A Chicago Principal Ran a Marathon to Honor Students with Disabilities — and His 9-Year-Old Son with Cerebral Palsy Became His Greatest Motivation

When Dr. Larue Fitch crossed the finish line of the Chicago Marathon, he didn’t raise his arms in triumph the way many runners do. Instead, he placed a hand over his heart, closed his eyes for a moment, and whispered something to himself that the crowd around him couldn’t hear. It was not a celebration. It was a promise. To his students. To his son. To every child he has ever looked in the eye and said, “You can do hard things.” For most people, running 26.2 miles is a test of endurance. For Dr. Fitch, it was something more sacred — a way to carry the voices of the children who inspire him every day.

Dr. Fitch is the principal of an elementary school on Chicago’s South Side. He is also a father. Those roles constantly overlap, but they collided in a life-changing way when his son, now 9 years old, was diagnosed with cerebral palsy. Before that diagnosis, Dr. Fitch was already an active runner — the kind who woke up early to lace up his shoes before work, the kind who believed movement clears the mind. But after learning his son would face lifelong physical challenges, his running took on a different meaning. It became a language of love — a way to push himself physically because his son could not. A way to show that if you keep moving forward, even slowly, you are still moving.

He began training with a new purpose — every mile dedicated not to speed or personal achievement, but to the idea that bodies deserve celebration, no matter how they move. He made a decision: if his students and his son had to fight every day to move differently than their peers, then he would run on purpose — publicly, visibly, loudly — so no one could ignore the power of that fight.

That decision grew into something larger than he imagined. One morning, while watching his son struggle through a physical therapy session, he realized that the miles he ran alone could become something shared. He signed up for the Chicago Marathon — not just as a runner, but as a symbol. He would carry the names and stories of students with disabilities from his school. He would run for his son. He would run for the children who use walkers, who ride in wheelchairs, who work twice as hard just to write their names. He would run for the kids whose challenges the world doesn’t always see.

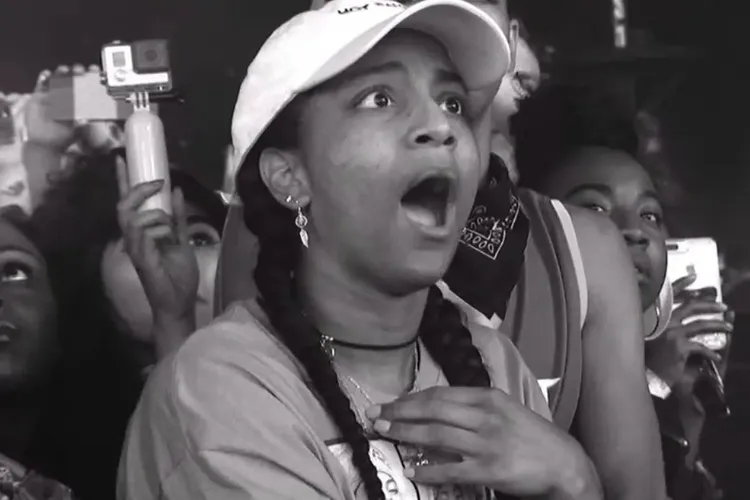

He told his staff. He told the parents. He told his students. And something extraordinary happened — the children started running with him. Not physically, but in spirit. One student gave him a bracelet and said, “Wear it so I can go with you.” Another wrote a note that said simply, “When you get tired, think of me.” He tucked that note inside his running belt on race day.

On the morning of the marathon, Chicago was buzzing with energy. Runners filled the streets. Families lined sidewalks with homemade signs. Somewhere in that massive wave of people was a principal in a blue running shirt with wings printed across the chest. He chose that shirt intentionally. Wings meant hope. Wings meant lifting. Wings meant the children he was running for could soar in their own ways.

He had trained for months, waking up before sunrise, sometimes running in silence while thinking about the paperwork waiting for him at school, the staff meetings ahead, or the next round of therapy appointments his son would attend. He trained when he was exhausted. He trained when the Chicago winter tried to bite through every layer of clothing. He trained even when he wondered if a man in his position — responsible for hundreds of children — should spend so much time on the road alone.

But every time doubt crept in, he pictured his son’s smile. He pictured the determined faces of children accomplishing something a doctor once said they might never do. He pictured the classroom where he proudly displays student artwork, including pieces from children who had to learn to hold a pencil differently, who sometimes have to relearn how to stand, how to climb steps, how to navigate a school hallway.

His son’s diagnosis arrived quietly. There was no dramatic moment — just a series of evaluations, specialists, and carefully phrased explanations. Cerebral palsy. A condition that affects movement, muscle tone, and coordination. Dr. Fitch remembers the drive home from that appointment. He stared at a stoplight for too long, thinking, “What does this mean for his future?” And then, “What does this mean for mine?”

His response was not despair. It was motion. He kept running.

At the marathon, by mile 10, his legs were ready. By mile 15, they were fatigued. By mile 20, they were screaming. He thought about the children who spend entire days focusing on one physical movement — stepping forward, gripping a pencil, raising a hand. He told himself, “If they can keep trying, I can keep running.”

Somewhere around mile 23, he started crying. Not from pain, but from memory. He remembered watching his son take three unsteady steps between railings for the first time. He remembered cheering so loudly that the therapist laughed. He remembered thinking, “This is what victory looks like in our world. Three steps can feel like 26 miles.” That moment carried him through the final stretch.

By the time he reached the finish line, hundreds of strangers were cheering, but in his mind, he heard just one voice — the little boy who once said to him, “Daddy, I wish I could run like you.” Dr. Fitch crossed the line and whispered back into the silence, “I run for you.”

After the race, he wore the medal a little differently than most people do. Instead of admiring it for what he achieved physically, he held it like a promise. The medal was a message to every child he serves: You matter. Your body matters. Your effort matters. I see you.

People later asked if he wanted to run again. He smiled and said he already runs every day. Marathon or not, he will always run. In the hallways of his school, he moves quickly from classroom to classroom, greeting students, checking in on teachers, making sure every child feels safe and known. In therapy rooms, he sits with his son and watches, learning the quiet language of resilience. On early cold mornings, he laces up his shoes and runs alone, carrying the voices of children who never asked to be brave — but are.

That is the part of the story people don’t always see. A principal’s job is heavy. A father’s love is heavier. But Dr. Fitch lifts both as if they are made of air. When he says he runs for his students, it is not a slogan. It is a way of breathing.

As news of his marathon story spreads, something beautiful is happening within his community. Parents of children with disabilities are telling him that his run made their child feel seen. Students are asking if they can start a running club. Teachers are writing notes saying they cried when they saw his finish line photo. And his son — the one who inspired every mile — asked if he could wear the medal someday.

Dr. Fitch gave it to him instantly.

That medal now hangs in his son’s room.

The boy sometimes holds it and says, “Daddy ran far.”

He doesn’t yet understand what 26.2 miles looks like.

But he understands love when he sees it.

And one day, he will understand that his father didn’t just run a marathon.

He carried an entire community across the finish line with him.