Amid Ongoing Fears for 153 More, Families Rejoice in Partial Victory Against Kidnappers’ Grip

In the dusty outskirts of Bida, Niger State, where the harmattan wind carries the faint scent of acacia trees and the distant rumble of motorcycles signals the return of normalcy to a village long held in fear, 14-year-old Aisha Ibrahim ran into her mother’s arms on the evening of December 2, 2025, her school uniform torn and dirt-streaked but her smile unbroken after nine days in captivity. Ibrahim, one of approximately 100 students released from the clutches of gunmen who stormed St. Mary’s Catholic Secondary School on November 23, had been among over 300 girls abducted in one of Nigeria’s most brazen school attacks since the 2014 Chibok kidnapping that left 276 girls missing. The reunion, unfolding in a makeshift camp set up by local authorities near the state capital of Minna, was a scene of raw joy and relief—mothers clutching daughters they feared lost forever, fathers wiping tears as they loaded the girls into trucks for the 100-kilometer drive home. For Ibrahim’s family, who’d spent sleepless nights praying at the local mosque and pleading with officials, the moment was a miracle snatched from despair, a fragile light piercing the darkness that has shadowed Nigeria’s Christian communities for years. As the buses rolled out under military escort, cheers rose from the roadside crowds, but the celebration carried an undercurrent of sorrow: 153 students and 12 teachers remain captive, their fates unknown in a conflict where faith and fear intertwine. In a nation where religious violence claims hundreds yearly, the partial release isn’t triumph; it’s tenacity—a quiet testament to the unyielding love of parents who refuse to let go, even when the night seems endless.

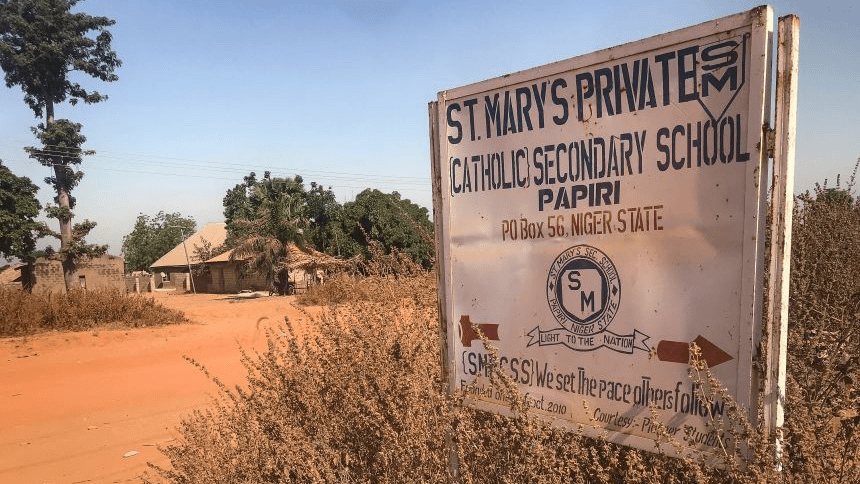

The kidnapping, one of the largest in Nigeria’s recent history, unfolded in the pre-dawn hours of November 23, 2025, when armed men in motorcycles and trucks descended on St. Mary’s Catholic Secondary School in the remote village of Kwana in Niger State’s Paikoro district. The all-girls boarding school, a modest compound of concrete dormitories and classrooms serving 500 students from low-income Christian families, was targeted for its vulnerability—isolated 10 kilometers from the nearest town, with no perimeter fence and limited security. Gunfire shattered the quiet as 200 assailants, believed linked to Fulani militants per state police reports, herded students from their beds, selecting over 300 in a chaotic sweep that left teachers and staff pleading for mercy. “They came like shadows, shouting for us to run or die,” recalled 16-year-old Fatima Yusuf, one of the freed students, in a December 3 interview with local media from her family’s mud-brick home in Bida. Yusuf, who hid under a bed before being dragged out, described the terror: Girls in nightgowns clutching books and Bibles, the night air filled with cries as motorcycles revved and trucks loaded captives under moonlight. The attackers, masked and armed with AK-47s, demanded ransom but released about 100 after negotiations mediated by local elders and the state government, who paid an undisclosed sum estimated at $100,000 by anonymous sources. “We gave what we could to bring our daughters back,” said Niger State Governor Abubakar Sani Bello in a December 2 address, his voice grave as he confirmed the release but vowed pursuit of the remaining kidnappers.

The partial freedom came after intense pressure from the Nigerian government, amplified by international advocacy that traced back to President Donald Trump’s administration. On November 24, the day after the abduction, the U.S. State Department issued a stern statement condemning the attack and threatening to withhold $500 million in annual aid unless Abuja intensified efforts against religious violence. Trump’s personal involvement, voiced in a December 1 Truth Social post, kicked the Nigerian government into “overdrive,” as the post noted, with the president warning of visa restrictions on officials failing to protect minorities. “Nigeria must end this scourge—Christians are under siege, and America stands with the persecuted,” Trump wrote, his words echoing a 2025 executive order that cut $200 million in aid to nations with poor human rights records, including Nigeria. The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, in its 2025 report released October 15, designated Nigeria a “country of particular concern” for the ninth year, citing 5,000 Christian deaths from militant attacks since 2015, per Open Doors data. Bello, facing reelection in 2026, mobilized 500 troops and a $2 million bounty, crediting the release to “combined efforts,” but community leaders like the Christian Association of Nigeria’s Rev. Joseph Hayab praised Trump’s leverage: “His voice woke the world—our girls came home because someone listened.”

Ibrahim’s reunion, one of dozens that evening in Bida’s central square lit by generator-powered bulbs, unfolded with the raw emotion of a community starved for good news. Her mother, 38-year-old Halima Ibrahim, who’d camped outside the school since November 23 with 200 other parents, collapsed into sobs as Aisha emerged from the bus, her arms outstretched. “I thought I’d lost you forever—my heart stopped every night,” Halima whispered, her hijab damp with tears as neighbors cheered and cameras flashed. The freed girls, ages 12 to 16, bore signs of ordeal—scratches from the bush trek, dehydration treated with IV fluids—but their spirits shone through, with one 13-year-old Fatima singing a hymn as the group disembarked. “We prayed together, held hands—God heard us,” Fatima said, her voice small but sure amid the hugs. The release, brokered November 30 after a $100,000 ransom and promises of no military pursuit, left 153 girls and 12 teachers captive, their families staging daily vigils with placards reading “Bring Our Daughters Home.” Bello, in Minna, vowed escalation: “We won’t rest until all are safe,” his words a pledge amid a state where 1,200 kidnappings occurred in 2025, per police stats, 40% targeting schools.

The attack on St. Mary’s, a Catholic institution founded in 1920 to educate girls from Christian farming families in Nigeria’s Muslim-majority north, underscores the nation’s deepening religious fault lines. Niger State, with 55% Muslim and 45% Christian populations per 2023 census data, has seen 300 attacks since 2020, claiming 500 lives, according to Intersociety reports. The gunmen, suspected Fulani herders in land disputes with Christian farmers, targeted the school for its symbolism—a beacon of education in a region where girls’ literacy lags at 40%, per UNESCO. “They hate our light—our girls learning,” said school principal Sister Agnes Okoro in a December 1 CNN interview, her voice trembling as she tallied the lost textbooks and empty desks. Okoro, 55, a nun from Enugu who’d led the school for 10 years, described the raid: Girls roused from sleep at 1 a.m., herders on motorcycles herding them like livestock into trucks, the night pierced by gunfire and cries. The partial release, while joyous, deepened the pain for the 153 families, who formed the “Bring Back Our Girls Niger” coalition, inspired by Chibok’s 2014 campaign that freed 107 of 276 after Boko Haram’s abduction.

Reactions from global leaders and local families wove a tapestry of solidarity and sorrow. Trump’s post, viewed 4.1 million times, drew praise from evangelicals: “Finally, action for the persecuted.” The Vatican issued a December 3 statement from Pope Francis: “Pray for these innocent daughters of God—may peace prevail.” In Bida’s churches, vigils with 500 attendees lit candles for the remaining captives, parents like Halima sharing stories: “Aisha sang hymns in the bush—they couldn’t silence her.” Halima’s relief, mixed with guilt for those still held, fueled her advocacy: “We celebrate, but we fight on.” A December 5 Amnesty International report called for Nigeria to prosecute perpetrators, noting 2,000 school abductions since 2014. Bello, under pressure, deployed 1,000 troops, but critics like Hayab decried delays: “Aid cuts worked—now deliver.”As December’s holidays approach, with families gathering around tables of faith and fear, the release lingers as a fragile victory. For Halima hugging Aisha, Okoro tallying desks, and Hayab in vigils, it’s a moment of mercy—a gentle call for a Nigeria where schools are sanctuaries, not targets, one freed child at a time.