Clarence Thomas Accuses Racially Drawn Voting Districts of Bias — Could VRA Protections Be Overturned?

The Supreme Court’s halls hummed with tension as oral arguments intensified in Louisiana v. Callais, the high-stakes case asking whether race-based congressional districts under the Voting Rights Act remain lawful. In one of the sharpest moments of the day, Justice Clarence Thomas probed the constitutional foundation of such maps, pressing whether they would even exist if states were forbidden from considering race. His questions signaled that he may be ready to strip away protections deemed essential for minority representation — and in doing so, could reshape the balance in Congress itself.

Thomas asked pointedly: “Would the maps that Louisiana have currently be used if they were not forced to consider race?” His line of questioning echoed a core conservative concern that districts drawn with race at the forefront run contrary to the Equal Protection Clause. The suggestion: that voters should never be sorted by racial categories, even when intended to remedy past discrimination. His approach lays bare a clash over whether race-conscious districting is still a viable exercise of congressional authority — or an unconstitutional anachronism.

For years, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act has empowered courts to require majority-minority districts when minority voting strength is diluted. But Thomas’s interrogation strikes at the heart of that premise. If the Supreme Court sides with his framing, states could no longer justify race-based maps simply by reference to demographic fairness or historical inequity. The result could be the unraveling of minority districts nationwide — and with them, the political representation they enable.

Observers watching the session said Thomas’s tone was unmistakable. He seemed eager not just to argue about a single district, but to question the legitimacy of the law that supports it. His ready skepticism of race-based remedies suggests a path to rulings far beyond Louisiana — a turning point in how American democracy manages race, representation, and equality.

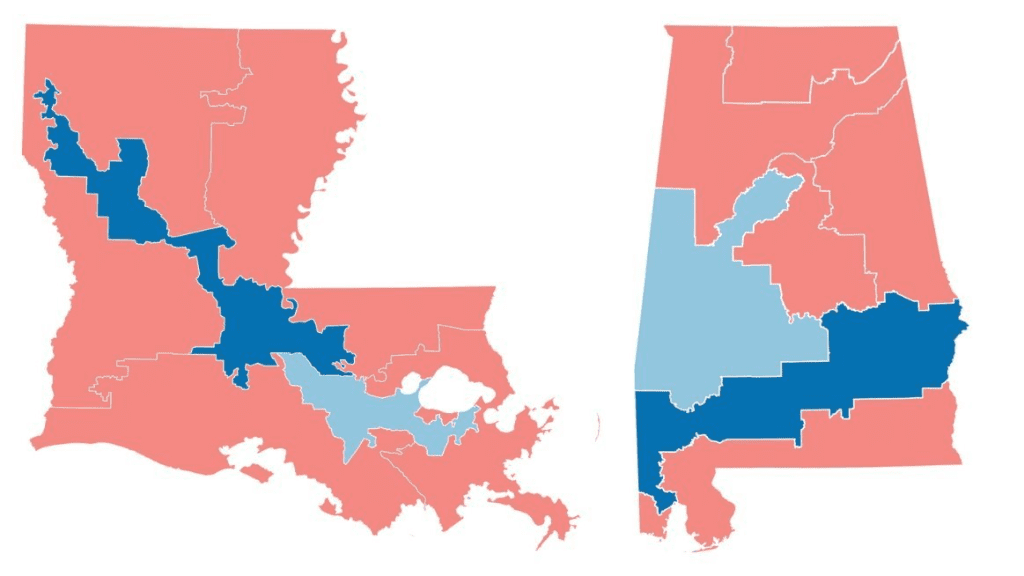

And make no mistake: the stakes are boiling over. Legal analysts, redistricting experts, and political strategists alike have warned that a ruling against race-based mapping could cost Democrats as many as 19 House seats, especially in Southern states like Louisiana and Alabama. These minority districts often skew Democratic; eliminating their legal underpinning would hand the Republicans fresh leverage in the next rounds of redrawing maps and controlling swing state lines.

Yet even as Thomas’s posture drew attention, justices pressed both sides on fine constitutional balance. Others asked whether some race considerations remain permissible under tight constraints, especially where entrenched segregation, voting discrimination, or geographical clustering make purely race-neutral maps distort minority voice. Supporters of Section 2 maintain it is a rightful enforcement tool — a legislative response grounded in history and constitutional intent to correct denial of voting rights.

Louisiana itself has changed tactics. Once defending its remedial map, the state now argues race-based districting itself violates the Constitution — even when used to comply with the Voting Rights Act. It contends that forced reliance on racial categories undermines local control and equal protection. This pivot aligns with Thomas’s push and signals that the case is less about one district and more about the future of congressional mapmaking.

That turning point was foreshadowed in earlier rulings — notably Students for Fair Admissions, which struck down race-based affirmative action in education, and Allen v. Milligan, which upheld minority districting in Alabama but left open room for nuance. Thomas’s questions suggest he may push justices toward a stricter colorblind doctrine — a constitutional standard under which race becomes an off-limits variable in drawing political power.

Whatever the final decision, its ripple effects will be enormous. States awaiting map redraws are primed to act. Minority communities fear a rollback of gains that gave them voting power. And political operatives on all sides are adjusting strategy accordingly. Clarence Thomas’s forceful questions were no mere rhetorical flourish — they may foreshadow a decisive shift in how America judges race, representation, and redistricting.