In a Shocking Betrayal, Louisiana Middle School Expels 13-Year-Old Victim After She Swats at Boy Sharing Her AI-Generated Nude – Family Vows Federal Lawsuit as Outrage Grows

The fluorescent lights of the Lafourche Parish School Board meeting room hummed softly on November 5, casting long shadows across the wooden dais where a row of officials sat in quiet resolve. In the audience, a 13-year-old girl clutched her mother’s hand, her wide eyes fixed on the floor as if willing it to swallow the weight of the room. Flanked by her parents, she was a small figure amid the murmur of supporters and the click of reporters’ pens, her straight brown hair falling like a curtain over a face that had aged beyond its years in just a few short months. This wasn’t just any school board gathering; it was a reckoning, a desperate plea for justice in a story that had unraveled her world with the cruel precision of a digital blade.

Her name hasn’t been released—protecting her privacy is one small mercy in this saga—but to those who know her, she’s simply the bright eighth-grader from Sixth Ward Middle School whose laughter once echoed through the hallways of this quiet corner of Louisiana. That laughter faded in late August, just as the new school year bloomed with the sticky heat of summer’s end. What began as whispers among classmates turned into a nightmare no child should endure: AI-generated images, fabricated nudes superimposing her innocent face onto exposed bodies, circulating like wildfire on Snapchat. The platform’s ephemeral nature made them ghosts—gone in seconds, but the scars they left? Those lingered, festering into taunts and trades that followed her from classroom to cafeteria to the yellow school bus rumbling home.

She did everything right, or so the adults had always taught her. First, she confided in a teacher, her voice trembling as she described the photos that made her stomach churn. Then, the guidance counselor, who nodded sympathetically but offered little beyond a vague promise to look into it. She even approached a school resource officer, the one uniformed figure meant to be a beacon of safety, only to hear the same refrain: It would be handled. Desperate, she mentioned wanting to call her father, but officials brushed it aside. “We don’t need to get parents involved right now,” they said, as if shielding her from the very support that might have steadied her shaking world. All the while, the images kept spreading, the boys involved—emboldened by impunity—flashing their phones like trophies, their jeers a soundtrack to her unraveling day.

By the time she boarded the bus that afternoon, the pressure had built to a breaking point. The air inside was thick with the scent of vinyl seats and adolescent sweat, the engine’s rumble a futile cover for the snickers rippling through the back. One boy, the ringleader in her torment, held up his phone again, the fabricated image glowing mockingly in the dim light. In a flash of raw, unfiltered desperation, she swatted at it—not a calculated strike, her lawyers would later clarify, but a reflexive knock to make it disappear, to reclaim a sliver of the dignity they’d stolen. The bus lurched to a stop, and what followed was swift and unyielding: suspension, then expulsion. For violence, the school said. Zero tolerance. The girl who had begged for protection was now the one cast out, her desk empty, her future uncertain.

Word of the expulsion trickled out slowly at first, a hushed scandal in the close-knit community of Thibodaux, where Sixth Ward Middle sits amid sugarcane fields and bayou whispers. But when her family learned the full scope—the school’s inaction, the unchecked harassment—it ignited a fire they couldn’t contain. Her father, a man whose calloused hands spoke of honest labor and unwavering love for his only daughter, watched as her grades plummeted and a shadow of depression settled over her once-vibrant spirit. “She gave up,” he would later say, his voice cracking during his testimony at that fateful board meeting. “The expulsion was way too extreme for a little girl who has never been in trouble in her life. A suspension would’ve been perfectly fine with me—I always believe in accountability. But this? This broke her.”

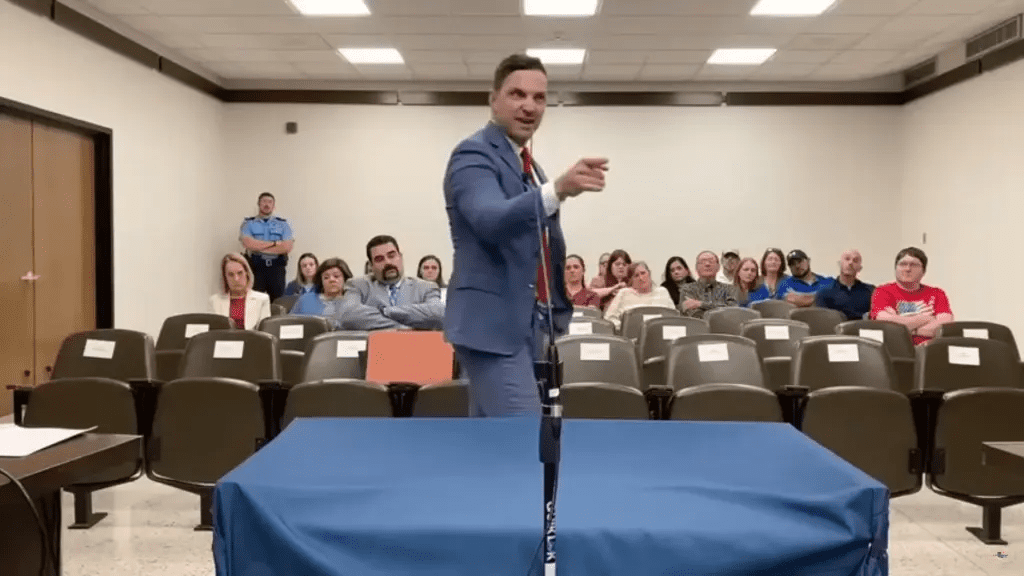

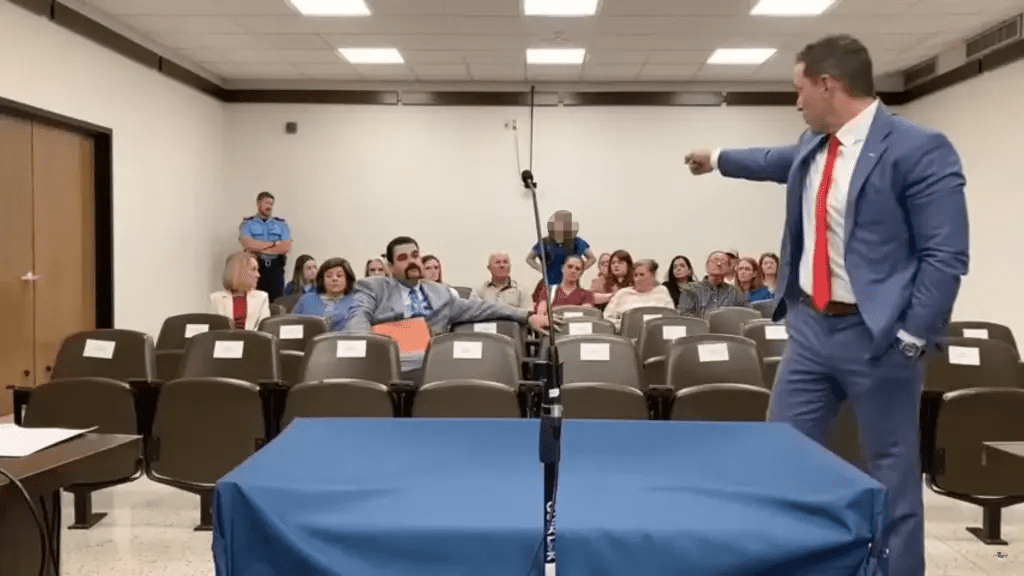

The family’s attorneys, a fierce team from Baton Rouge led by Benjamin Comeaux and Matt Ory, stepped in like guardians at the gate. They pored over the details, piecing together a timeline of betrayal: reports ignored, phones not confiscated, no separation of the victim from her harassers. “She did an excellent job of notifying those who needed to be notified,” Comeaux declared at the meeting, his words slicing through the room’s tension like a knife. “And adults failed her.” Ory, pacing with the measured fury of a prosecutor denied justice, didn’t hold back. “This is how kids become suicidal,” he thundered, his finger jabbing toward the board. “This, right here, and you guys are saying it’s okay! She asked for help—not once, not twice. She is the victim. And now you took her out of school and expelled her?”

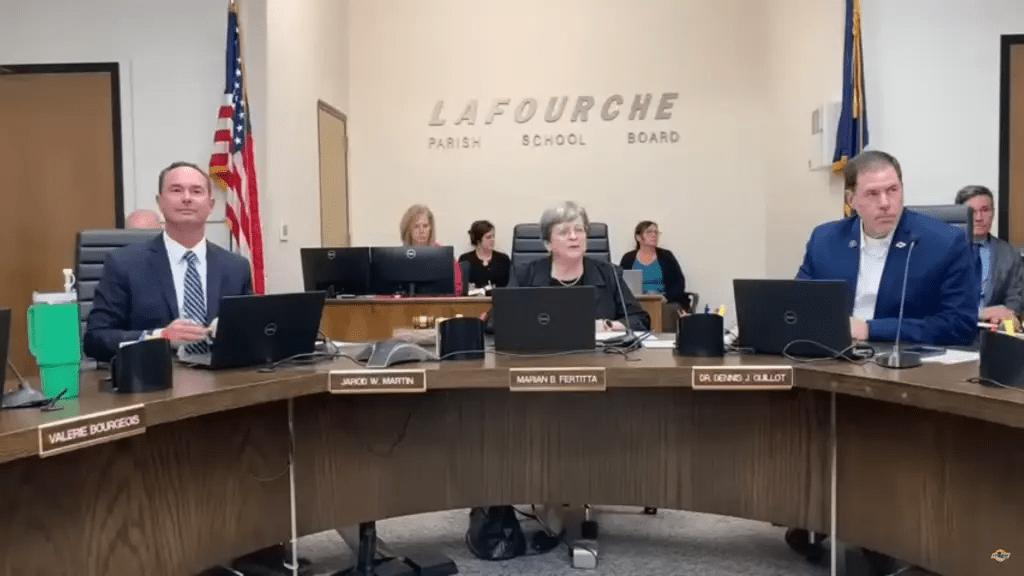

The board room erupted in murmurs as a video clip played on the overhead screen—a grainy, heart-wrenching glimpse of the bus altercation, the girl’s arm flailing in what looked less like aggression and more like a drowning soul grasping for air. Superintendent Jarrod Martin, a tall figure in a crisp shirt and tie, leaned into the microphone, his expression a mask of conflicted authority. “Sometimes in life, we can be both victims and perpetrators,” he said, the words hanging heavy. “Horrible things happen to us, and we get angry and do things. The video you all watched depicts something that’s very difficult to defend.” Board member Valerie Bourgeois nodded along, adding her own measured take: The girl was undoubtedly a victim, she conceded, but expulsion wouldn’t have happened “if she had not hit the young man.” Why not settle it outside school? she wondered aloud, as if playground politics could eclipse the digital violation that preceded it.

In the end, the board didn’t fully relent. They upheld the expulsion but amended it, allowing the girl to return to Sixth Ward on probation—a compromise that felt to her family like a half-hearted bandage on a gaping wound. She stepped back into those hallways this week, backpack slung over her shoulder, but the victory rang hollow. Probation meant watchful eyes, restricted privileges, a record that could shadow her for years. And the boys? One, the alleged creator and sharer of the images, had been arrested back on September 15 by the Lafourche Parish Sheriff’s Office. Charged with 10 counts of unlawful dissemination of images created by artificial intelligence under Louisiana’s relatively new deepfake statute—a law enacted in 2023 to combat just this kind of synthetic cruelty—the boy faced serious consequences, announced publicly only on November 10. Sheriff Craig Webre, a no-nonsense lawman with decades on the force, made it clear: More arrests could follow as the investigation deepens. The girl, mercifully, would face no charges. “Due to the totality of the circumstances,” Webre put it, a nod to the context that turned her swat from crime to cry for help.

But for the family, the school’s response wasn’t just inadequate; it was a profound failure of duty. Attorneys Greg Miller and Morgyn Young, bolstering the legal front, laid out the charges they plan to bring in federal court in New Orleans: a sexually hostile environment in violation of Title IX, the federal law mandating equal protection from gender-based discrimination in education; negligence as mandatory reporters who should have escalated the abuse immediately; and a blatant disregard for the girl’s pleas. “They almost completely ignored their legal obligations,” Miller said, his tone laced with disbelief. “Nobody took any action to confiscate cell phones, to put an end to this. It’s pure negligence on the part of the school board.” Young, focusing on the emotional toll, drove the point home: “Regardless of whether the image was real or not, it gave a realistic effect, and therefore it is still sexual exploitation of this child.” The message to young girls everywhere, they argued, was reprehensible: Speak up, and still, you might be the one punished.

Martin’s defense, issued through a statement to local outlets, painted a different picture—one of protocol followed to the letter. “Any and all allegations of criminal misconduct on our campuses are immediately reported to the Lafourche Parish Sheriff’s Office,” he wrote. “After reviewing this case, the evidence suggests that the school did, in fact, follow all of our protocols and procedures for reporting such instances.” It’s a stance that underscores the district’s commitment to a safe learning environment, one where violence, no matter the provocation, draws consequences. Yet in the quiet aftermath, as the girl navigates her probationary return, the cracks in that commitment glare back: Why couldn’t investigators locate the Snapchat specters? Why board a bus with known harassers? And in a era where AI tools are as accessible as a smartphone app, how does a school prepare for threats that vanish like smoke?

This isn’t an isolated heartbreak; it’s a harbinger of a storm brewing in classrooms across America. By 2025, reports of AI-generated deepfakes targeting students have surged, with surveys showing that 15 percent of teens encountering such abuse firsthand. Organizations like Thorn, dedicated to ending child sexual exploitation, note a doubling in AI-fueled incidents over the past year alone, fueled by apps that democratize deception. In schools from California to New York, similar tales emerge: Girls shamed into silence, boys facing misdemeanor charges under patchwork laws, administrators scrambling to update policies that predate the technology. Louisiana’s deepfake statute, a pioneer in criminalizing the nonconsensual creation and sharing of such images, offers a framework—fines up to $100,000 and jail time for repeat offenders—but enforcement lags, especially when perpetrators are minors.

Federally, momentum builds. The DEFIANCE Act, signed into law earlier this year, empowers victims to sue creators of nonconsensual deepfake porn, a civil lifeline that could bolster cases like this one. States like Texas and Virginia have followed suit with bans on deepfake dissemination in educational settings, mandating swift takedowns and counseling for survivors. Yet experts warn it’s not enough. “We’re playing catch-up to a tool that’s evolving faster than our safeguards,” says Dr. Elena Vasquez, a cyberpsychologist at Tulane University who studies digital trauma in youth. Her research highlights the psychological ripple: Anxiety spikes, trust erodes, and for girls like this 13-year-old, the betrayal cuts deepest when it comes from those sworn to protect.

As the federal lawsuit looms, the family clings to a fragile hope. The girl’s father, speaking after the meeting with a resolve tempered by exhaustion, emphasized shared accountability—a philosophy that echoes through their fight. “She was wrong,” he admitted of the swat, “but the school was also wrong by putting her in that place with the little boy at the time. In my mind, it goes both ways.” For now, she’s back in class, piecing together lessons amid wary glances, her spirit a testament to resilience forged in fire. But the road ahead is long: Therapy sessions to mend the fractures, advocacy to amplify her voice, and a courtroom battle that could redefine how schools shield their most vulnerable.

In Thibodaux’s humid embrace, where live oaks drape like weary sentinels over cracked sidewalks, this story resonates beyond one girl’s pain. It’s a clarion call for a reckoning with technology’s dark underbelly, a plea that no child should ever have to choose between silence and exile. As winter approaches the bayous, the Lafourche Parish community watches, waits, and wonders: Will justice finally catch up to the ghosts in the machine? For this young survivor and countless others, the answer can’t come soon enough.