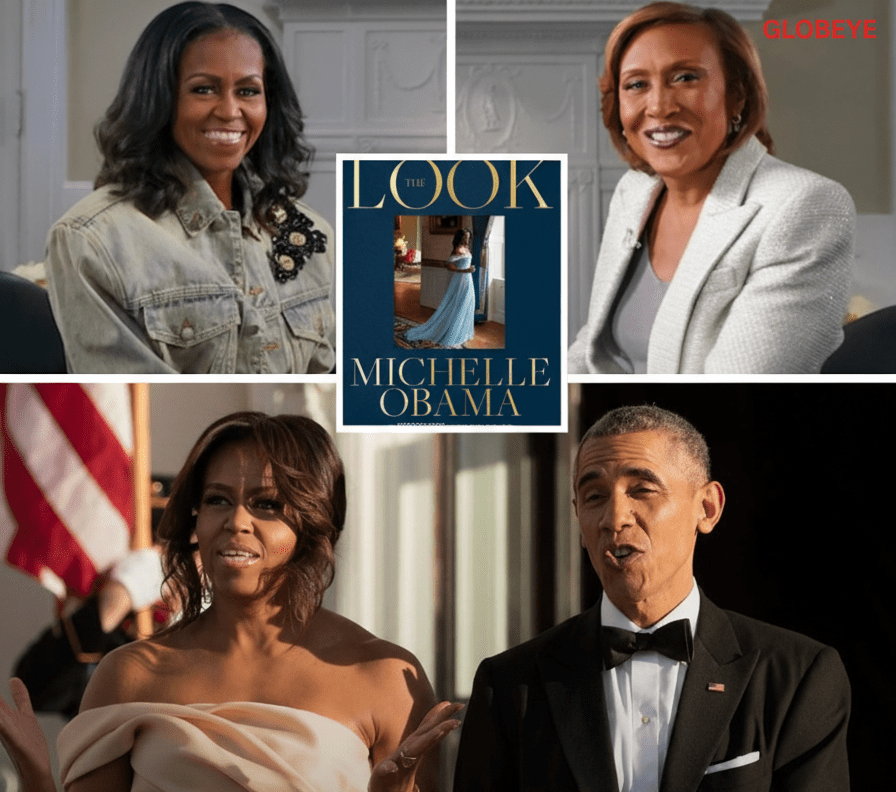

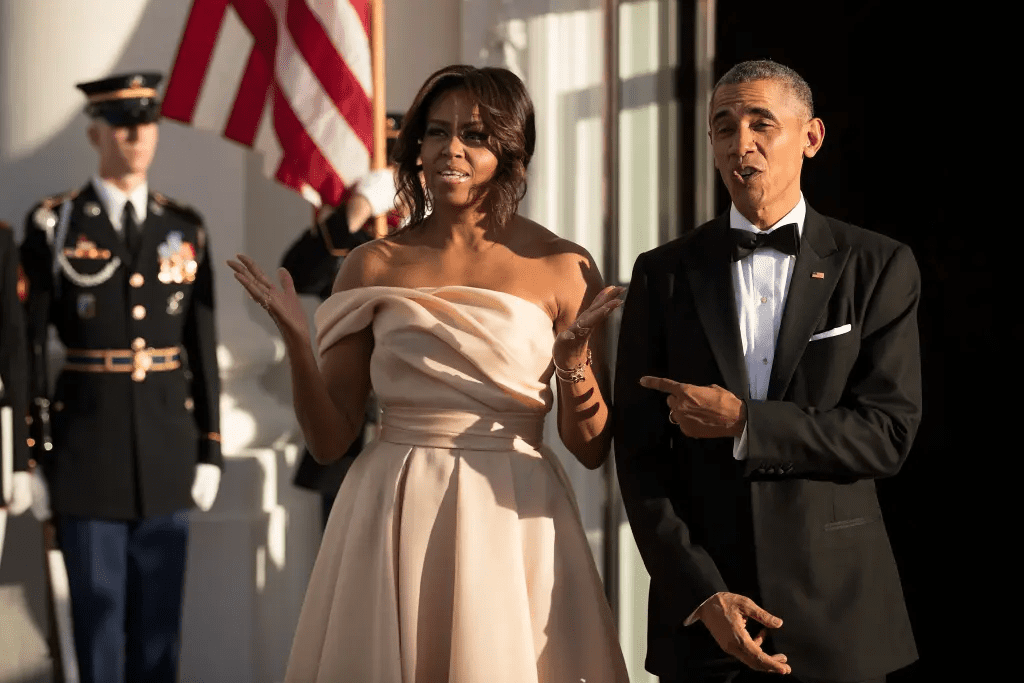

Michelle Obama Reveals the “White-Hot Glare” She Faced as First Lady and Why “We Didn’t Get the Grace” in New Book The Look

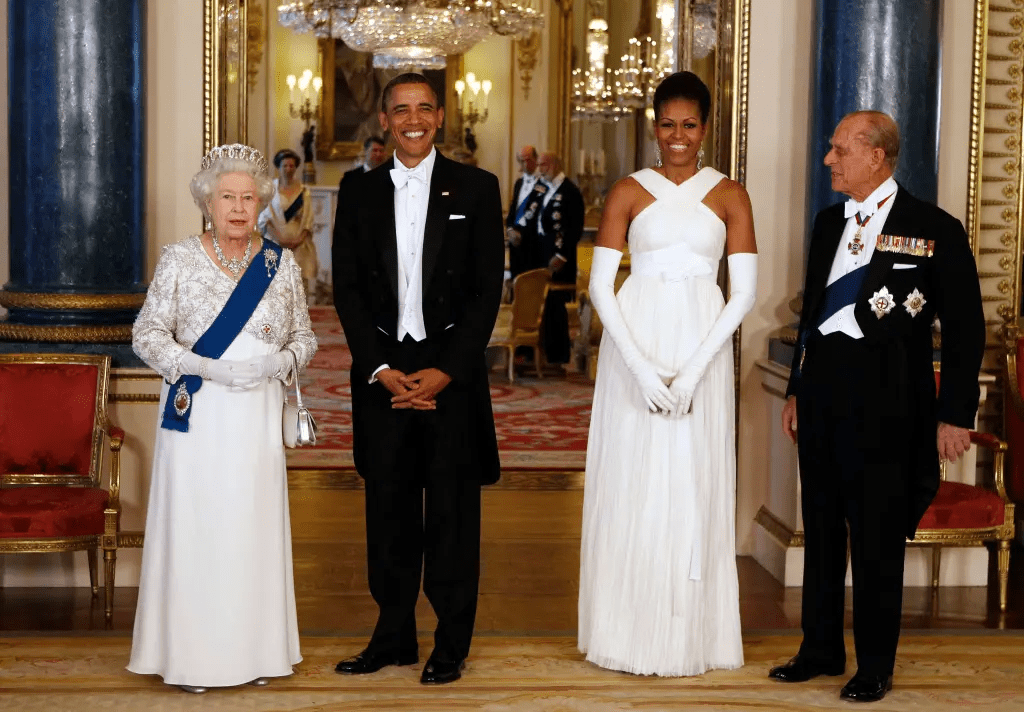

Michelle Obama stood before an audience that often saw her image but seldom heard the interior monologue of the woman behind the gowns. In her upcoming release The Look, she writes with rare clarity about the pressures of public life, the weight of representation and the scrutiny she carried as the first Black First Lady of the United States. When she reflects on her White House years, one phrase cuts sharp: “as a Black woman, I was under a particularly white-hot glare.” She writes that she and her husband were acutely aware they couldn’t afford missteps, and she notes that she and her family “didn’t get the grace that I think some other families have gotten.”

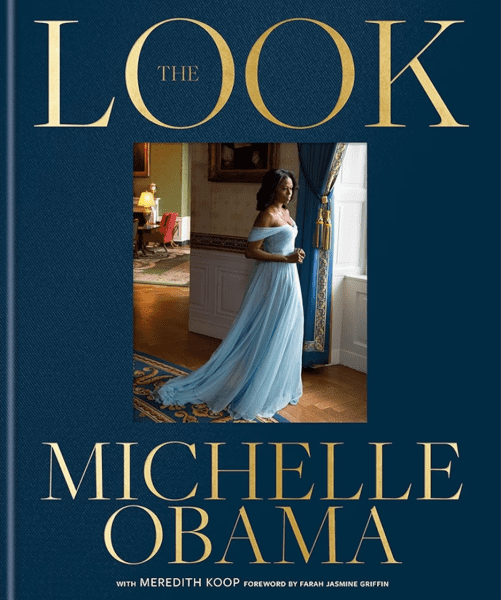

The book charts more than a decade of public transformation—campaign trail beginnings, the Senate days, arrival in 2009 to the White House, and beyond. It foregrounds how she used what she calls “soft power”—the way she showed up—with intention: architectural silhouettes, tailored jackets, bold colours or subtle refusal to conform. She explains how, behind every outfit, was a message—about her culture, her identity, her ambition, her respect for those who came before her and the younger generation she would leave behind. Yet the glare she describes was real and constant: her hair, her height, her clothing, her posture all subject to commentary, praise, dismissal or critique in ways that were uniquely magnified.

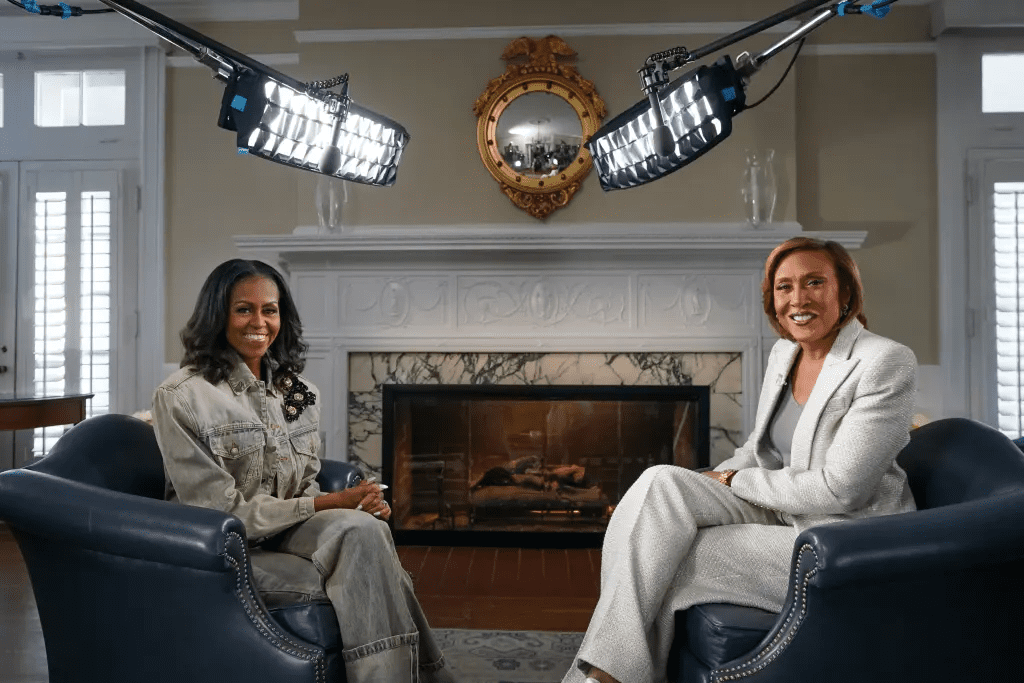

She told ABC News that when she and former President Barack Obama entered that stage, it was with full knowledge of what could happen if something went wrong. “Making a mistake in a political environment where you’re the first Black couple in the White House and people are using your race as a fear-based strategy… then everything matters,” she said. The statement traces the fine line she walked: visibility and power, yes, but with more eyes and fewer allowances. Many took her remarks as a moment of straightforward truth: The First Lady’s role is not only ceremonial—it is symbolic, heavily weighted, and deeply historic.

In The Look, she reveals how that symbol became personal. In the early years, she admits, she tried not to talk about fashion because she feared being defined by it rather than by her work. She said she asked: “Do people know me by what I do or by what I wear?” Now, in her early 60s, with daughters grown and a different kind of freedom, she embraces discussing the aesthetic — the shoes, the suits, the designers, the intention behind each appearance. “There’s something about the 60s,” she noted. “It is the best time of my life. I’m at that stage of life where I can say, ‘Yeah, maybe I know a few things.’”

Her fashion choices were never just surface-level—they were deliberate. She chose a young Taiwanese-born designer for her first inaugural gown, saw braids inserted for a portrait unveiling as a moment of affirmation, and used styling to signal for diverse designers and new voices. At the same time she contended with a designer-run First Lady lookbook, a culture that insisted on a certain type of image for the position. She writes of a tension: wanting to honour tradition while also carving space to represent modern Black womanhood, to be elegant and assertive, visible but not consumed by the appearance itself.

As a cultural icon, she had to serve multiple audiences: the fashion world that named her a triple-cover-model of Vogue, Black mothers who wanted proof someone like their daughters could sit at that desk, the world of policy wonks who sought to judge her speeches more than her shoes, and yes, a public that measured her every gesture. The glare she mentions was not metaphor alone. It was in the headlines, the blogs, the talk shows, the 24-hour commentary on the First Lady’s choices. She says that as a Black woman, the margin for error was razor-thin. Others might benefit from goodwill reserves; she felt nearly zero. “That kind of attitude blocks out opportunities,” she wrote.

Her candour has stirred conversations. Fashion critics see The Look as an exploration of identity through attire. Social-justice observers view the book as a comment on representation and racial scrutiny. Meanwhile, memory of her tenure evokes warmth, national pride, and the sense of historical significance. The phrase “white-hot glare” has emerged repeatedly in media commentary as shorthand for the intersection of race, power and visibility she confronted.

In promoting the book and its companion podcast series (titled IMO: The Look), Obama describes herself in transition: from “the First Lady” to being simply Michelle again—someone free to choose, free to express, free to reclaim the narrative of how she showed up. She writes that now, in her “golden years,” she feels more confident than ever—“settled,” as she puts it, and yet present in a different way. There’s a relaxed authority in her tone that was impossible in those first public years, when everything was scrutinised, everything was weighed.

The timing of the message matters. As the country remains divided over race, role and representation, her story speaks to more than celebrity. It speaks to how women—especially women of colour—navigate spaces historically constructed without them. It speaks to the public gaze, the assumptions of appearance, and the nested layers of identity that grow heavier when you stand in the spotlight. She offers not recrimination, but reflection. She acknowledges the past’s constraints while embracing the future’s possibilities.

Many observers see The Look not simply as a fashion memoir but as a social document. It highlights how visual presentation becomes political when the person wearing it carries meaning beyond self. It signals the way societies watch their leaders, especially when those leaders break historical molds. It reminds readers that behind the images, there were decisions—black hair worn straight or natural, a bespoke dress or a second-tier designer, a pose or a gesture. These choices mattered not just to her, but to millions who watched.

In those pages, she doesn’t ask for pity. She asks for understanding. She doesn’t paint herself as a victim but as someone who finessed her role with intention, who managed a legacy while in motion, who recognised the glare and still moved forward. Her words carry the quiet power of someone who has endured, who has learned, who has chosen to speak on her own terms. And in doing so, she invites a conversation about how we judge leaders—by what they do and how they look—and especially about how we view women and people of colour in positions of visibility.

Now, as The Look arrives and her podcast launches, Michelle Obama stands at a juncture of reflection and reinvention. The glare may have defined much of her first chapter; this book defines her next. The question she poses is subtle but profound: what happens when the world stops telling you how to show up—and you begin to show up for yourself?