Ginny Burton Was Once a Lifelong Drug Addict with 17 Felony Convictions — Now She’s a University of Washington Honors Graduate Fighting for Justice

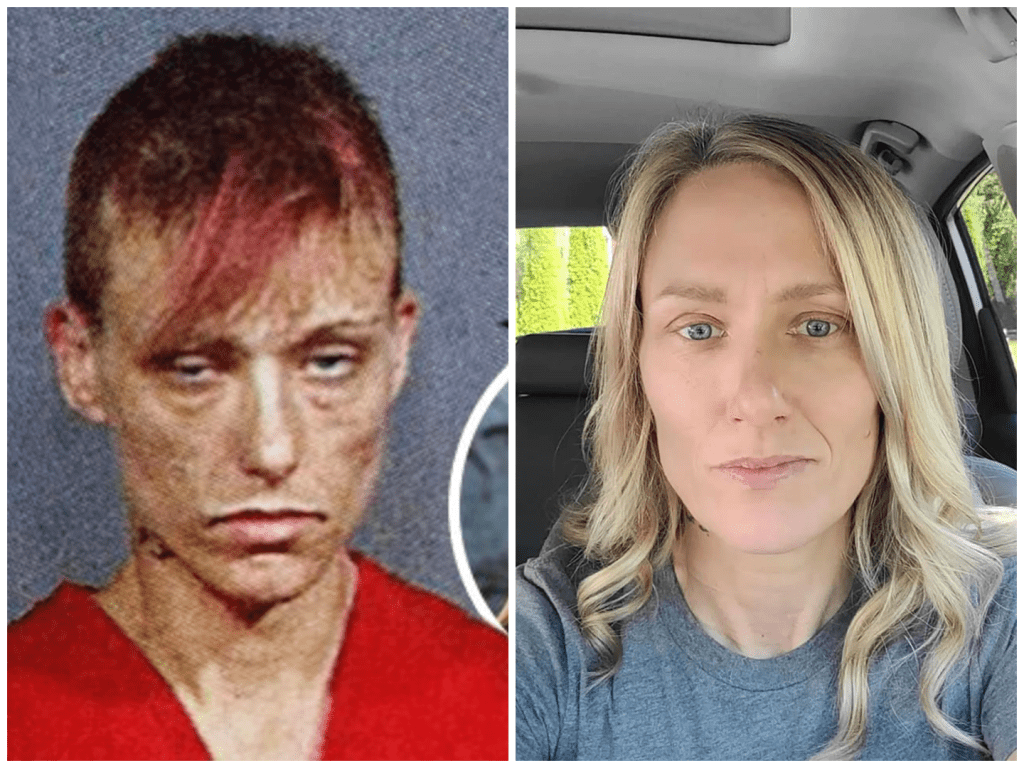

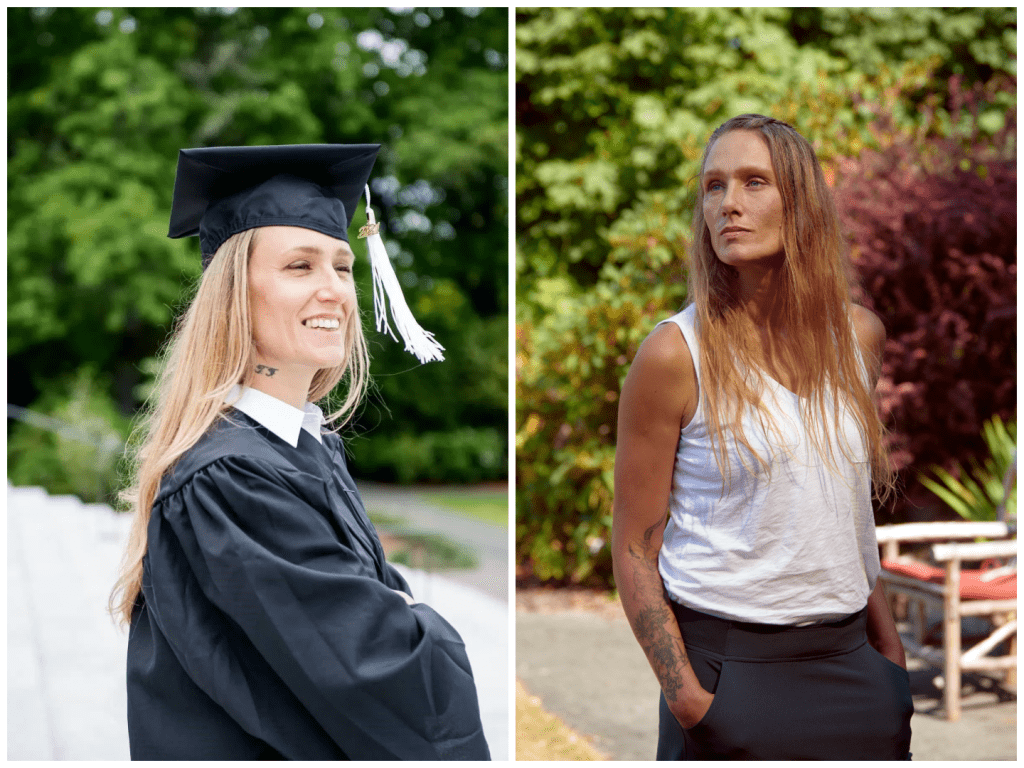

Ginny Burton’s journey is the kind of story that feels mythical — except it’s completely real. I first saw a photo of her before-and-after side by side and thought somehow the captions were swapped. On the left: a mug shot from 2005, eyes hollow, body gaunt, wearing jail stripes after years of meth, crack, and heroin addiction. On the right: graduation day at the University of Washington, beaming in cap and gown at age 48, degree in political science in hand, honored with scholarships and academic awards. The transformation is staggering — but the truth behind it is human, raw, and utterly inspiring.

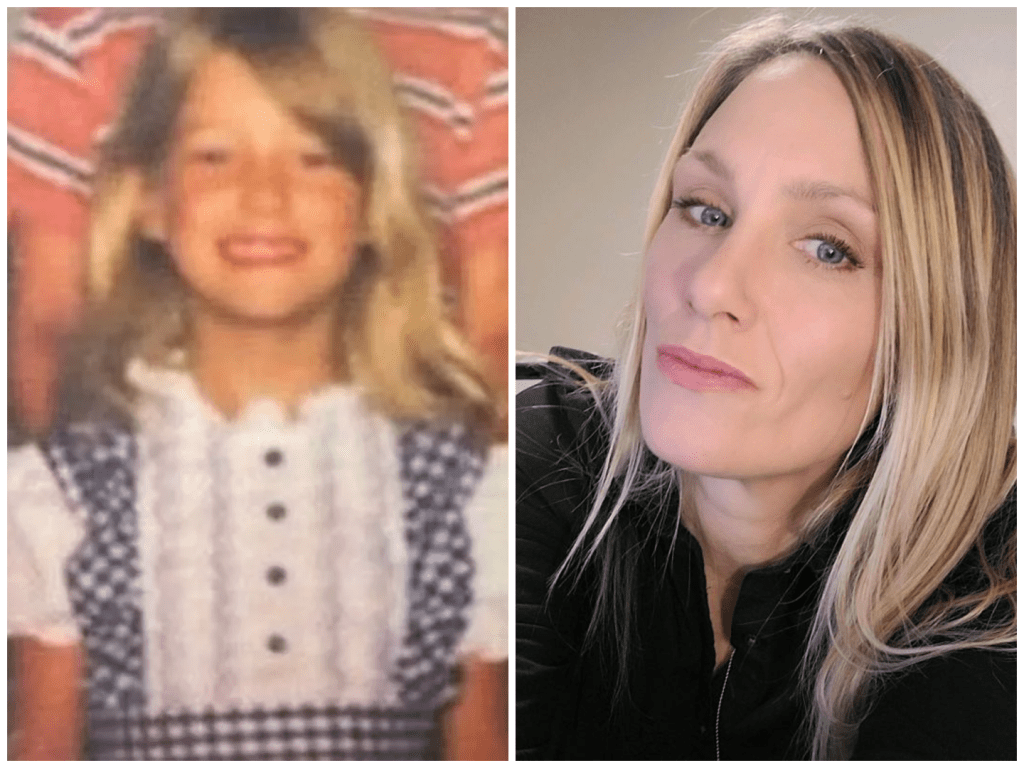

Burton’s childhood was violent and unstable enough to shatter most souls. Born in Tacoma in 1972, her mother was a drug dealer and addict; her father was behind bars by the time she was four. Ginny started smoking marijuana at age six, moving to meth by twelve and heroin by twenty-one. Her teens were marked by trauma, overdose attempts, theft, abuse, and ultimately, incarceration. She carried seventeen felony convictions — armed robbery, assault, identity theft, drug charges — and a mind numbed by years of chemical dependency. She spent most of her twenties locked in and out of prison. In 2012 she hit rock bottom again. This time, the jail cell became an unlikely turning point. With no bail and no option but to detox in custody, she wrote that moment off not as defeat but as a final chance. She embraced drug court, completed counseling, and began the hard, painful business of rebuilding.

Once released, Burton didn’t slip back. Instead she pushed forward into community work. She found herself serving at the Lazarus Day Center, a shelter run by Catholic Community Services. She listened to others’ stories, recognized herself in their pain, and built trust through absolute honesty. In those shadows she discovered the strength to change. A spark of hope became a steady flame.

By her mid-forties she enrolled in community college — a room full of students decades younger than her. She struggled at first but soon realized she loved learning. The rigorous reading, the unfamiliar terms in political science, the culture shock — it made her feel alive again. She earned merit scholarships, then transferred to the University of Washington on a Martin Honor Scholarship, eventually being named a Truman Scholar for Washington state. She graduated with honors at 48, a formal degree in political science.

In interviews, Burton reflects on her past not with regret, but gratitude for the lessons that unveiled her deepest purpose. She said she doesn’t blame where she came from but sees it as material for transformation. She credits the criminal justice system — specifically, drug court — for giving her the structure to change. Without incarceration, she says, she might not have ever stopped. What she found in prison was not shame, but clarity.

Today Ginny is a mentor, speaker, and advocate for reform — focusing on trauma-informed incarceration, recovery programs, and re-entry support. She created a program called O‑UT (Overhaul–Unrelenting Transfiguration), designed to guide others out of cycles of addiction, crime, and homelessness. She lives in Rochester, Washington, with her husband Chris, himself clean and formerly incarcerated, and one of her priorities is breaking generational trauma.

But what strikes me most is her insistence on authenticity. Burton often posts that the person in that mug shot and the person in that graduation photo are the same woman — just living very different chapters. One taught her shame. The other taught her self-love. Every day she reframes her self-talk to affirm that she is deserving of grace. She shares glimpses of her hikes, scholarship wins, moments with family, and the occasional hard memory. Through it all, she remains committed to being seen — not as a statistic, but as proof that change is possible.

In a world where addiction and incarceration too often mean invisibility, Burton has chosen visibility as resistance. She shows up wherever she’s needed — advocating at panel discussions, mentoring women in sobriety, pushing for criminal justice reform based on lived experience. She educates through empathy, not judgment.

Her story is not just about redemption — it’s about reclaiming identity. She once told a local reporter that if she keeps breathing, she can do anything she sets her mind to. She repeats that mantra as a daily practice, because sometimes believing in possibility is the greatest act of courage.

Graduating at 48 with honors, scholarship awards, and plans for further graduate study is the kind of milestone we usually reserve for young dreamers. But Burton shatters that timeline. She shows that life paths can circle back, restart, and bloom again, even when hope seems gone. To look at those two photos of her is to see heartbreak and triumph, shame and grace, brokenness and brilliance — all in the same face.

When I think about her journey, I’m reminded that the hardest roads often lead to the most beautiful views. Ginny Burton didn’t just survive addiction, prison, and shame — she transformed them into a platform for service and healing. Her success is not about celebrating the degree, but celebrating the person she became along the way.

So if you scroll past her story, let it stick today: no soul is irredeemable. No past is final. And no age is too late to rebuild. Because Ginny lives that every single day.