Epic Showdown: Sheriff Wayne Ivey Rolls Armoured Vehicles Through Drug-House Trouble Zone as Crime Drops in Brevard County

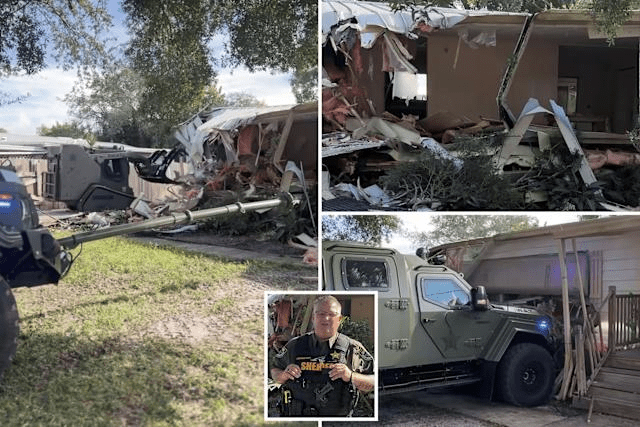

In the heart of Florida’s Space Coast, something bold is changing the landscape of law enforcement. In a dramatic scene caught on video, Brevard County Sheriff Wayne Ivey declared war on one particularly blighted home, announcing pointingly, “Everything we’re doing is legal,” as armored vehicles and excavators moved in to demolish a condemned drug house. That moment reflects a broader push by Ivey’s office: a new “High Intensity Target” unit tasked with razing residential locations that police say feed cycles of drug dealing, violence and despair. The property in question, located on Seneca Drive in Melbourne, was reportedly flagged after numerous service calls, complaints and arrests.

Sheriff Ivey, appearing in a Facebook-posted video, didn’t hide his fire. “We’re gonna tear this piece of crap down,” he said, addressing residents and would-be criminals alike in blunt language. The video quickly went viral, amassing over 100,000 views on social media, as neighbors watched the house crumple in real time. It wasn’t the first. This wrecking-ball moment came just weeks after another demolition under the same unit’s operation. The initiative, known as the “S.H.I.T.” list—or Sheriff’s High Intensity Target list—identifies properties that consistently generate criminal activity and law-enforcement responses.

For a county where many families say fear and fatigue have set in, the force-forward message resonated. Residents in the surrounding area of Seneca Drive described long-standing reports of shooting, drug deals, unmanageable tenants and neighbours who lived in a kind of open war zone. With deputies and community partners alike pointing to the address as a source of ruin, the sheriff’s move carried symbolic and real weight. And the numbers are telling. Brevard County’s violent crime rate fell roughly 12 % between 2023 and 2024 according to state data, bolstered by proactive enforcement efforts.

However, the strategy raises questions. The property-destruction approach relies on the innocence of bystanders not being compromised, strict condemnation procedures, and the public perception of due process being followed. Critics have asked: when does law-enforcement determination become overreach? The sheriff’s office states it is using established condemnation laws, pointing to legal review before taking down structures. In the Seneca Drive case, Ivey told neighbors that multiple attempts at eviction, warnings, inspections and arrests had already failed, leaving demolition as the final measure.

In a broader sense, the move fits into the national shift toward law-and-order messaging, and aligns with voices that support tough crime-fighting policies—echoing a landscape where public safety concerns and conservative governance see renewed focus. Sheriff Ivey’s approach taps into that mood. In Florida, where conservative leadership is strong and voters tend to favour firm responses over leniency, the spectacle of armored vehicles flattening a condemned drug house sends a clear signal: repeat offenders and “nuisance properties” will no longer be tolerated.

Neighbors who have lived with the pain of this particular property reported a sudden change in tone after the action. One resident noted that “calls for service dropped” and that the sight of demolition sparked hope. The sheriff’s video, set to heavy-metal music, opened with Ivey saying: “There’s nothing worse than having a bad neighbour – except a bad neighbour that’s a criminal and trashes up the neighbourhood and puts in a flop-house and meth-ville.” The bold language is part theatre, but the outcome appears concrete: fewer problems, fewer reports, and a restored sense of safety in the community.

The effort also reflects the idea that property rights can be leveraged not just by criminal landlords but by civic authorities to push back when repeated law-enforcement resources are consumed by the same site. By designating addresses under the HIT unit, the sheriff’s office effectively turns those properties into targets for asset forfeiture, condemnation and demolition. While traditional policing focuses on individuals who violate laws, this strategy addresses the place itself—the infrastructure of crime.

Law-enforcement experts note that tactics like these were once confined to large cities tackling drug-infested blocks; seeing this wrapping into a suburban-county context like Brevard suggests an extension of “problem-property policing” into new terrain. It raises ethical and policy questions: how many homes will be condemned? Will residents and property owners get adequate process? Is demolition always necessary, or could rehabilitation and increased monitoring suffice? The sheriff’s office maintains that moving sooner than later prevents cycles of violence and costlier interventions later.

A key component flagged by Ivey is transparency and public notification. The sheriff’s department post on Facebook identified the address, warned residents publicly, and invited community reporting. That approach blends media tactics with enforcement strategy. The transparency serves multiple purposes—it signals accountability, deters impending offenders, and builds public confidence. Indeed, the reception on social media was immediate: praise from some for showing action, scepticism from others who called for detail about legal permits.

Meanwhile, the sheriff has linked the initiative directly to his philosophy that government must prefer action over excuse. In comments around the bust of a convicted felon selling fentanyl and meth, Ivey wrote: “On Halloween or any day for that matter, there is nothing scarier than a drug dealer.” The same urgency shapes his demolition strategy—shifting from reactive arrests to preventative structural removal, which supporters say is precisely what high-crime localities need after decades of failed tolerance.

Although the strategy has gained attention for its spectacle, Ivey insists the objective is practical: restore neighbourhoods, reduce repeat calls, and restore hope to residents. He and his deputies have pointed to a measurable drop in service calls from targeted properties and fewer arrests at those addresses after they’ve been condemned or demolished. In the recent case, local media reported that the Seneca Drive address generated dozens of responses over months before intervention.

Yet the approach is not without risk or controversy. Some civil-liberties advocates warn that aggressive condemnation could sweep up innocent tenants or lead to displacement without sufficient legal representation. Each demolition must navigate county judging, property valuation issues and legal notice. Ivey’s office maintains that in every case they follow the statutory process, even if they leverage public drama to signal resolve. The balance of firm enforcement and fairness remains under watch.

In Florida’s current political climate—where sharp-edged rhetoric on crime, drugs and property rights dominate—the Brevard strategy fits into a broader narrative. It appeals to voters who say they’ve lost faith in conventional policing, and who want more decisive measures. For Sheriff Ivey, the timing is significant: with national attention on law enforcement and local governments under pressure to show results, his HIT unit offers a tangible demonstration of action.

For families in Brevard County, the effect is emotional as much as operational. One mother whose child attends a school near the targeted home said: “We used to pass that house on the bus and feel uneasy. Now it’s gone. I can breathe again.” That shift from fear to relief speaks to the broader promise of this initiative: reclaiming neighbourhoods from the grip of chronic crime. In a society where many programs feel symbolic, the demolition offers hard proof.

What happens next is critical. Sheriff Ivey has said the program will continue—more homes on the “list,” more scrutiny, more public countdowns to intervention. As the social media videos roll out, the message is clear: “Don’t mess with Brevard.” Officials said future homes will face the same fate if they become hubs of criminal activity. Whether this will lead to lasting reduction in crime or cause contentious legal fights remains to be seen.

What can’t be denied is the transformation visible on one street in Melbourne, Florida. An address once synonymous with meth, violence and fear is now rubble. For those who live in that neighbourhood, the change offers something many communities crave: safety, quiet, a chance to rebuild. For law enforcement, it marks a new style of policing—one that treats places as partners in crime rather than just suspects. And for policymakers, it may offer a template for neighbourhood-renewal in hard-hit counties across the country.

Indeed, in an era when the national conversation around crime often feels stalled or ideological, evidence of reduction is powerful. Brevard’s roughly 12 % drop in violent crime (per state law-enforcement data) during 2023-24 provides a backdrop to the demolition effort—not proof by itself, but indication that aggressive tactics, when executed properly, might make a difference.

This story, of property destruction as peace restoration, invites deeper reflection. Does tearing down homes solve root causes? Or does it simply clear visible symptoms while many houses still operate. Sheriff Ivey argues the point: some places must be taken off the map for good because they cannot be redeemed. He calls them “trashville,” “methville,” and “flop-houses.” His language may be sharp, his approach bold, but his goal is heartfelt: “My community, my children, my neighbours deserve better.”

In sum, what unfolded on the streets of Brevard County is more than a flashy video. It is a case study of how local enforcement is changing tactics, how communities weary of chronic nuisance properties find new hope, and how bold leadership can spark a ripple of action. For the people who live there, fewer sirens at night may mean one more year where kids can play outside and families can feel safe. For law-makers and sheriffs across America, the question becomes: will they follow, or watch from the sidelines as others take the wrecking ball?