Judges Approve GOP Map That Turns Swing District Red, Sparking Hopes and Heartaches for Voters in Tar Heel State

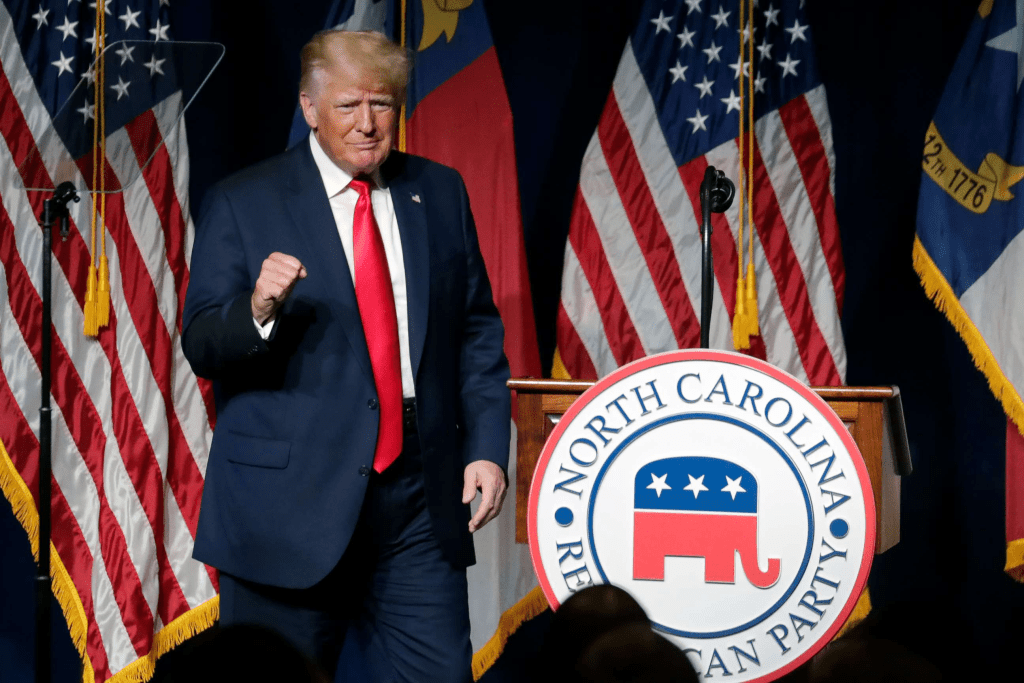

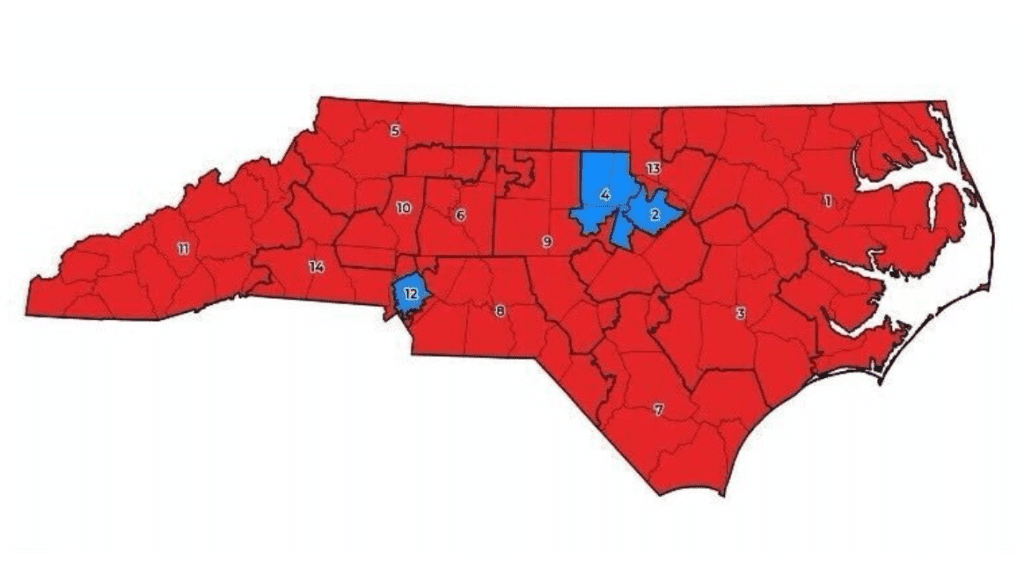

In the shadowed chambers of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina, where the hum of fluorescent lights mingles with the rustle of legal briefs, a three-judge panel delivered a decision on November 26, 2025, that redrew the political landscape of the Tar Heel State in strokes of ink and precedent. By a unanimous vote, the court upheld the Republican-controlled legislature’s newly drawn congressional map for the 2026 midterms, a reconfiguration that transforms North Carolina’s 14 districts from a balanced 7-7 partisan split into a 10-4 Republican advantage, with Democratic Rep. Don Davis’s 1st District—the eastern coastal expanse of peanut farms and fishing ports—now leaning crimson by an estimated R+5 margin. For Davis, a soft-spoken Navy veteran whose 2024 win by 1,300 votes embodied the district’s fragile diversity, the ruling landed like a quiet storm, his office in Greenville issuing a measured statement of resolve amid the weight of constituents who see their voices reshaped by lines on a map. As families in Wilson County gather for Thanksgiving leftovers and coastal towns brace for winter tides, the approval stirs a gentle undercurrent of change—a reminder that in America’s heartland, where barbecue smoke curls from backyards and church bells call across cotton fields, the boundaries of power shift not with fanfare, but with the steady hand of justice, leaving everyday lives to adapt in its wake.

The saga of North Carolina’s redistricting, a multi-year tango of census data, court battles, and partisan maneuvering, traces its roots to the 2020 count that revealed a state forever altered—population booming to 10.7 million, urban centers like Charlotte and Raleigh swelling with young professionals while rural easts clung to agricultural rhythms. Republicans, holding supermajorities in the General Assembly since 2011, seized the decennial redraw in 2021, crafting a map that packed Democratic voters into fewer districts while carving safe havens for their own, a strategy that secured 10 seats in the 2022 midterms despite Biden’s narrow 1.3 percent statewide win. Democrats cried foul, filing suit under the Voting Rights Act and state constitution, arguing the lines diluted Black voting power in the 1st District, where African Americans comprise 25 percent of the population and Davis’s coalition of farmers, teachers, and military families had flipped it blue for the first time in a generation. “This isn’t about maps—it’s about who gets to whisper in Washington’s ear,” Davis told a crowd of 200 at a Greenville community center on election night 2024, his voice rising above the clink of sweet tea glasses as supporters nodded, their faces a mosaic of pride and quiet resolve.

The litigation, a David-versus-Goliath affair in Raleigh’s echoing courthouses, spanned four years of motions, expert testimonies, and appeals that climbed to the U.S. Supreme Court before remanding back to the district level. Plaintiffs, led by the Elias Law Group and backed by the NAACP, presented maps showing the GOP plan cracking the 1st’s Black Belt communities—splitting Kinston’s majority-Black wards across lines to weaken Davis’s base—while bolstering the 6th District around Raleigh’s Research Triangle for Rep. Dan Bishop. GOP defenders, including the state’s Republican National Committee, countered with demographic analyses arguing the redraw reflected population shifts, not malice, and complied with the court’s 2023 Common Cause v. Lewis ruling that struck down prior maps for racial gerrymandering. “North Carolina’s growing, diversifying—we’re drawing fair lines for a fair fight,” Assembly Speaker Tim Moore said in a post-ruling statement, his words a nod to the 2024 census showing Hispanic populations up 20 percent in Mecklenburg County. The panel—Judges William Osteen Jr., Loretta Biggs, and James Dever—sifted through 5,000 pages of evidence, their 45-page opinion affirming the map’s constitutionality while acknowledging “close calls” on racial data. “The legislature balanced competing interests with permissible partisan goals,” they wrote, a phrase that landed like a gavel in Greenville’s coffee shops, where Davis loyalists like 62-year-old farmer Tom Wilkins sipped black brew and pondered the shift.

For Davis, the son of a sharecropper who rose from the Tuskegee Airmen-inspired 1st Congressional District to represent a swath of tobacco barns and shipyards, the ruling evokes a familiar fight—the kind etched in his Navy service aboard the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, where he learned that battles won on maps often unfold in the lives they touch. Re-elected in 2024 by 2.5 points after a grueling runoff, Davis has championed coastal resilience against hurricanes and farm subsidies for peanut growers battered by tariffs, his office a hub for veterans’ claims and flood aid. “This map changes the math, but not the mission—people in Snow Hill and Washington still need a voice that listens,” he said in a Greenville town hall on November 27, his audience of 150—a mix of Black churchgoers, white farmers, and young Latinos—nodding as he shared stories of constituents like Maria Lopez, a 45-year-old cannery worker whose family fled Hurricane Florence in 2018. Lopez, clutching a “Re-Elect Don” sign, felt the weight: “He’s the one who got our FEMA checks flowing—now, with these lines, will D.C. even hear us?” Her question hung in the humid air, a quiet echo of the district’s soul, where Gullah Geechee traditions blend with Lumbee heritage in a tapestry Democrats fear the map frays.

The redraw’s mechanics, born from the 2020 census’s 366,000-person growth spurt, reflect North Carolina’s transformation—a state where Charlotte rivals Atlanta as a banking hub and Raleigh’s tech corridor lures transplants from California. Republicans, controlling the process under the state constitution’s “partisan blind” mandate, consolidated Democratic strongholds: The 1st now stretches from Elizabeth City to Fayetteville, packing urban liberals into the 2nd while extending rural conservatism into the 6th and 13th. Analysts at the Cook Political Report project the shift nets three GOP seats, turning the 7-7 balance into 10-4, with Davis’s 1st flipping from D+3 to R+5 per FiveThirtyEight metrics. “It’s efficient gerrymandering—legal, but it silences voices in places like Kinston, where Black voters turned out big in ’24,” said election law expert Rick Hasen of UC Irvine, his analysis underscoring the map’s compliance with racial fairness tests while maximizing partisan gain. For Wilkins, whose 100-acre farm straddles the new 1st-6th line, the change feels abstract yet intimate: “My vote helped Don—now it might not count the same. It’s like redrawing your backyard fence without asking.”

Public response, from Raleigh’s legislative halls to Wilmington’s fishing piers, weaves pride with unease, a state confronting its reflection in the mirror of power. In Greenville, Davis’s district office buzzed with calls from residents like Lopez, who organized a prayer vigil at Mother Bethel AME Church, 200 voices lifting hymns for “justice in the lines.” “Don’s our fighter—he got the VA clinic open here. These maps can’t erase that,” she said, her faith a steady anchor amid the flux. Republicans, led by Moore, celebrated in a Cary presser: “Fair maps for a fair North Carolina—now we focus on jobs and schools.” Yet moderates like Rep. Richard Hudson (R-9th), whose district stays safe, urged bridge-building: “Wins are good, but let’s ensure every voice feels heard.” Social media captured the pulse: #NCRedistricting trended with 800,000 posts, from coastal Democrats sharing absentee ballot guides to rural Republicans praising “common-sense boundaries.” A viral TikTok from a Fayetteville college student, 20-year-old Jamal Reed, garnered 1.5 million views: “My vote flipped this seat blue—now it’s red? Feels like the game’s rigged before kickoff.” Reed’s frustration, echoed in PPIC polls showing 58 percent of independents wary of gerrymandering, highlights the emotional toll—a sense of disenfranchisement that lingers like humidity after a storm.

Nationally, the ruling ripples into 2026’s midterm chessboard, where Republicans defend a slim 219-212 House edge and Democrats eye flips in California and New York. North Carolina’s shift bolsters the GOP firewall, potentially shielding vulnerable freshmen like Bishop while pressuring Davis to rally a fractured coalition. “It’s a 3-seat gain on paper, but turnout tells the tale—Davis’s grassroots could defy the lines,” said Democratic strategist Jesse Ferguson, whose 2024 ground game boosted Davis by 5,000 absentee votes. For Wilkins, eyeing his soybean crop as December looms, the map stirs practical fears: “Don fights for farm bills—will the new guy’s priorities match?” His question, shared over a diner counter with fellow farmers, captures the human scale—districts not as abstract shapes, but lifelines to aid for flooded fields and trade deals for exports.

As winter’s first frost touches the Neuse River, the map’s approval settles like morning dew, temporary yet transformative. For Davis, it’s a call to the trail, door-knocking in Snow Hill where supporters like Lopez pledge their ballots. For the state, it’s a moment to reflect on representation’s fragile art—lines drawn with data, but lived with heart. In North Carolina’s wide-open spaces, where tobacco barns stand sentinel and church suppers bind communities, the redraw invites not division, but dialogue: A chance to ensure every voice, from peanut fields to Research Triangle labs, finds its place in the chorus of democracy.