New DNA Study Suggests Adolf Hitler Suffered From Kallmann Syndrome, Possibly Explaining His Micropenis and Single Testicle

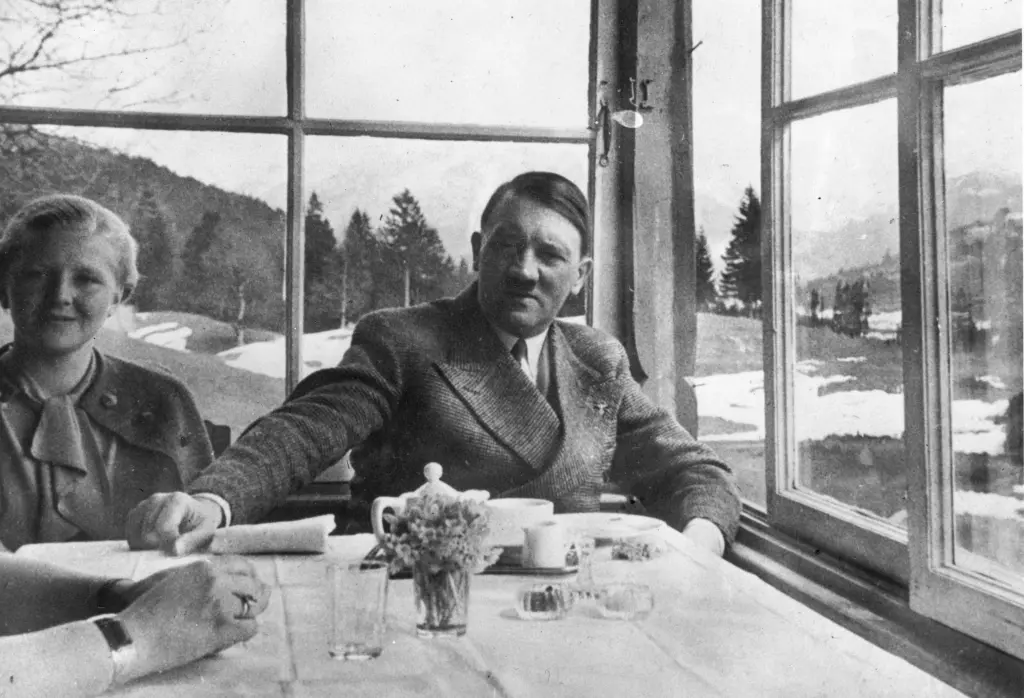

A groundbreaking genetic analysis now suggests that Adolf Hitler, the Nazi dictator whose name is forever etched into history for immense evil, may have endured a rare genetic condition that affected his sexual development and perhaps even aspects of his psychological make-up. According to the team of international scientists behind the film Hitler’s DNA: Blueprint of a Dictator, Hitler likely suffered from Kallmann syndrome, a disorder that results in delayed or absent puberty, underdeveloped sexual organs and a diminished sense of smell. The findings invite fresh reflection on a villain shaped by trauma, physiology and ambition—but they also come with cautionary reminders about what DNA can and cannot explain.

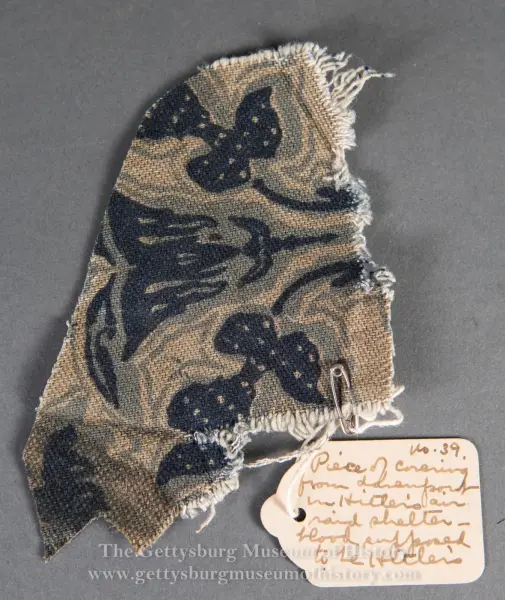

The origins of the study are as dramatic as the results. Researchers obtained a small piece of fabric reportedly cut by a U.S. Army officer from the sofa in Hitler’s bunker—where Hitler died by suicide on April 30, 1945—along with traces of his blood. From that sample, the team led by forensic geneticist Turi King extracted a DNA profile and compared it to known male-line relatives to validate the identity. Their work suggests not only that Hitler had Kallmann syndrome, but also that he had “very high” polygenic risk scores for neurodevelopmental traits such as autism, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia—though the scientists themselves emphasize that DNA on its own cannot determine behaviour.

Kallmann syndrome is a rare genetic disorder that disrupts the normal development of the hypothalamus, resulting in reduced or absent sex hormone production, a failure of the testes to descend, diminished pubic hair growth and often an impaired sense of smell (anosmia). One of its biological manifestations in males can include a micropenis (commonly defined as a penis length significantly below the average) and undescended testicles—conditions that may correspond to wartime rumors about Hitler’s anatomy. The researchers estimate Hitler faced roughly a 1-in-10 chance of having a micropenis.

The implications of these findings are multifaceted. For decades, historians have documented Hitler’s curious detachment from intimate relationships, his obsession with politics and ideology, and the absence of any children despite a long tenure in power. Some have speculated whether a profound personal insecurity or sense of otherness drove him to cling to identity, power and symbolic domination instead of family life. In this context, the revelation that he may have had a serious sexual development disorder offers a new lens through which to interpret his psychology. Historian Alex Kay of the University of Potsdam is quoted in the documentary as saying that this condition “could be the answer we’ve been looking for” in explaining Hitler’s social detachment and political focus.

It is worth stressing, however, that the researchers themselves caution against drawing simplistic lines of causation: having Kallmann syndrome or elevated genetic risk for neurodevelopmental traits does not mean one is predisposed to brutality, genocide or mass murder. Indeed, experts like Simon Baron-Cohen emphasize that behaviour is never 100 % genetic. The team stresses that these biological clues shed light on the man’s vulnerabilities, not his monstrous choices—and they do not diminish the moral responsibility of Hitler for the horrific actions carried out under his command.

Another key finding from the DNA study is the debunking of the persistent rumor that Hitler had Jewish ancestry. The genetic profile shows no evidence of Jewish lineage on the male side, reinforcing his Austrian-German identity and undermining claims that his toxicity derived from a hidden background.

The study opens sensitive ethical questions: Should we analyse the genomes of tyrants and dictators to gain psychological or historical insight? The researchers argue yes—because ignoring such possibilities places historical figures on a pedestal beyond scrutiny. “If we don’t do it, someone else will,” King says. Yet critics caution that the public may misinterpret the findings, portraying Hitler’s evil as “just his genes,” thereby minimizing the ideological, political and systemic factors in Nazi atrocities.

From a historical-psychological standpoint, the study invites re-evaluation of certain aspects of Hitler’s personality: his profound sense of inadequacy, his suppression of intimacy, his relentless projection of power. For instance, the medical record from 1923 (while he was imprisoned after the failed Munich Beer Hall Putsch) recorded “right-side cryptorchidism,” meaning an undescended right testicle. The new DNA evidence of Kallmann syndrome may help explain why he may have experienced physical and neurodevelopmental issues, which could have interacted with his psychological makeup. That is not to explain away his atrocities, but rather to offer a fuller portrait of the man behind the mask.

Importantly, the findings do not suggest that Hitler’s sexual anatomy was the cause of his ideology, or that the disorder justified his actions. The documentary and associated research are clear: the biological data provides “another layer of information” in understanding a complex historical figure—but it does not override responsibility, ideology or environment. As one researcher put it: “You cannot see evil in a genome.”

The release of the documentary marks a new phase in how historians, psychologists and geneticists might intersect in exploring major historical figures. But it also revives long-standing concerns about sensationalism. Some commentators worry that the evocative headline—“micropenis and still one ball”—reduces historical inquiry to tabloid fodder and distracts from the political, ideological and human horrors of the Nazi regime. The Guardian for example describes the programme as “an odd argument”—noting historical sources attribute Hitler’s body-burning order to his fear of humiliation, not necessarily any genital anxiety.

For readers, the take-away is this: the new research underscores that the architecture of evil is rarely simple. Biology may play a role in forming the contours of a person’s life—vulnerability, physical difference, trauma—but it does not dictate choice. The study invites us to view Hitler not merely as the monstrous embodiment of hatred but as a deeply troubled human being whose inner life included physical and psychological dimensions. That insight does not absolve, excuse or soften his crimes—it merely deepens the historical record.

As the documentary airs and the peer-reviewed paper is published, historians will debate how much weight to give these findings. For now, the story stands as a vivid example of how modern science can intersect with historical investigation, giving fresh data and fresh caution in equal measure. In confronting the horrors of the past, we are reminded that even the darkest figures remain human: flawed, secretive, manipulated by both inner and outer forces—and fully accountable for the choices they made.