designated Tren de Aragua as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, explaining that the gang kidnaps and extorts businesses, bribes officials and has even authorized attacks on U.S. law‑enforcement officers. On his first day back in office earlier this year, President Donald Trump doubled down on that designation, labelling the gang a terrorist organization and promising a whole‑of‑government crackdown. In March, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) reported that 394 members of the gang had already been arrested and called them “rapists, drug traffickers and murderers.”

The Chicago raid is part of that broader crackdown. In April the Justice Department unsealed two superseding indictments charging 27 members and associates of Tren de Aragua with racketeering, sex‑trafficking, drug‑trafficking, robbery and firearms offenses. Federal prosecutors described the gang as a highly structured terrorist organization that has “destroyed American families with brutal violence,” forced young women trafficked from Venezuela into commercial sex work, robbed and extorted small businesses and spread a pink ketamine‑laced powder called “tusi.” They alleged that the gang operates across New York City and internationally, preserving power through murder, assault and threats. The Treasury Department has also imposed sanctions that freeze any U.S.‑linked assets of Tren de Aragua members, aiming to cut off the gang’s financial lifelines.

Back in Chicago, the scene at South Shore reflected the seriousness of this fight. According to CBS News, federal agents arrived overnight and set up U‑Haul and Budget rental trucks as staging areas. They moved in and out of the building as women and children were escorted to waiting vans. Officials haven’t released a tally of arrests, but local reports say dozens of people were taken into custody. Illinois governor J. B. Pritzker and Chicago mayor Brandon Johnson later issued statements acknowledging the federal operation and urging calm. The mayor emphasized that no widespread enforcement was planned against Chicago residents; rather, federal authorities were pursuing specific targets linked to violent crime. The presence of heavily armed federal officers nonetheless rattled neighbors, many of whom have felt caught between a surge of gang‑related violence and a political battle over sanctuary policies.

The Trump administration has defended the use of such large‑scale raids. During a March press release, DHS noted that members of Tren de Aragua are responsible for the brutal murders of Georgia nursing student Laken Riley and 12‑year‑old Jocelyn Nungaray, crimes that galvanized support for tougher enforcement. Attorney General Pamela Bondi said in April that the latest indictments would “devastate TdA’s infrastructure as we work to completely dismantle and purge this organization from our country.” In that sense, the Chicago raid appears both punitive and preventative—aimed at removing dangerous individuals from neighborhoods while sending a message that the federal government will not tolerate transnational criminal organizations operating on U.S. soil.

There is also a legal dimension. Under federal law, Posse Comitatus restricts the use of the military for domestic law enforcement; however, National Guard and federal law‑enforcement agencies are exempt. Trump administration officials argue that designating Tren de Aragua as a terrorist organization opens additional legal tools, similar to those used against foreign extremist groups. Critics contend that these operations risk conflating immigration enforcement with counterterrorism and may sow fear among immigrant communities. Civil‑rights organizations have urged transparency about who is being targeted and why, warning that innocent people could be swept up in broad raids. For residents of South Shore and other targeted neighborhoods, though, the sight of Blackhawks overhead and armored trucks on their streets is a stark reminder of how far the federal government is willing to go to confront a gang whose violence has spilled far beyond Venezuela.

As the dust settles in Chicago, questions remain about what comes next. Federal officials have signaled that additional operations are likely as they track Tren de Aragua’s movements across the country. Communities impacted by gang violence are watching closely, hoping that high‑profile raids translate into safer streets. For immigration advocates, the challenge will be ensuring that the push to dismantle a dangerous criminal network does not erode the rights and trust of law‑abiding immigrants. What is clear is that Tren de Aragua has drawn a swift and forceful response from a government determined to dismantle it. The Chicago raid may be the most dramatic example yet, but it likely will not be the last.