After Avoiding Water for Over 60 Years, “World’s Dirtiest Man” Amou Haji Took a Bath for the First Time—and Tragically Died Weeks Later at 94, Leaving Behind a Life That Still Puzzles and Inspires the World

The story of Amou Haji is one of those rare human tales that feels stranger than fiction, and yet somehow deeply poetic. It’s the kind of story that makes you pause, not just out of shock or curiosity, but out of a quiet sense of wonder. Who would choose to live a life without bathing for more than half a century? And what does it mean when that same person finally gives in, takes a bath—and dies just weeks later?

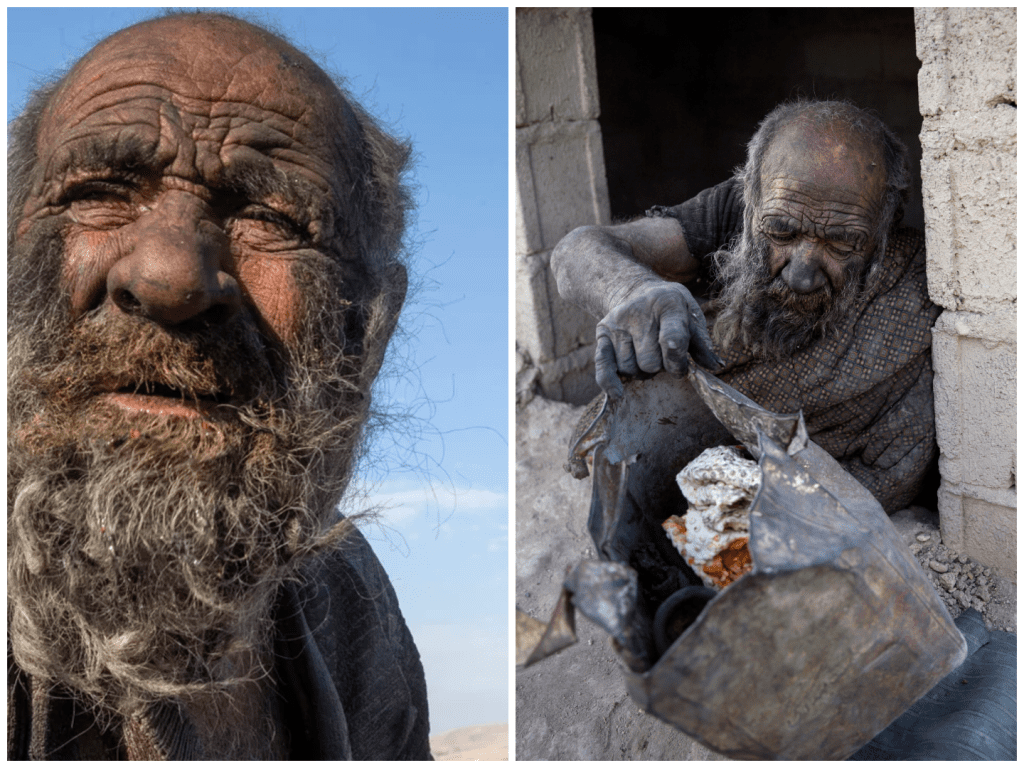

Born in 1928, Amou Haji lived in the village of Dezh Gah, in Iran’s Fars province. For most of his life, he remained largely disconnected from society, choosing a path so unconventional that it earned him international attention and an unforgettable nickname: “the world’s dirtiest man.” It wasn’t a label he chased or a record he aimed to break. It was simply the result of a way of life rooted in fear, trauma, and isolation.

As the story goes, Amou Haji made the decision to stop bathing sometime in his youth. The reason, according to locals and several journalists who had visited him over the years, stemmed from emotional hardship. It’s said that after suffering intense heartbreak and psychological distress, he came to believe that bathing—especially with soap and water—would make him sick. Whether that belief was tied to spiritual superstition or deeply personal fears, he embraced it so thoroughly that it became a cornerstone of his identity.

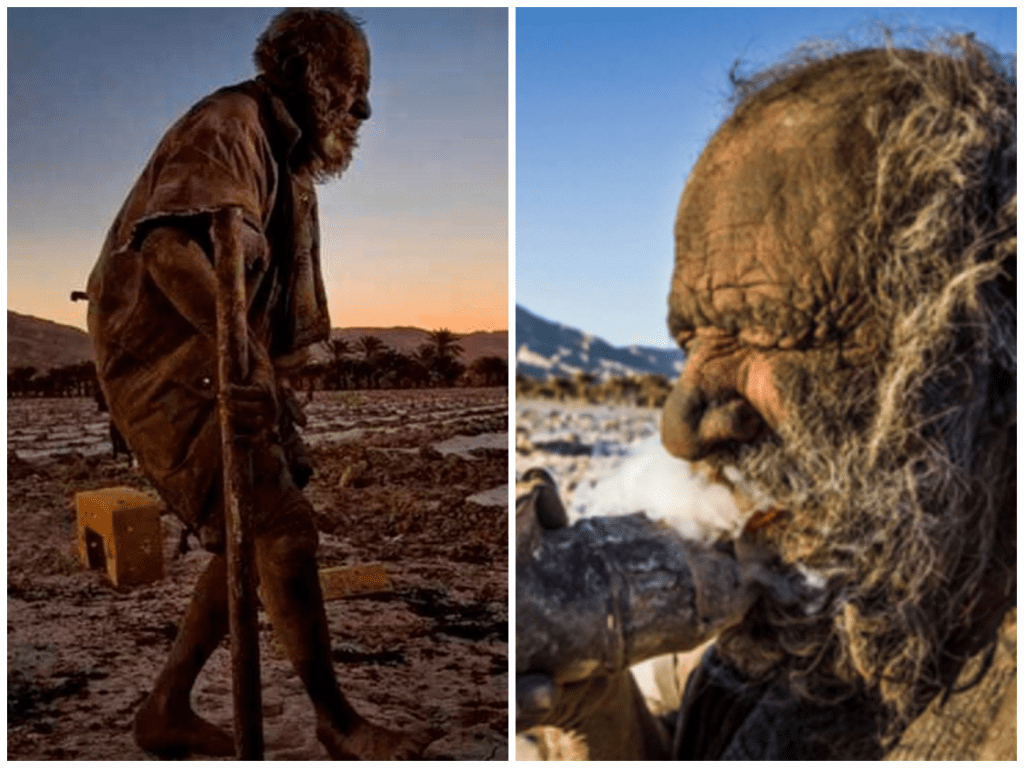

He didn’t just avoid showers. He avoided anything remotely hygienic by modern standards. Amou drank from rusty cans and muddy puddles. He ate roadkill—often preferring the meat of decaying porcupines. He smoked animal feces and burned his hair instead of cutting it. He lived in a cinderblock shack built for him by caring neighbors, who, while often puzzled by his lifestyle, still made efforts to care for him. They would bring him food, check in on his health, and offer help when needed. And despite his rugged lifestyle, he rarely fell ill.

In a way, Amou became something like folklore—more than a man, almost a living legend. In 2013, a short documentary titled “The Strange Life of Amou Haji” captured his way of life and introduced him to a broader audience. While viewers were initially stunned or even amused by the sight of this soot-covered man, what stuck with people was not the shock factor—it was the quiet conviction with which he lived.

He never asked to be famous. But the attention came anyway. His story spread across news outlets and social media, with people calling him “the last man untouched by modern civilization” or even jokingly comparing him to mythical characters. And through it all, Amou remained largely the same. He continued living as he always had—wary of change, wary of water.

But in late 2022, something changed. According to Iranian state news agency IRNA, Amou Haji agreed—perhaps after persistent urging from locals, or maybe due to declining health—to take a bath for the first time in decades. He was 94 years old. The villagers helped him. They didn’t ridicule him or treat it as a spectacle. They gently guided him through the process. And for the first time in more than sixty years, water touched his skin.

Just a few weeks later, Amou passed away peacefully in his home.

The timing of his death stirred immediate reactions online. Some took it as a dark coincidence, others speculated about causality—wondering aloud if bathing had truly contributed to his passing. But most medical experts and observers agree: at 94, Amou had simply reached the natural end of a long life. His body, by that age, was likely already frail. The bath didn’t kill him. But the timing made the story feel almost too surreal to ignore.

His death sparked renewed interest in his life and legacy. People asked questions that went far beyond the bizarre facts. What does it mean to live so far outside the norms of society? What happens to the body and mind when we isolate ourselves so deeply for so long? Was his fear irrational, or was it simply his form of self-preservation? And perhaps most hauntingly—did finally letting go of his deepest fear mark the end of his purpose?

In the modern world, where cleanliness is tied to morality, success, and social acceptance, Amou Haji was a contradiction. He was an outlier who lived in filth and yet outlived most of his peers. He refused the basic routines most of us wouldn’t question—and yet somehow, he survived. For decades. And when he finally gave up that one last piece of control, life seemed to slip from him, as if the fear had been holding him together all along.

Of course, there’s no scientific link between taking a bath and sudden death. But the emotional weight of his story lingers. Maybe it’s because his extreme lifestyle challenges everything we assume about health and longevity. Maybe it’s because we admire someone who dared to be so unapologetically himself—even when that meant becoming a global oddity. Or maybe it’s because Amou Haji reminds us that humans are far more complex than we understand. That trauma can shape us in ways even science can’t fully explain. And that habits, once embedded deep enough, become pillars of survival—no matter how irrational they may seem from the outside.

After his passing, tributes poured in. Some honored his resistance to modernity. Others saw him as a kind of tragic figure—someone who chose solitude to escape pain. But everyone, it seemed, felt something. And that alone speaks volumes.

In a time when the internet moves too fast and stories lose their meaning before the next trend arrives, Amou Haji’s life stopped people in their tracks. Not because he was dirty. But because he was human, raw, and unfiltered in a way few people are anymore.

He didn’t care about headlines. He didn’t care what people thought of him. He didn’t build a brand or seek a platform. He simply lived—and when the time came, he died just as quietly.

Rest in peace, Amou Haji. You were strange, yes. But you were also brave. And in your way, you reminded us all that to be human is not always to be clean, understood, or conventional—but to be exactly who we are, even when the world doesn’t know what to make of it.