From Prison to Policy: Mysonne Linen’s Redemption Story Takes Center Stage in NYC Transition

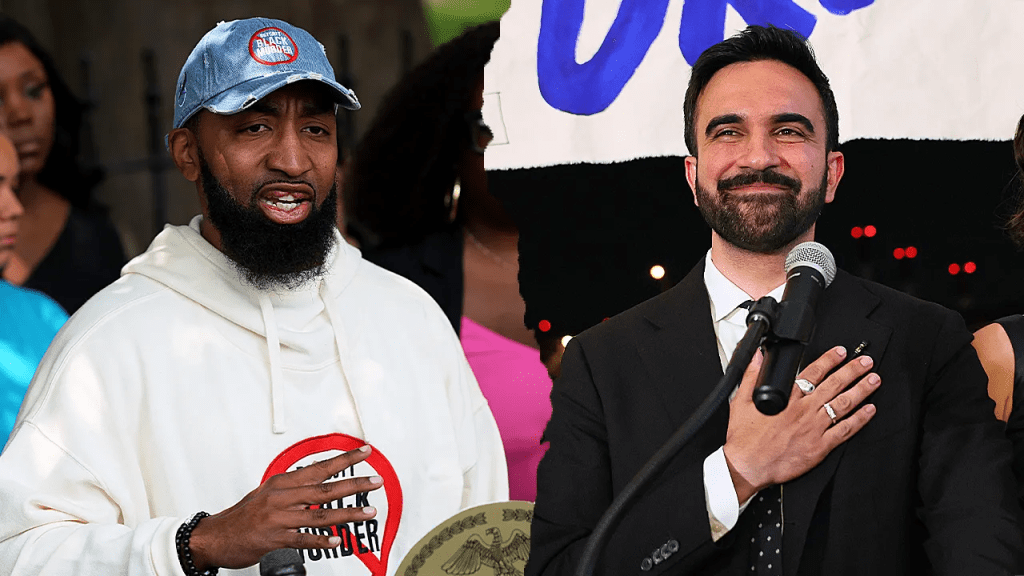

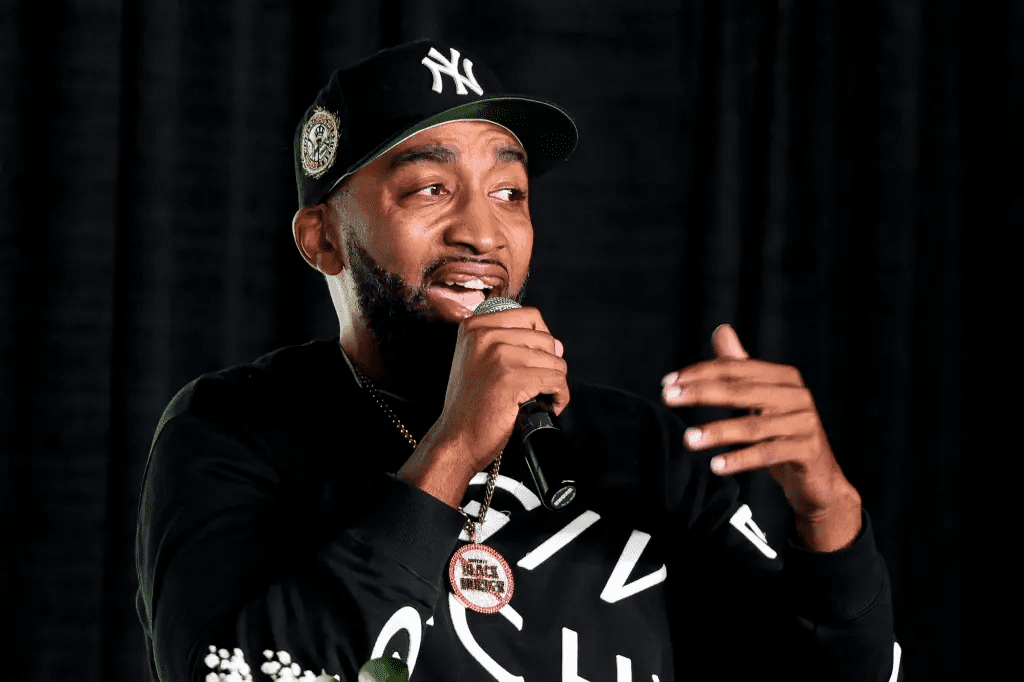

In the vibrant heart of Harlem’s Apollo Theater district, where the marquee’s glow has long illuminated stages for legends from Ella Fitzgerald to Lauryn Hill and the air hums with the legacy of voices that rose from struggle to stardom, Mysonne Linen stood before a crowd of 200 at a December 5, 2025, community forum, his microphone in hand and his words weaving a tapestry of hard-won wisdom from a life that had once led him to prison bars. Linen, 47, a hip-hop artist and activist whose lyrics on “The Life of a Felon” in 2001 chronicled the cycles of incarceration and redemption, was there to discuss his new role on New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani’s public safety and criminal justice transition team—a appointment that had sent ripples through the city just days after Mamdani’s November 4 landslide victory. For Linen, whose seven-year sentence for armed cab robberies in 1999 at age 21 had been a dark chapter in a Brooklyn youth marked by poverty and poor choices, the invitation was more than a title; it was a full-circle moment, a chance to channel the pain of his past into policies that could spare others the same path. “I’ve been where the system breaks you—now, I’m here to help fix it,” Linen said to the room, his voice resonant with the rhythm of someone who’s turned bars of iron into bars of verse, his presence a quiet challenge to the stereotypes that once defined him. Mamdani, the 33-year-old democratic socialist whose upset win as the city’s first Muslim and South Asian mayor promised a “New York for all,” chose Linen for his lived experience, a decision that has sparked both applause for inclusivity and whispers of concern in a metropolis still healing from 2020’s unrest. In a transition where the stakes for safety feel as personal as a neighborhood walk home, Linen’s story isn’t just a resume addition; it’s a human bridge from the shadows of conviction to the light of contribution, a reminder that in the grand narrative of reform, the most compelling voices often rise from the places we’ve fallen hardest.

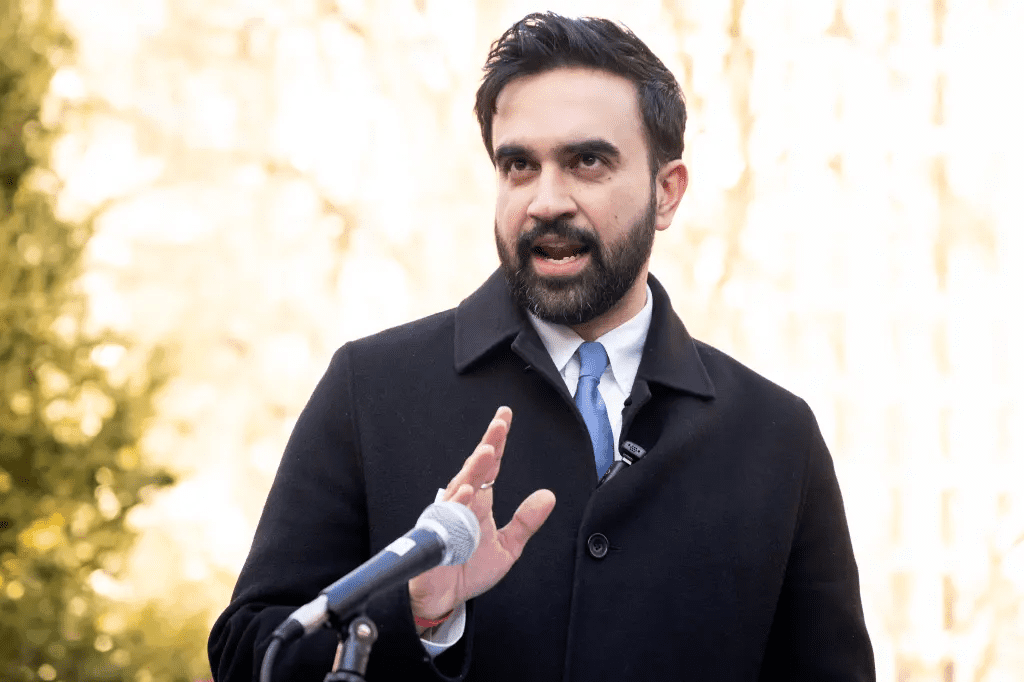

Linen’s appointment, announced December 3 as part of Mamdani’s 25-member transition team led by chief of staff Dean Fuleihan, a de Blasio-era budget wizard with a knack for balancing $85 billion ledgers, placed the rapper alongside experts like criminologist Barry Friedman and former NYPD Commissioner William Bratton in a group tasked with overhauling the city’s $11 billion public safety apparatus. Mamdani, elected with 68% in the general after a 52% primary win that flipped the mayor’s office progressive for the first time since Fiorello La Guardia’s 1930s reforms, campaigned on bold strokes: Ending stop-and-frisk, investing $1 billion in mental health response teams, and auditing the NYPD’s $5.8 billion budget to redirect funds to community violence interrupters. “Safety isn’t just cops—it’s counselors, coaches, neighbors,” Mamdani said at the announcement in a Harlem church, his voice rising amid cheers from 300 supporters, the crowd a diverse blend of Black Lives Matter activists and union leaders who’d knocked on 200,000 doors in the rain. Linen’s inclusion, highlighted in Mamdani’s statement as “bringing the perspective of those who’ve known the system’s failures firsthand,” drew immediate attention: The 1999 convictions—armed robbery of three cab drivers in Brooklyn, for which he served seven years at Sing Sing and Otisville—had been a turning point, Linen emerging in 2006 with a mixtape that channeled his time inside into calls for reform. “Mysonne’s voice is essential— he’s lived the consequences and learned the lessons,” Mamdani added, his words a nod to the team’s 40% formerly incarcerated members, a deliberate choice to center those touched by justice’s rough edges.

Linen’s path from prisoner to policy advisor is a narrative of transformation that has inspired thousands in New York’s hip-hop and reform circles, a journey that began in the Brownsville projects where he grew up in the 1980s, the son of a single mother juggling two jobs amid crack epidemic violence. At 20, a string of armed robberies—stealing $200 from cabbies to fund a music dream—landed him in prison, where he spent seven years reading Malcolm X and writing bars that would become “The Life of a Felon.” Released in 2006 on parole, Linen founded the H.O.O.D. (Helping Our Own Down) Movement, mentoring at-risk youth in Brooklyn with workshops on conflict resolution and entrepreneurship, reaching 5,000 teens since 2010 per program reports. “Prison broke me open—now I use those cracks to let light in,” Linen said at the forum, his lyrics from “Felon for Life” underscoring his talk on recidivism’s 67% rate in New York, per 2024 DOCCS data. His work, blending rap battles with restorative justice circles, has earned nods from figures like Jay-Z, who collaborated on a 2022 prison reform track, and the Vera Institute, which partnered for a 2025 Brooklyn pilot reducing reoffense 20%. For Linen, father to a 15-year-old son from a previous relationship, the appointment is personal: “My boy’s watching— I want him to see second chances lead to change.”

Mamdani’s choice, part of a transition emphasizing “lived experience” over elite credentials, has drawn praise from reform advocates but raised eyebrows in traditional safety circles. Fuleihan, 74, a Lebanese-American whose de Blasio days balanced budgets through fiscal cliffs, sees Linen as an asset: “Mysonne’s insight on reentry will shape smarter policies.” The team, announced December 3 at a Brooklyn warehouse with 400 attendees, includes 10 formerly incarcerated individuals, a 40% quota Mamdani calls “intentional equity.” Bratton, 77, the former NYPD commissioner whose “broken windows” approach cut crime 50% in the 1990s, tempered his support: “Lived experience is valuable, but expertise saves lives.” Bratton’s words, shared in a December 4 Post interview, reflect a city where homicides fell 12% in 2025 to 386, per NYPD CompStat, but shootings rose 5% amid migrant strains. Mamdani’s platform—ending qualified immunity, $1 billion for violence interrupters—resonates with 62% of voters per a December 2025 Siena poll, but 45% worry about “soft on crime” perceptions.

Linen’s past, detailed in his 2006 plea to seven years for three armed robberies—stealing $200 from cabbies at gunpoint—has been a chapter of growth, his parole in 2006 followed by a vow to “never go back.” Released at 28, he channeled energy into H.O.O.D., partnering with the Fortune Society for job training that placed 300 ex-offenders in 2024. “I robbed to eat—now I teach to thrive,” Linen said at the forum, his son in the front row nodding. Critics like the NYPD’s Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association called the appointment “tone-deaf,” PBA president Patrick Lynch saying December 5, “Safety needs pros, not ex-cons.” Lynch’s words, viewed 800,000 times on X, drew counter from the Vera Institute: “Reform works when we listen to those who’ve lived it.”

For Linen’s son, 15 and a high school sophomore, the role is inspiration: “Dad’s story shows mistakes don’t end you.” The family, in a Brooklyn brownstone, blends hip-hop nights with homework help, Linen’s mixtapes a soundtrack to growth. Mamdani’s vision, with Linen advising on reentry programs that could house 5,000 formerly incarcerated, promises change: “We’ll build circles, not cells.”

The appointment, a bridge from past to policy, invites reflection on redemption’s reach. For Lynch in statements, Lynch’s critics in reports, and Linen’s son in school, it’s a moment of possibility—a gentle affirmation that in New York’s vast chorus, reformed voices harmonize justice, one lived lesson at a time.