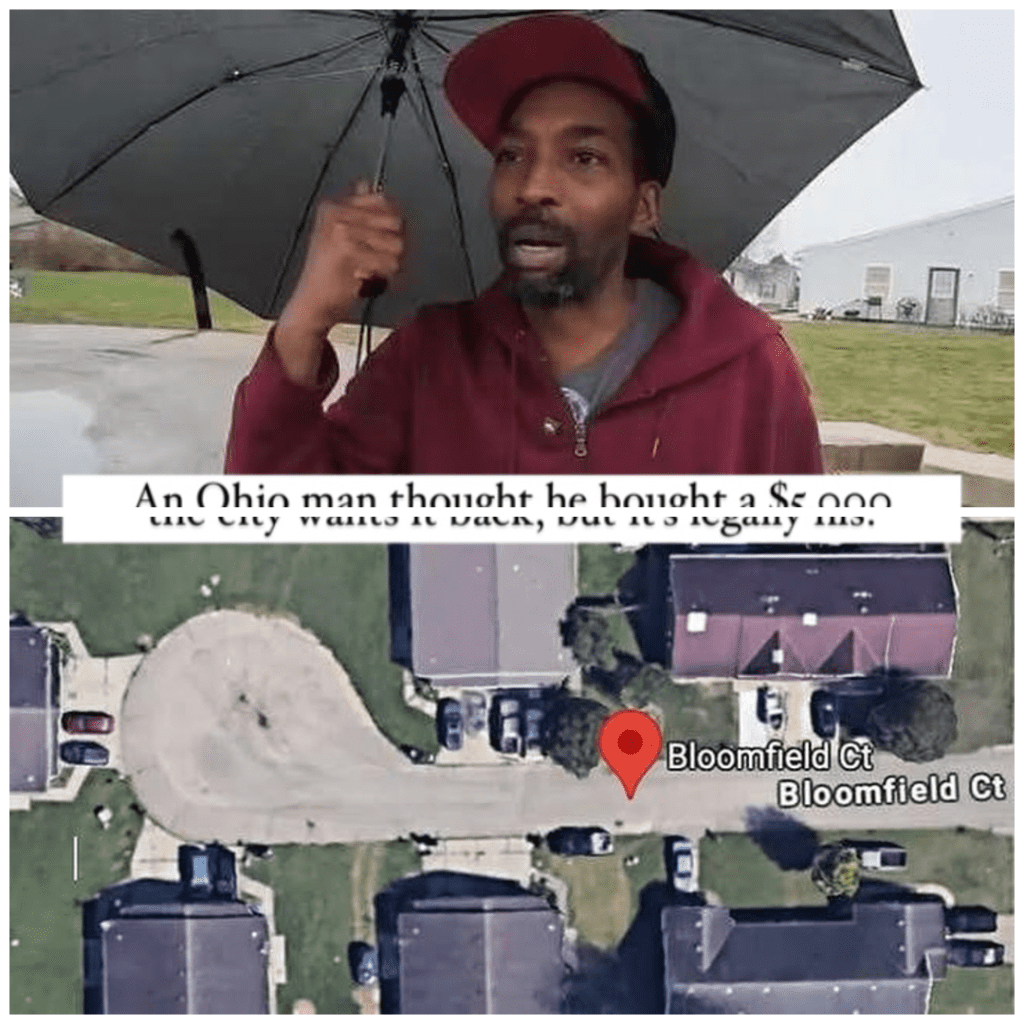

He Thought He Bought a Vacant Lot to Build a Home—But Ended Up Owning an Entire Street, Houses and All, and Now the City Wants It Back

It started as what seemed like a simple and hopeful decision. Jason Fauntleroy, an Ohio man with plans to build his dream home, purchased what he believed to be a vacant lot through a sheriff’s sale in Butler County. He paid $5,000 for the parcel, imagining blueprints, a new beginning, and the satisfaction of homeownership. What he didn’t expect was that his purchase came with much more than grass and soil. As the paperwork settled and reality took shape, Fauntleroy realized he hadn’t just bought a lot—he had accidentally bought an entire street. And not just the pavement, but the infrastructure, the easements, and the legal responsibilities tied to it. A whole cul-de-sac, complete with homes already occupied by residents.

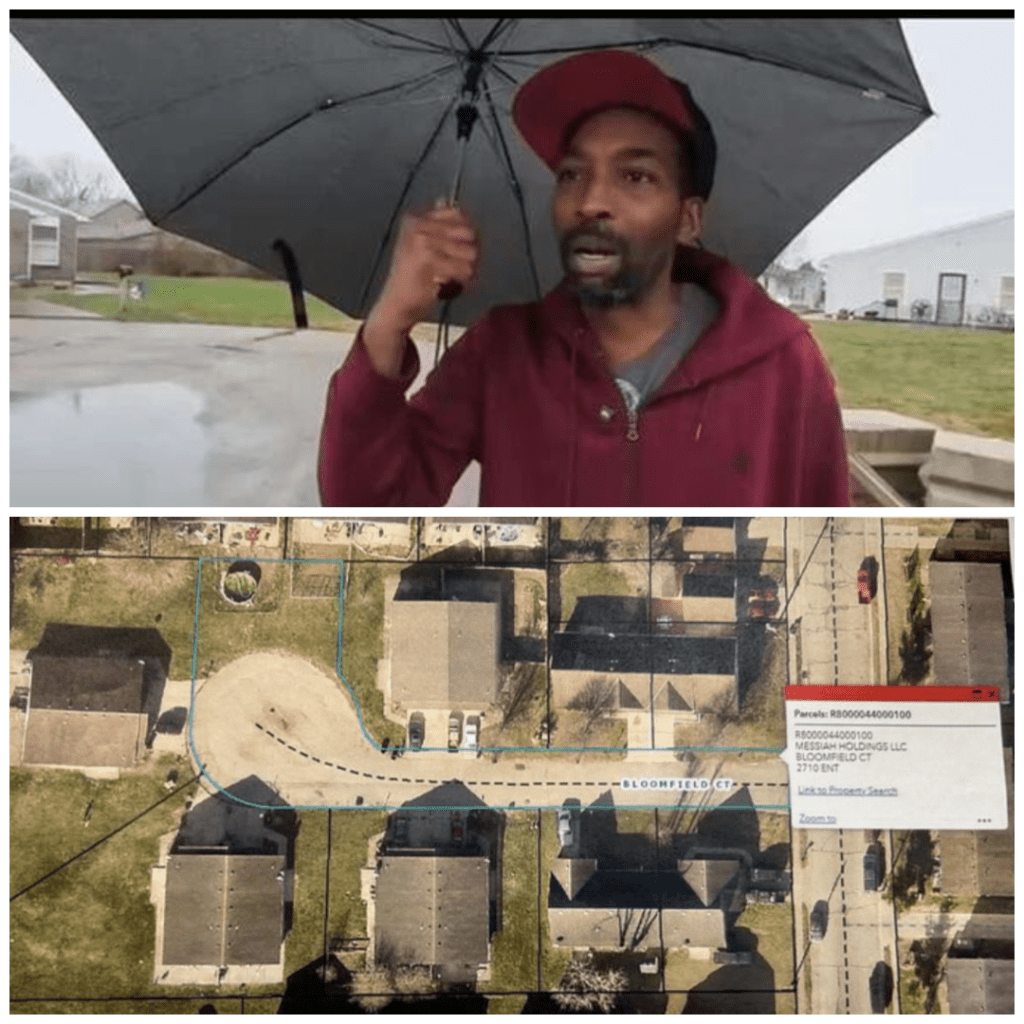

The street, Bloomfield Court, is tucked into a quiet subdivision in the city of Trenton. The five homes along the curved cul-de-sac sit peacefully, with driveways, mailboxes, and trimmed front yards. But unbeknownst to the residents, the legal title to their street had transferred to a man who thought he’d just bought a single patch of land to build on. It’s the kind of twist that would sound outrageous in a sitcom, but it’s very real—and it has sparked a legal and ethical debate that’s now dragging the city into a complex and public controversy.

When Fauntleroy first realized what he had actually purchased, he says he was shocked. At first, there was confusion—how could something so enormous have been misrepresented so simply? But then came the even stranger part: despite the obvious mistake, the purchase was legally sound. The documents were signed, the payment was processed, and the title was transferred. As far as the law was concerned, Bloomfield Court now belonged to Jason Fauntleroy.

That realization opened a can of worms. Legally owning the street meant Fauntleroy was now responsible for its maintenance, property taxes, and insurance. It also meant the residents of the five homes on that street were technically driving, parking, and living on private property that belonged to him. In theory, he could have blocked access, charged tolls, or taken drastic action—but he didn’t. Fauntleroy says he didn’t want to cause trouble. He wanted clarity. He wanted the city to step in, acknowledge the mistake, and work out a fair resolution.

But instead, things got worse. According to Fauntleroy, the city of Trenton refused to communicate with him in good faith. He said officials ignored his emails and calls, and when they did respond, it was to initiate eminent domain proceedings—effectively trying to take the property back without proper compensation. The city reportedly offered payment based only on the original lot’s appraised value, not on the value of the entire street or its strategic significance. Fauntleroy wasn’t just disappointed. He was angry.

In media interviews, he called the experience a nightmare. Not because he didn’t want to own the property, but because the city acted as though he didn’t matter. He described feeling shut out, disrespected, and steamrolled by a bureaucracy that refused to acknowledge the unique reality of the situation. All he wanted was a fair deal, a conversation, and recognition that what he now owned had genuine legal and monetary value.

The city, on the other hand, says Bloomfield Court was originally meant to be privately maintained by a now-defunct homeowner’s association. They argue that it was never intended to fall into private ownership outside of the subdivision. Their goal is to convert the street into a public road, which would shift maintenance responsibilities back to the city. But in their rush to resolve what they view as a clerical mishap, they underestimated the personal and legal implications of trying to take land away from someone who bought it, however unintentionally, by the book.

At the heart of this dispute is a conversation about property rights, public accountability, and the unintended consequences of automated systems. Sheriff’s sales are notorious for having confusing or incomplete listings, often due to the nature of foreclosure paperwork and overlapping land records. Most buyers approach them with caution, knowing the risks. But what happens when the system works perfectly on paper and still produces a mistake this large?

Ohio law requires that any property taken under eminent domain must be appraised and compensated at fair market value. Fauntleroy argues that this process hasn’t happened. The city is treating his ownership as an inconvenience rather than a transaction, and he wants a jury trial if that’s what it takes to protect his rights.

Meanwhile, residents of Bloomfield Court are caught in the middle of a situation they never saw coming. Most had no idea their street wasn’t publicly owned. They’ve continued their routines—commuting to work, walking their dogs, hosting guests—never knowing the land beneath their tires and lawns now belonged to someone new. Some have expressed concern, others confusion, but all agree on one thing: this could have been handled better.

For Fauntleroy, the experience has been draining. What started as a dream—a simple desire to build a home—has turned into a legal battle with no easy answers. He never wanted to own a street. He didn’t plan to become a symbol of municipal dysfunction. But now that he’s here, he’s not backing down. He believes in fairness, in transparency, and in being treated like a person instead of a problem.

This case is more than a quirky headline. It’s a mirror held up to the systems we trust, the institutions that shape our communities, and the fragile line between public and private life. Jason Fauntleroy may have bought a street by accident, but his fight to keep it—or to be compensated fairly—might just set a precedent for what happens when real estate, red tape, and real people collide.