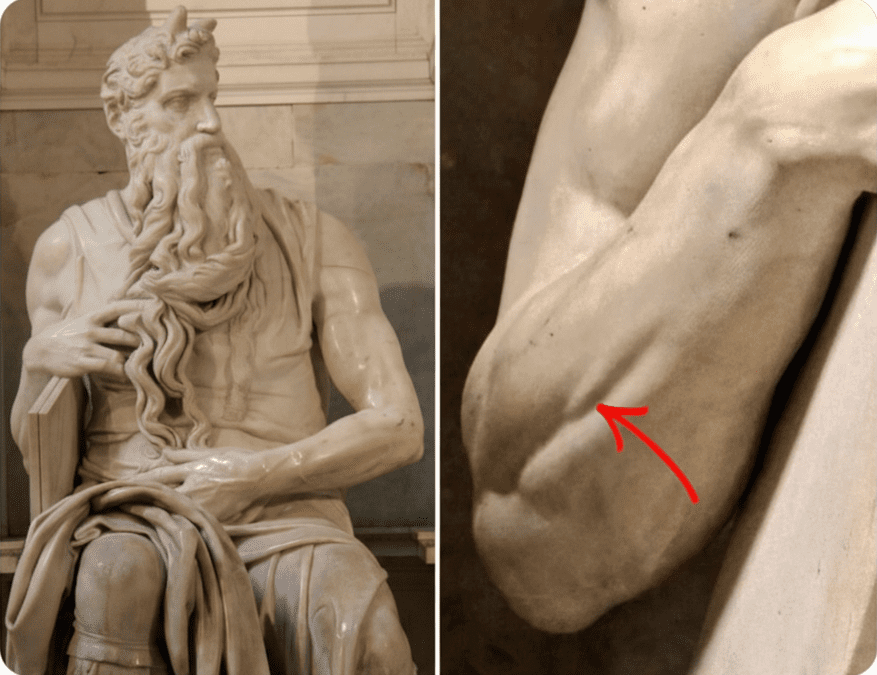

Michelangelo’s “Moses” Features a Hidden Muscle That Only Appears When Lifting the Pinky, Revealing His Genius Understanding of Human Anatomy

There are moments in art history that remind us how close genius can come to divine precision — and Michelangelo’s sculpture of Moses is one of them. At first glance, it’s a towering masterpiece of Renaissance craftsmanship, carved from marble with commanding presence. But hidden in its lifelike detail lies a secret so subtle that it escaped notice for centuries: a muscle that only appears when a person lifts their pinky finger. This small but extraordinary detail has become one of the most striking proofs of Michelangelo’s deep and almost surgical understanding of the human body.

The muscle in question is known as the extensor digiti minimi, a narrow muscle on the outer forearm responsible for extending the little finger. It’s a detail so minute, so physiologically specific, that most people would never notice it in daily life. Yet Michelangelo not only knew of its existence but chose to carve it into Moses — and positioned the statue’s hand in such a way that the muscle would naturally flex, just as it does in a living person when lifting the pinky. For a sculptor working in the early 1500s, long before modern anatomical diagrams or dissection laws made such knowledge accessible, this level of precision is astonishing.

The story behind that precision goes back to Michelangelo’s lifelong obsession with anatomy. He studied the human form relentlessly, often dissecting cadavers in secret despite religious prohibitions. For him, understanding how muscle, skin, and bone interacted wasn’t just a technical necessity — it was the foundation of truth in art. He once said that sculpture was about freeing the figure trapped inside the stone, and to do that, he had to know the structure of the human body intimately. His work reflects not just observation but comprehension — the kind of knowledge that bridges science and art seamlessly.

Moses, created between 1513 and 1515 for the tomb of Pope Julius II, captures the prophet in a moment of divine tension, holding the tablets of the Ten Commandments. Every line of his body feels alive — from the furrowed brow and flowing beard to the veins pressing against marble skin. The presence of the extensor digiti minimi muscle, visible only because Moses’s pinky is slightly raised, shows how Michelangelo didn’t just sculpt what he saw, but what he understood. He built anatomy into emotion, giving the statue a sense of movement frozen in time.

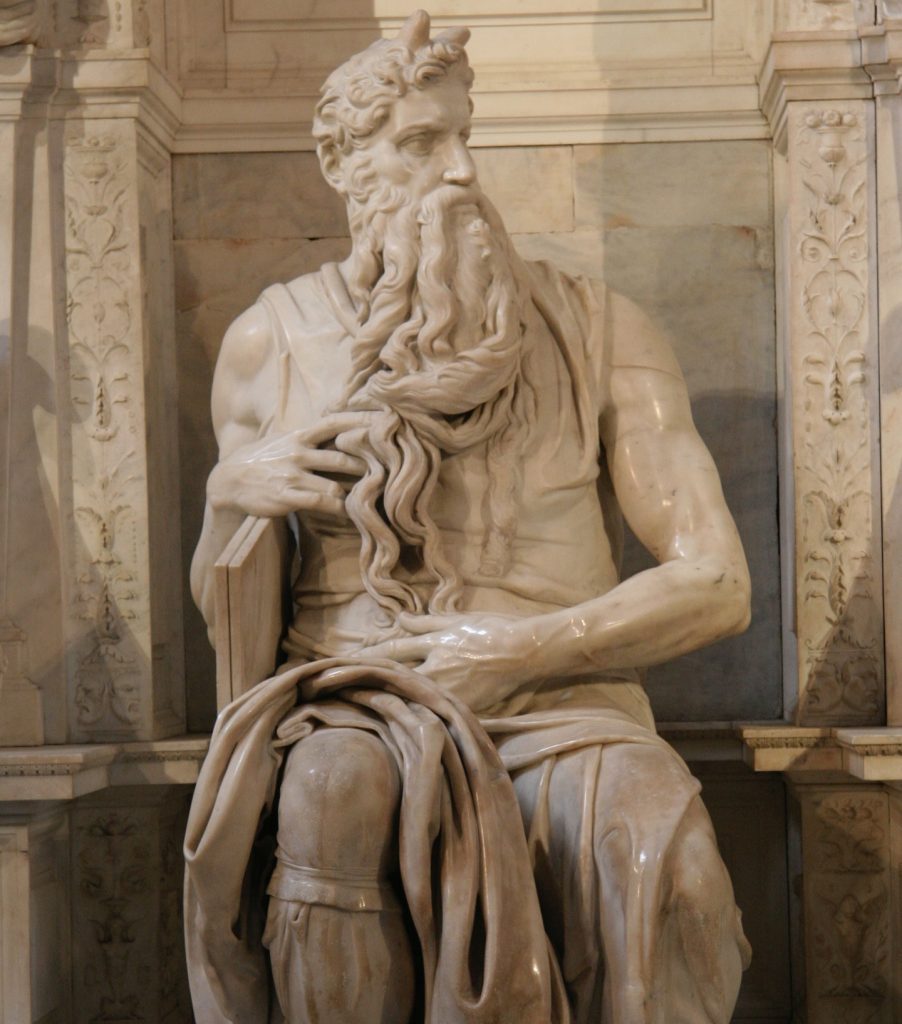

When viewers stand before Moses in Rome’s San Pietro in Vincoli, they often speak of its spiritual weight. The sculpture feels ready to move, as if it could rise and speak at any moment. That sense of life comes not from imagination alone but from accuracy — the invisible, painstaking anatomical truths embedded beneath the surface. It’s as if Michelangelo carved not just the body, but the soul’s framework itself.

This hidden muscle detail, now famous among art historians and anatomy experts, has come to symbolize the Renaissance spirit — the merging of art, science, and faith into a single act of creation. Michelangelo didn’t separate beauty from biology; he understood that one flowed from the other. His mastery wasn’t simply in depicting muscles, but in knowing when and why they moved — and capturing that moment of potential energy forever in stone.

In an age when most sculptures idealized the human form, Michelangelo’s Moses represented something revolutionary: truth. His anatomical awareness elevated his work from artistry to revelation. The hidden muscle might be a small detail, but it stands as quiet proof that genius often lies in what others overlook.