Christopher Bernardini’s Claims of Overbilling and Ghost Services at Gateway Community Services Spark Probe into State’s $28M Payments

The faint hum of fluorescent lights in a Portland, Maine, community center on the morning of December 8, 2025, did little to ease the tension in Christopher Bernardini’s voice as he sat with a small group of reporters, his hands clasped around a thick folder of redacted invoices and emails that painted a picture of quiet deception. At 45, Bernardini—a former “billing guru” at Gateway Community Services for seven years until his April 2025 departure—had come forward with allegations that the Somali-American-led nonprofit had defrauded Maine’s Medicaid program, known as MaineCare, out of millions through falsified claims for services to low-income and disabled clients, many never delivered. “I was told to bill hours that didn’t happen—clients calling to say no one showed up, but the invoices went in anyway,” Bernardini told NewsNation in an exclusive interview that day, his tone a mix of resignation and resolve, the folder’s contents a testament to the ethical bind that led him to whistleblow. For Bernardini and the Maine taxpayers who fund MaineCare’s $2.5 billion annual budget serving 400,000 residents, the claims evoke a profound unease—a betrayal of trust in a system meant to lift the vulnerable, where one organization’s alleged grift could have diverted resources from families relying on therapies and home care. As the state launches a probe and national eyes turn to similar scandals in Minnesota, Bernardini’s story stirs a gentle call for accountability, a reminder that in the quiet ledgers of public programs, every dollar misspent leaves a ripple of hardship for those it was meant to help.

Gateway Community Services, a Portland-based nonprofit founded in 1992 to provide behavioral health and support for the disabled, has long been a pillar in Maine’s social services landscape, its offices spanning from Lewiston to Bangor and serving 5,000 clients yearly with programs for autism therapy, housing stabilization, and personal care. Under CEO Abdullahi Ali, a Somali-American refugee who arrived in the U.S. in 1990 and earned a PhD in public policy from the University of Southern Maine, the organization grew to $28.8 million in MaineCare revenue from 2015 to 2023, per Freedom of Access Act documents obtained by The Maine Wire. Ali, 50, who ran for president of Somalia’s Jubaland region in 2024 while leading Gateway, has defended the company as a “passion for helping people,” tweeting on December 3 in response to reports: “I make no apologies for building a successful business in Maine… and running for office in Jubaland.” But Bernardini, who handled billing for the autism and personal support specialist programs from 2018 to 2025, alleges a pattern of fraud: Duplicate invoices for unperformed sessions, staff paid for ghost hours, and $800,000 overbilled in a 2015-2017 DHHS audit that Gateway settled without admitting wrongdoing. “Clients would call furious—no one came for their kid’s therapy, but I’d get orders to bill it anyway. It got worse—PPP loans handed out like candy to non-workers,” Bernardini said, his folder a catalog of emails directing $2,000 bonuses to unqualified staff during 2020’s pandemic relief.

Bernardini’s allegations, detailed in a December 1 op-ed for The Maine Wire and expanded in his NewsNation interview, echo the Feeding Our Future scandal in Minnesota, where Somali-American operators stole $250 million in child nutrition funds from 2022 to 2024, with $50 million recovered but $200 million untraced, some allegedly to Al-Shabaab. In Maine, Gateway’s $28.8 million MaineCare haul from 2015 to 2023 included $12 million for autism services under Section 28, where Bernardini claims 30% of hours were fabricated. “I’d get calls from parents—’Where’s the therapist?’—and superiors would say bill it, ‘they’ll come next time,'” he recounted, his voice steady but eyes distant as he described the ethical erosion that led to his exit. The Maine DHHS, which audited Gateway in 2017 and recovered $800,000, confirmed no ongoing probes but launched a review on December 3 following Bernardini’s claims, spokesperson Jackie Farwell stating, “We take all allegations seriously and are examining records.” Gateway, which received a $1.2 million PPP loan in 2020 for 50 employees, did not respond to requests for comment, but Ali’s LinkedIn profile lists his Jubaland candidacy, where he boasted of funding militias in Kenyan TV interviews—a detail that has fueled speculation of diverted funds, though no evidence ties it to MaineCare.

The human cost of such schemes, if proven, weighs heaviest on the families Gateway serves—low-income and disabled Mainers who depend on the nonprofit’s therapies for daily stability. In Lewiston, 42-year-old single mother Tanya Wilkins relies on Gateway for her 8-year-old son Noah’s autism support, his weekly sessions a $200 hourly lifeline covered by MaineCare. “Noah’s words came from those visits—without them, he’s lost in silence,” Wilkins said over a December 4 call from her trailer, her voice thick with the fear of disruption if fraud halts services. Wilkins’s story, one of 5,000 clients Gateway served in 2024 per its annual report, highlights the stakes: MaineCare’s $2.5 billion budget covers 400,000, 60% children and disabled, with autism programs like Section 28 serving 2,000 kids at $100 million yearly. Bernardini’s claims—30% ghost billing—could mean $3.6 million diverted from 2015 to 2023, funds that could have expanded Wilkins’s sessions or hired more therapists. “If it’s true, it’s not just money—it’s my boy’s voice stolen,” Wilkins said, her hands folding Noah’s drawing of a family picnic, the crayon lines a fragile dream amid the probe’s uncertainty.

Ali’s dual role—Gateway CEO and Jubaland candidate—adds layers to the allegations, his 2024 campaign platform promising “security and development” funded by diaspora remittances, a detail The Maine Wire linked to hawala transfers in Bernardini’s op-ed. Ali, who arrived as a refugee in 1990 and built Gateway from a $500,000 startup to $30 million operation, has defended it as “community service,” his PhD thesis on refugee integration a cornerstone. “I have a passion for helping people,” Ali tweeted December 3, but Bernardini’s emails show directives to bill unperformed hours, a practice he claims escalated during COVID with $1.2 million PPP loans paid to non-workers. The Maine DHHS audit in 2017 flagged $800,000 overbilling, settled without admission, but Bernardini alleges it continued, with 2020 bonuses of $2,000 to unqualified staff. “It was wrong—I reported it internally, but nothing changed,” he said, his whistleblower status protected under Maine’s 2019 law, though he fears retaliation in Portland’s tight-knit Somali community of 2,730 per 2023 census data.

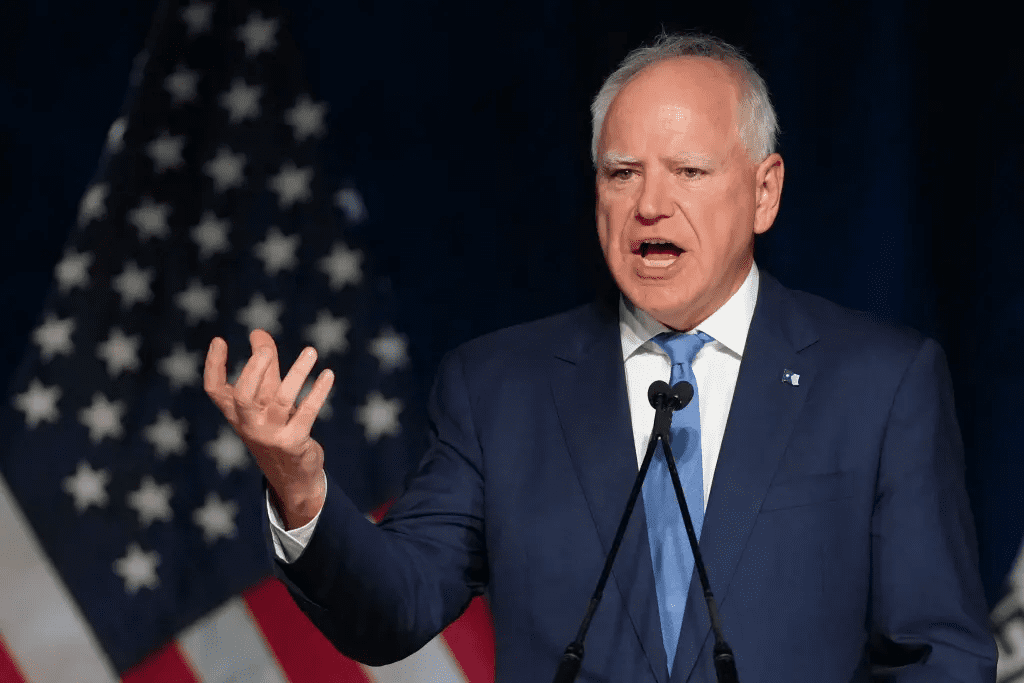

Public response, from Augusta offices to Lewiston living rooms, forms a mosaic of outrage and introspection, a state pausing holidays to ponder trust’s fragility. In a Portland town hall on December 5, 150 gathered, Wilkins speaking: “Gateway helped Noah speak—now, fraud questions it all?” The room, filled with parents and providers, nodded as Rep. Laurel Libby (R) called for a special prosecutor: “Billions at risk—transparency now.” Libby’s words, from a district with 20% Somali residents, balanced concern with care, avoiding blame on the community. Social media, under #MaineCareFraud, trended with 1.2 million posts—from Bernardini sharing redacted invoices to advocates posting client stories. A viral TikTok from 25-year-old organizer Sofia Ramirez garnered 2 million views: “Fraud hurts us all—but let’s fix without fear.” Ramirez’s clip, from a Lewiston clinic, highlighted stakes—5,000 clients, $28.8 million revenue, a probe that could halt services for 1,000 disabled.

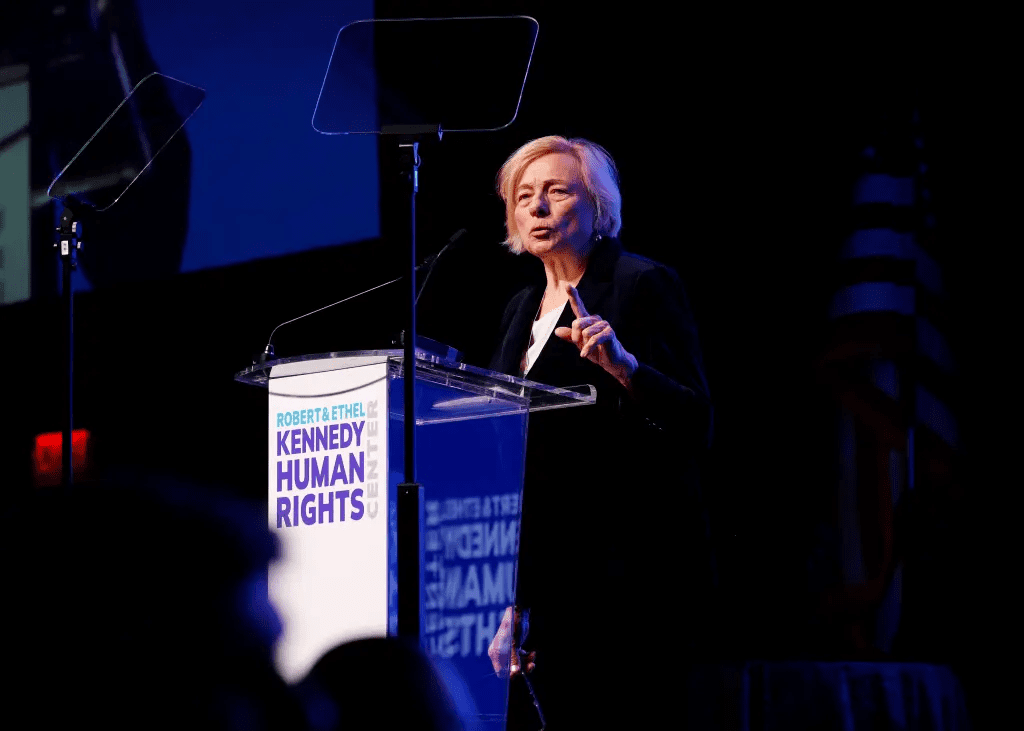

Gov. Janet Mills’s administration, which expanded MaineCare to 400,000 since 2019, vowed cooperation: “We’re investigating—$20 million recovered statewide since 2022.” But the whistleblower’s ties to GOP gubernatorial candidate Ben Midgely, who raised the scandal in a December 1 Maine Wire op-ed, add political heat, Midgely calling it “outrageous betrayal of taxpayers.” For Wilkins, the politics fade: “Noah needs therapy—fraud or not, help him speak.” As December’s holidays unfold, Bernardini’s claims invite reflection—a system’s trust tested, Wilkins’s drawing a small act of hope. In Portland centers and Lewiston homes, thanks endures—in hands helping the vulnerable, family the true service.