Trump’s Reversal Leaves 353,000 Families Facing Uncertain Futures

In the bustling corridors of a South Florida strip mall, where the scent of plantains sizzles from a nearby bodega and reggaeton pulses from open car windows, Marie Jean-Baptiste paused mid-shift at her nail salon on November 26, 2025, her phone buzzing with a notification that turned her world upside down. At 48, the Haitian immigrant had built a quiet life in Miami since fleeing Port-au-Prince’s chaos in 2011, her Temporary Protected Status (TPS) a fragile shield allowing her to work, send remittances to her aging parents, and save for her 16-year-old son’s college dreams. The Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Register notice—announcing the termination of TPS for Haiti effective February 3, 2026—hit like a gut punch, stripping protections for 353,000 people like her who have called America home amid their island’s unending turmoil. “I’ve paid taxes, voted, raised my boy here—what now? Send us back to bullets?” Jean-Baptiste asked, her voice trembling as she showed the alert to a coworker, tears smudging her apron. For families scattered from Boston to Seattle, the decision evokes a profound ache—a sudden unraveling of roots planted in soil they helped till, forcing choices between the safety they’ve known and the dangers awaiting across the sea.

Haiti’s TPS designation, a humanitarian pause on deportation granted in 2010 after a catastrophic earthquake that killed over 200,000 and left 1.5 million homeless, has been a lifeline extended through waves of calamity. Renewed under Presidents Bush, Obama, Trump (once, in 2017), and Biden—who stretched it to August 2026 in June 2024 citing rampant gang violence and political collapse—the program shielded migrants from return to a nation where 5.4 million face acute hunger and assassinations topple leaders like Jovenel Moïse in 2021. By November 2025, it enveloped 353,000 beneficiaries, per DHS figures, many arriving post-earthquake or fleeing subsequent hurricanes like Matthew in 2016, their contributions woven into America’s fabric—from construction crews rebuilding Florida after Irma to nurses staffing COVID wards in New York. Jean-Baptiste, who crossed the border legally on a visitor visa before qualifying for TPS, embodies that integration: Her salon employs three Haitian women, and she volunteers at a local church teaching Creole to kids of mixed heritage. “This isn’t charity—it’s partnership. We’ve earned our place,” she said, her hands—calloused from years of manicures—gesturing to photos of her son in cap and gown, a milestone TPS made possible.

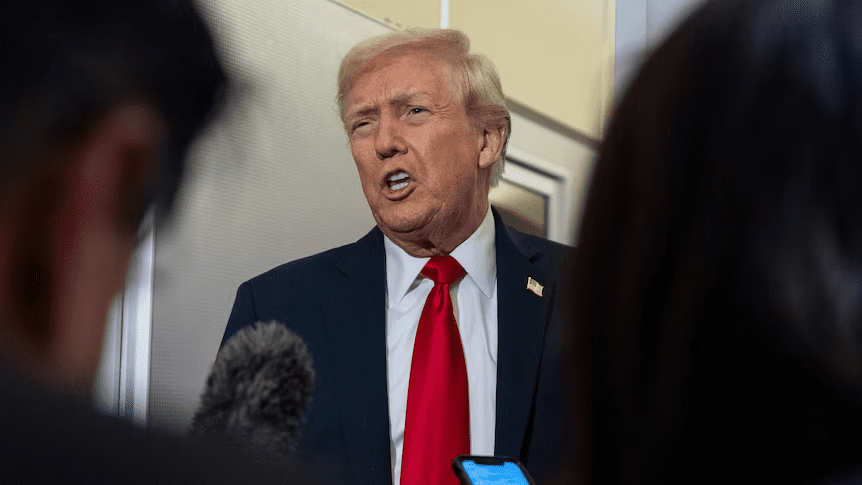

The Trump administration’s reversal, announced via the Federal Register and signed off by Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, marks a sharp pivot from Biden’s extensions, prioritizing enforcement in a nation where border encounters dropped 40 percent since January 2025 under stricter asylum rules. Noem, in a November 26 statement from Sioux Falls, framed it as “restoring integrity to our immigration system,” citing Haiti’s stabilized elections and reduced violence as grounds for termination, despite UN reports of 4,000 deaths from gang clashes in 2025 alone. “Haiti no longer meets the statutory criteria for TPS—it’s time for self-reliance and orderly migration,” she said, her words a nod to Trump’s campaign pledges to end “abuses” of the program, which he curtailed for 60,000 Haitians in his first term before courts intervened. The decision affects all 353,000, including 200,000 in Florida alone, where Haitian communities in Little Haiti and Broward County form vibrant hubs of culture and commerce. For Jean-Baptiste, the timeline—180 days to depart or seek alternatives like asylum renewal—feels like a countdown to chaos. “My son’s high school graduation is in June—do we pack now, or fight till the end?” she wondered, her salon chair empty as she scrolled legal aid sites, the hum of her clippers silenced by worry.

The human stakes, far beyond statistics, unfold in living rooms and workplaces where TPS holders have woven their lives into America’s daily rhythm. Take the Duval family in Springfield, Massachusetts, where 52-year-old carpenter Jacques, who arrived after the 2010 quake, has raised three U.S.-born children while framing homes for Habitat for Humanity. TPS let him work legally, buy a modest ranch house, and coach soccer for his son’s team—milestones that now teeter on asylum applications with 18-month backlogs. “I fixed roofs after Sandy—now, who’s fixing mine?” Jacques asked during a community forum in a Haitian Baptist church, his voice steady but eyes distant as 150 attendees nodded, sharing tales of TPS as the thread holding dreams intact. In Houston, 39-year-old teacher Marie-Louise Pierre, who fled gang extortion in Cap-Haïtien, tutors English to her neighbors’ kids after school, her $45,000 salary stretched thin by $1,800 rents but buoyed by TPS stability. “My students are Haitian-American—they ask if I’ll be here for graduation. What do I say?” she confided to a caseworker, her chalk-dusted hands folding a tissue as the news sank in.

Public reaction, from Miami’s Little Haiti to Capitol Hill hearing rooms, forms a tapestry of fear, fight, and faint hope. In Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis vowed state resources for renewals but warned of federal deportations, Haitian-American leaders like Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz rallied 5,000 at a Bayfront Park vigil on November 27, voices rising in “Sweet Caroline” blended with Creole hymns. “These are our neighbors, our workforce—ending TPS rips families apart,” Wasserman Schultz said, her arm around Jean-Baptiste, whose salon donated services for the event. Advocacy groups like the Haitian Bridge Alliance filed emergency suits in federal court, arguing Haiti’s 2025 instability— with gangs controlling 80 percent of Port-au-Prince per UN estimates—renders return unsafe, citing the Immigration and Nationality Act’s “extraordinary circumstances” clause. “TPS saved lives then; it must now,” said attorney Michelle Lapointe, whose firm represents 2,000 clients facing the cutoff, her caseload swelling with frantic calls from nail techs to nurses.

Trump’s team, emphasizing enforcement amid a 50 percent drop in illegal crossings since inauguration, views the termination as fulfillment of promises. Noem, in a Fox News interview on November 27, highlighted Haiti’s “progress” under transitional President Guy Philippe, elected in October 2025 amid violence that killed 1,200. “We’re not heartless—we’re humane, prioritizing American workers and secure borders,” she said, pointing to $500 million in U.S. aid for Haitian elections as evidence of support without open-ended stays. Critics, including Sen. Bob Menendez (D-N.J.), decried it as “cruel theater,” his floor speech invoking his own immigrant roots to argue TPS’s $2 billion economic boost from Haitian labor. Public polls from Monmouth University in late November show 52 percent of Americans favor extension, up from 45 percent in 2024, driven by stories like the Duvals’—families contributing taxes and community service while fearing midnight raids.

As February 3 looms, the cutoff casts long shadows over holidays tinged with uncertainty. Jean-Baptiste plans a family meeting in her salon, surrounded by polishes and posters of Port-au-Prince sunsets, to weigh asylum or voluntary return. “My boy’s American—born here, loves baseball. Do I uproot him for a country I fled?” she ponders, her resolve a mix of fear and fire. For the Duvals in Massachusetts, it’s late-night applications and community fundraisers, Jacques framing a crib for a neighbor’s newborn as a small act of defiance. In this season of gratitude, Haiti’s TPS end reminds that protection is fragile—a thread in the American quilt, pulled tight by policy but held by human hands. As families like Jean-Baptiste’s gather around tables laden with griot and gratitude, their stories call for compassion: Not just borders secured, but hearts welcomed, in a nation ever remaking itself.