California Governor Gavin Newsom Pledges Climate “Partnership” With Nigeria Amid Ongoing Christian Genocide — Critics Furious

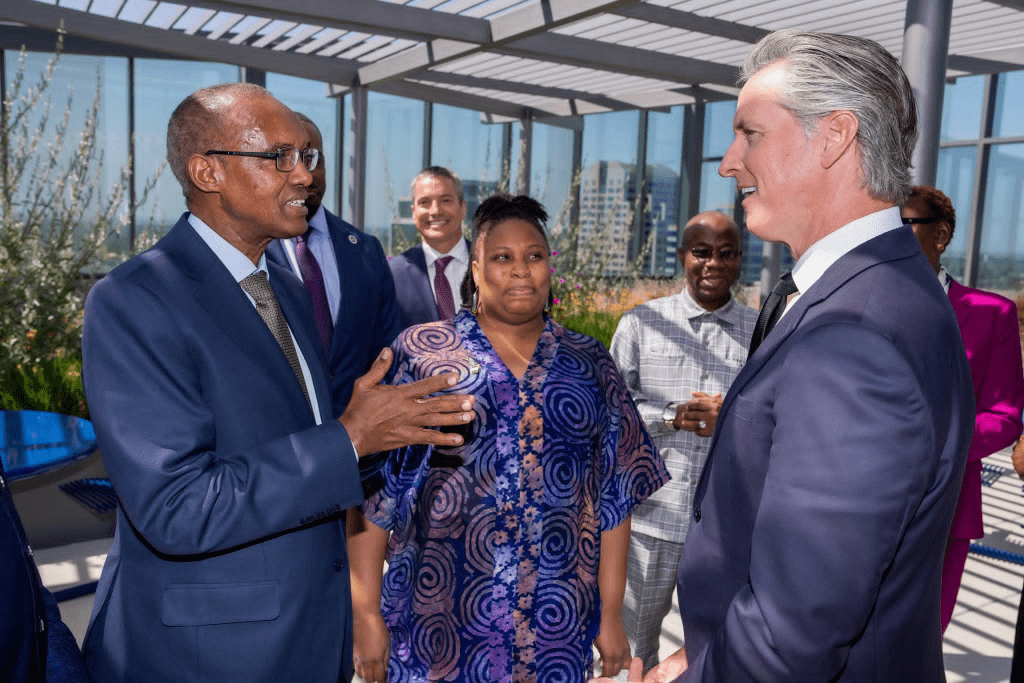

In the rainforest-fringed halls of COP30 in Belém, Brazil, Gavin Newsom stood before the global spotlight as the lone senior U.S. delegate while Washington abstained. He signed an expansive memorandum of understanding with Nigeria centered on climate adaptation, sustainable transport, green ports and low-carbon technology. The announcement made headlines. But a deep unease rippled beneath the surface. For while Newsom talked urban mobility and zero-emission fuel, Nigeria is simultaneously ranked among the world’s worst places for Christian persecution — more than 5,000 Christians were killed in 2024 alone. The contrast sparked instant backlash: why was climate-action diplomacy receiving attention when bodies were piling up in Nigeria’s Middle Belt?

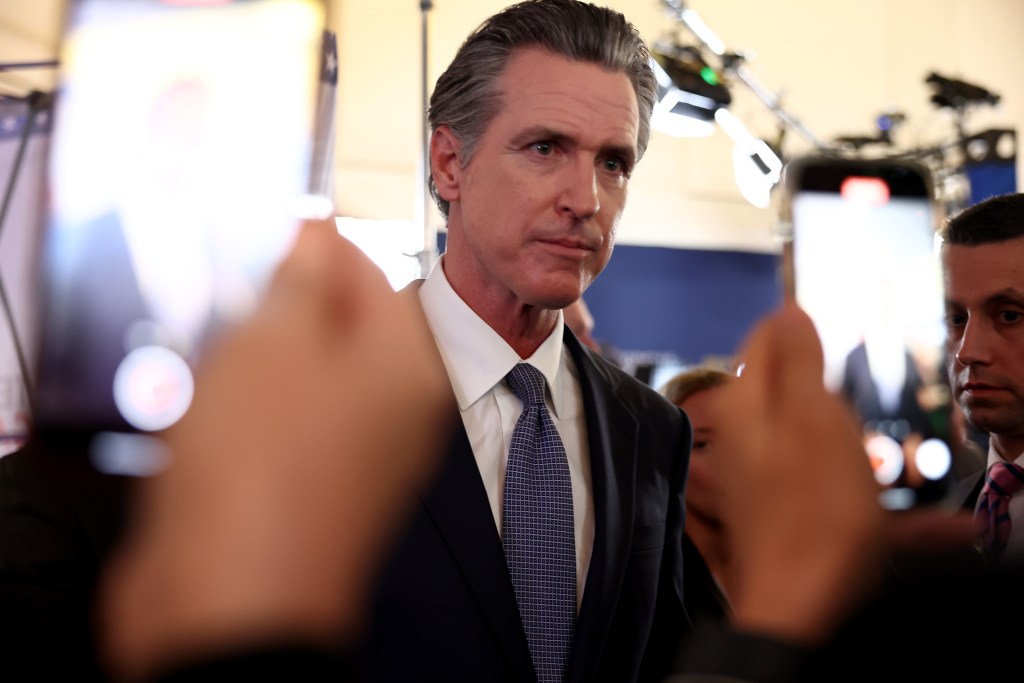

The California governor, widely seen as a future presidential contender, framed his participation as proof that U.S. leadership does not have to come from Washington. “The reason I’m here is in the absence of leadership coming from the United States,” he said. He touted California’s record — greenhouse gas emissions down 21 percent since 2000, economy booming, battery storage up 1,944 percent since he took office. At the press event he joined a side-agreement with Nigeria on sustainable urban transport, methane-reduction policies, air-quality monitoring and academic exchange. An official California press release noted: “California is honored to join hands with Nigeria — a powerhouse of trade, technology and innovation — to build a cleaner, more connected future.”

Yet the relevant context cannot be ignored. Nigeria, the most populous nation in Africa, features on the Open Doors 2025 World Watch List as a Top-10 country for Christian persecution. Islamist militants linked to Boko Haram and the Fulani insurgency killed more than 5,000 Christians in 2024. Entire villages were razed. Churches burned. Christians displaced. In the face of that crisis, many critics say Newsom’s climate deal reads tone-deaf at best. One senior human-rights advocate asked: “When children are blown up in church services, where is the urgency of U.S. diplomacy?”

The deal also raises questions about priorities. On one hand, climate diplomacy and clean-tech investment are vital global challenges. On the other, Nigeria’s frontline war with extremist violence should demand immediate attention. Newsom’s move reflects the tension between big-picture global strategic engagement and on-the-ground human suffering. His supporters tout the partnership’s long-term potential: green jobs, technology transfer, trade linkages. They argue that climate adaptation in Africa will help create stability, reduce conflict drivers and deliver innovation. Detractors counter: there is no sustainability without peace, and until Christians and other minorities can worship without fear, climate-action diplomacy is circular.

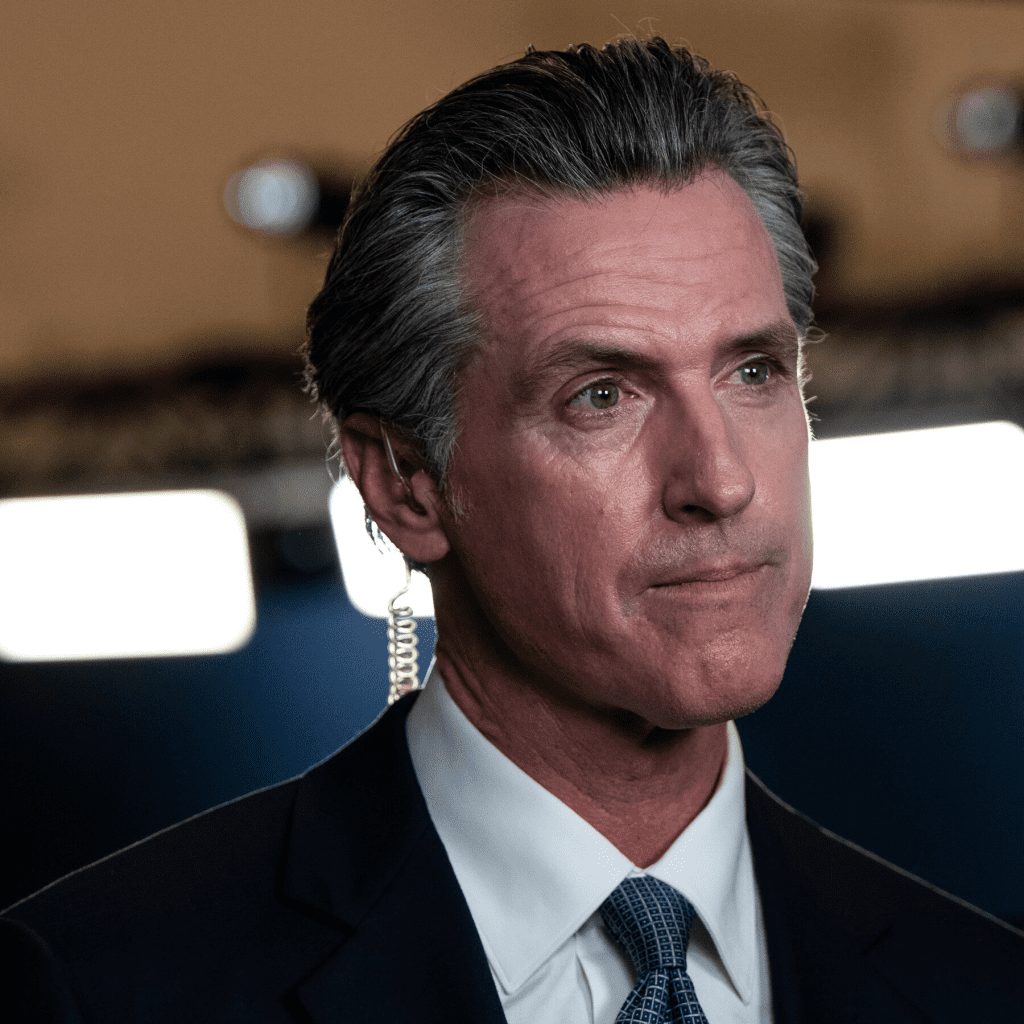

From a political perspective, Newsom’s gambit is not purely altruistic. At COP30 he is already being cast as a national alternative to the federal absence. He draws contrast with Donald Trump and other federal actors for skipping the summit. This positioning may fuel his 2028 ambitions. But this high-stakes global footprint invites scrutiny — including of whether his agenda aligns with rhythm of voter concerns beyond California. The migration of American climate diplomacy from Washington to Sacramento is emblematic of changing power geometry, yet the reaction to this Nigeria deal signals that global symbolism may not always translate to domestic consensus.

Inside the deal, specifics matter: California and Nigeria will work on “sustainable urban transportation, green ports, low-carbon transportation fuels, methane detection and abatement, greenhouse-gas emissions and air-quality, and academic exchange.” The release named Nigeria’s new Presidential Climate Council and its carbon-market framework as entry points. The agreement is five years in length, covering research, workforce training, and infrastructure investment. The state emphasized “jobs, technology, mobility and climate.” In the COP press briefing, Newsom said: “The world can count on California to keep leading and innovating as we build the future with cleaner air, good jobs and economic growth.”

Yet, remarkably, the agreement did not, at least publicly, prioritize religious-freedom protections or humanitarian corridors for persecuted minorities. In Nigeria’s particular case the climate adaptation pact diverges markedly from the urgent plea of Christian communities who continue to flee attacks. The perception of misplaced focus is both symbolic and tactical. In console rooms of human-rights advocates, analysts note that climate diplomacy should not be zero-sum, but in this case the optics feel dissonant.

From Lagos to Kaduna, Nigeria faces intertwined challenges: decades of insurgency, banditry, kidnappings, church bombings and internal displacement. Experts caution that climate vulnerability contributes to conflict — land degradation, cattle-herder encroachment, resource stress. In that light California’s climate initiative can be seen as relevant. But the sequencing, strategy and public framing become crucial. A scholar of African conflict told this outlet: “Climate action won’t solve genocide. Unless the military, state capacity and rule-of-law are strengthened, any infrastructure deal is scaffolded on chaos.”

Newsom’s team argues they are aware of the context. In their statement they pointed to Nigeria’s Presidential Climate Council, and described the partnership as part of a broader shift in U.S. states engaging globally. The California executive summary noted that state-level diplomacy can fill the vacuum when national leadership retreats. The same summaries point to California’s ambition to export its cap-and-invest program, clean-technology economy and climate resilience credentials to the world stage.

Still, the criticisms persist. A spokesperson for the victim-advocacy NGO said: “There’s equal urgency in Nigeria to protect believers being slaughtered as there is to invest in low-carbon transport. The silence on the former is deafening.” Others point out that the U.S. federal government remains the primary entry point for foreign-policy sanctions, international aid and defense cooperation. California can sign MOUs — but it lacks the diplomatic arsenal of the State Department or Pentagon. Critics suggest symbolic deals risk substituting for substantive policy engagement.

Meanwhile, inside COP30’s packed schedule, Newsom’s Nigerian agreement is but one among many. Smaller jurisdictions, municipalities and states from Europe to Africa are signing bilateral climate pacts. Nigeria is present in the global field—one of the countries with large delegate numbers. But as the conference grapples with adaptation finance, loss and damage, and the global emissions stocktake, underlying human-security issues remain acute. COP30 dispatches highlight that while technical negotiations proceed, absence of major national delegations—such as the U.S. federal one—shifts power to subnational actors.

For the residents of California, the deal also raises questions of domestic cost-benefit. Climate allies praise the export of California clean-tech. But critics within the state ask: does this global footprint justify the price tag and political risk? If Newsom is building a national brand, are Californian taxpayers inadvertently funding a global campaign? And if the Lagos-Nigeria axis diverges from American domestic voters’ concerns—such as border security, inflation, crime—will the strategy produce returns?

One Washington analyst summarised the moment: “It’s both a golden marketing moment and a trap. States that take on global diplomacy must face the scrutiny of doing diplomacy with a capital-D, rather than merely domestic policy with a global backdrop.” In Newsom’s case, the spotlight is there, but so is the lens.

For Nigeria, the benefits of a partnership with California may include transfer of clean-tech expertise, investment in green ports and sustainable urban transport, and aligned research and academic exchange. Such moves could yield careers for Nigerian youth, reduced emissions, improved infrastructure. But for Nigerians who endure church bombings, displacement and violent raids, the relevance of greenhouse-gas reduction feels remote by comparison. The moral calculus is unmistakable: when one crisis burns now and another threatens later, what should come first?

Ultimately, the story of California’s climate deal with Nigeria is a story of ambition and contradiction. It reveals how modern diplomacy is being reframed—where U.S. states assert international leadership, where climate action becomes geopolitical branding, where human-rights concerns remain tangential in high-tech policy talks. It asks readers to consider balance between long-term planetary goals and immediate human suffering. It challenges the notion of who gets to speak for America abroad, and how priorities are set when multiple crises collide.

Whether this partnership will stand the test of time depends on delivery. Will California and Nigeria meet concrete milestones? Will Nigerians see jobs, cleaner air, and safer cities? Will Christians in Nigeria gain secure places of worship free from fear? Will Newsom’s presidential aspirations survive scrutiny of global bridging without domestic roots? The answers remain to be seen. But for now, a deal was signed, a stage was set, and the world watched—from Brazil, from Africa, from California and beyond.