In a Landmark Ruling, the Constitutional Tribunal Dissolves a Fringe Group, Evoking Ghosts of Oppression as Survivors and Youth Grapple with the Legacy of Loss

In the grand, vaulted chambers of Warsaw’s Constitutional Tribunal, where the weight of Poland’s hard-won democracy hangs as palpably as the chandeliers above, Judge Krystyna Pawłowicz delivered a verdict on December 3, 2025, that resonated like a long-suppressed sigh across a nation scarred by the 20th century’s darkest chapters. “There is no place in the Polish legal system for a party that glorifies criminals and communist regimes responsible for the deaths of millions of human beings, including our compatriots, Polish citizens,” she declared, her voice steady amid the rustle of legal briefs and the click of cameras. The ruling dissolved the Communist Party of Poland (KPP), a marginal group with roots in the post-1989 thaw, deeming its ideology fundamentally at odds with the constitution’s explicit ban on totalitarian promotion. For the handful of KPP members—estimated at under 1,000, their red banners more relic than rally—the decision meant erasure from the political register, a quiet end to a fringe voice that had drawn scant votes but stirred deep unease among those who remember bread lines and secret police knocks. As the gavel fell, outside in the crisp December air, elderly survivors of the Soviet era wiped tears under overcast skies, their whispers mingling with the city’s holiday bustle—a poignant reminder that for Poland, freedom isn’t abstract; it’s the fragile fruit of lives reclaimed from the shadows of gulags and uprisings.

The KPP’s dissolution caps a five-year legal odyssey that began in 2020, when then-Minister of Justice Zbigniew Ziobro petitioned the tribunal, arguing the party’s program echoed the very totalitarianism Article 13 of the 1997 Constitution forbids. That article, etched into Poland’s post-communist Magna Carta, stands as a bulwark against the ghosts of Nazi and Soviet horrors, prohibiting parties “aimed at the violent overthrow of the constitutional order” or promoting ideologies that once devoured generations. The KPP, founded in 2002 as a self-proclaimed heir to Marxist ideals, had always hovered on the edges—its manifestos praising workers’ rights and anti-capitalism, but laced with nostalgia for the Polish United Workers’ Party that ruled from 1948 to 1989. Critics, including Holocaust survivors and Solidarity veterans, pointed to events like the party’s 2019 May Day marches, where red flags waved alongside chants that romanticized the era of Stalinist purges and the 1956 Poznań protests crushed by tanks. “They wave symbols of chains as if they were keys,” one Warsaw retiree, a former shipyard worker, told local reporters after the ruling, his hands trembling as he clutched a faded Lech Wałęsa poster from the 1980s.

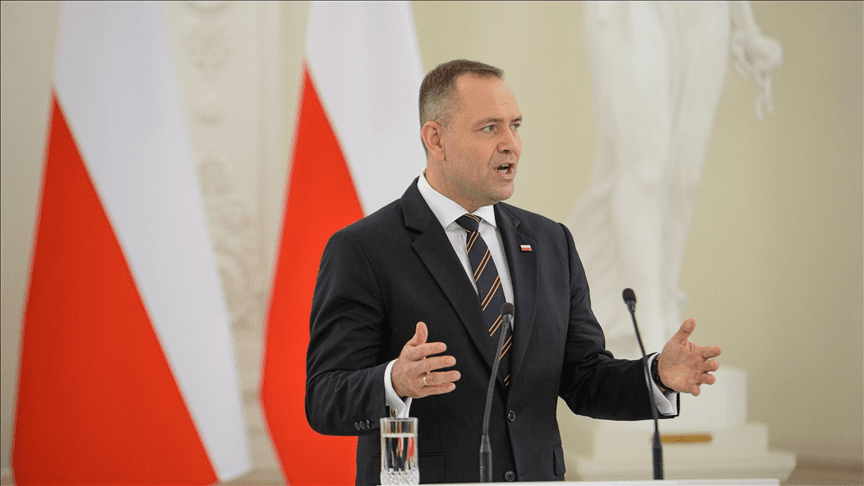

Pawłowicz’s justification, read in a session chaired by President Bogdan Święczkowski, wove history with law in a tapestry of remembrance. The tribunal, a body often criticized for its ties to the former Law and Justice (PiS) government, merged Ziobro’s petition with a fresh one from President Karol Nawrocki in November 2025, who argued the KPP’s activities “contradict the legal order of Poland.” Unanimous in its 15-0 decision, the panel cited the party’s praise for Soviet invasions—like the 1920 “Miracle on the Vistula” reframed as liberation—and its alignment with regimes responsible for the Katyn Massacre, where 22,000 Polish officers were executed in 1940. “This isn’t suppression of ideas; it’s safeguarding the democracy bought with blood,” Pawłowicz emphasized, her words a bridge to the 1989 Round Table Talks that birthed modern Poland. The ruling orders the party’s removal from the National Electoral Commission register, freezing assets and barring members from forming successors for at least five years—a measure designed to prevent phoenix-like revivals.

For Poles of a certain age, the ban evokes a flood of memories, bittersweet and unbidden, from the gray dawn of communist rule. In Kraków’s Nowa Huta steelworks district, where Stalinist blocks still stand as monuments to forced industrialization, 82-year-old Zofia Kowalska lit a candle at a small home altar on the evening of the ruling, her arthritic fingers tracing a photo of her brother, arrested in 1953 for “anti-state agitation” and never seen again. “We whispered in cellars, dreamed in code—now, to see their symbols banned feels like closing a wound that’s never healed,” she shared with a local journalist, her voice soft against the clink of rosary beads. Kowalska’s story mirrors thousands: The Polish People’s Republic, imposed after Yalta’s partitions, saw 100,000 political prisoners by 1956, per Institute of National Remembrance archives, and economic plans that starved the spirit if not always the body. The 1970s Gdańsk strikes, quelled with bullets, birthed Solidarity’s flame, but the scars linger in family lore—lost jobs, silenced poets, bread rationed while elites dined on caviar.

Younger generations, born after 1989’s velvet revolution, absorb the news through a lens of education and echo. In Warsaw’s Jagiellonian University cafes, where students huddle over laptops amid steam from pierogi pots, 22-year-old history major Lena Nowak scrolled the tribunal’s press release during lunch, her brow furrowing. “My grandparents fled the draft to the West—communism’s a museum piece to me, but banning it? It feels like erasing debate,” she said, sipping black tea as friends nodded. Nowak’s ambivalence reflects a Poland transformed: GDP per capita tripled since EU accession in 2004, unemployment at 5%, yet nostalgia flickers in polls—10% of under-30s view the old regime fondly for its social safety nets, per a 2024 CBOS survey. The KPP, with its 0.1% vote share in 2023 locals, was no threat electorally, but symbolically potent: Its 2024 rally honoring Stalin’s birthday drew 200, sparking protests from groups like the Never Again Association, which monitors fascist and communist revivals.

The ruling’s ripple reaches Brussels, where EU watchdogs eye Poland’s tribunal—a body reformed under PiS to include judges like Pawłowicz, a former far-right MP accused of bias in 2023 Article 7 proceedings. The European Commission, in a December 4 statement, welcomed the ban as “consistent with democratic norms” but urged transparency in judicial appointments, a nod to ongoing rule-of-law funds frozen at €35 billion since 2021. Nawrocki, a historian elected in 2025 on a platform of “memory politics,” celebrated the decision as “justice delayed but not denied,” tying it to his push for de-communization laws expanding bans on Soviet monuments. Critics, including leftist MEP Robert Biedroń, called it “a step backward for pluralism,” arguing fringe voices deserve space in debate, not dissolution—a view echoed in a November 2025 international statement from 20 communist parties condemning the petition as “fascist repression.”

Public sentiment in Poland tilts toward quiet approval, a collective exhale from a nation that lost 6 million in World War II, half its prewar population, under regimes the KPP’s ideology romanticized. In Gdańsk’s shipyards, where cranes now build LNG terminals instead of warships, tour guides like Marek Wiśniewski pause mid-story for visitors. “Solidarity started here because we refused to glorify chains—today’s ruling honors that refusal,” he said on December 4, gesturing to the monument etched with 1980 strike demands. Wiśniewski, whose father was a shipwright beaten in 1970, sees the ban as closure: “Not hate, but healing—for the young who don’t know the fear.” Social media buzzed with 1.5 million #KPPBan posts, blending survivor testimonies—”My uncle vanished in ’56; this is for him”—with youth memes juxtaposing red stars with EU blue flags. A CBOS flash poll showed 68% support, highest among over-50s at 82%, but dipping to 55% among urban millennials wary of slippery slopes.

For the KPP’s remnants—activists like party chair Józef Łukaszewicz, a Warsaw retiree who joined in 2005 seeking “workers’ dignity”—the loss stings with finality. “We spoke for the forgotten, not the tyrants,” Łukaszewicz told TVN24 post-ruling, his voice cracking as he boxed party literature in a cramped apartment lined with Lenin portraits. With 500 members scattered across factories and universities, the group plans appeals to the European Court of Human Rights, citing Article 11 freedoms. “Banning ideas doesn’t kill them—it martyrs them,” he added, echoing dissidents who once smuggled samizdat under Soviet eyes.

As Warsaw’s Christmas markets twinkled that evening, mulled wine steaming under strings of lights, the ruling settled like fresh snow—covering old wounds while inviting reflection. For Kowalska with her candle, Nowak over her tea, and Wiśniewski at his tours, it’s a chapter closed on glorification, opened on remembrance. In Poland’s resilient s