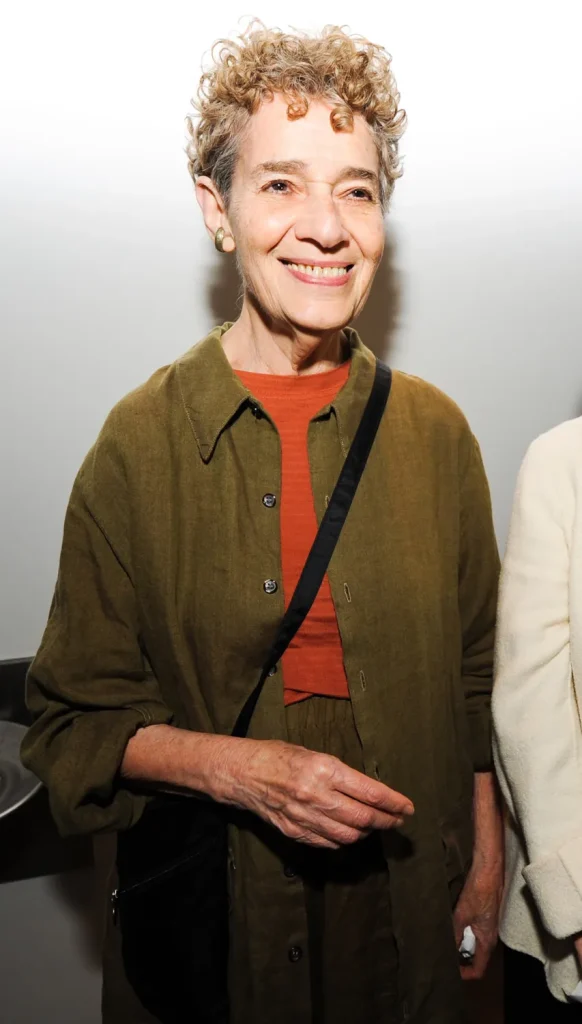

Acclaimed Sculptor Jackie Ferrara Ends Her Life Through Medical Aid in Dying Despite Being in Good Health, Leaving Behind a Legacy of Artistic Independence

Jackie Ferrara, one of America’s most distinctive sculptors, has died at 95 after choosing to end her life through medical aid in dying. Known for her monumental wood structures and geometric works that transformed public spaces, Ferrara’s decision has sparked reflection, not only on her life and art but also on what it means to face death on one’s own terms.

Ferrara’s estate and legacy adviser, Tina Hejtmanek, confirmed that the artist passed away peacefully on October 22. What makes her story extraordinary is that Ferrara, by all accounts, was still in relatively good health. She had not been battling a terminal illness nor suffering from acute physical decline. Instead, she made a deliberate choice — one that aligned with the independence and control that defined her both as a person and as an artist.

Born in Detroit in 1929, Jackie Ferrara came of age in a postwar art world dominated by male voices, yet she carved a space entirely her own. Her sculptures, often built from stacked wooden planks and precise architectural forms, blended the mathematical with the meditative. Her works are part of major museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, and many of her site-specific installations remain permanent fixtures across the United States.

To those who knew her, Ferrara’s art mirrored her personality — meticulous, thoughtful, and quietly rebellious. She rejected convention at every stage of her career. In a time when abstraction and conceptual art reigned, she pursued structure, symmetry, and materiality, always finding beauty in simplicity. Friends recall her work ethic as tireless, her curiosity boundless. Even in her later years, Ferrara continued to visit studios and galleries, discussing design and material choices with the same clarity and energy she had in her youth.

Her final decision — to use medical aid in dying — reflects that same sense of agency. Legal in several U.S. states under strict criteria, the practice allows individuals facing unbearable suffering or an irreversible decline in quality of life to choose when and how to end their lives. In Ferrara’s case, however, her decision did not stem from pain or fear. According to those close to her, it came from a belief in autonomy — the idea that life, and by extension death, should be guided by personal choice.

“She didn’t want life to make the decision for her,” Hejtmanek said in a statement. “She wanted to make it herself — and that’s exactly what she did.”

The art community has responded with both sadness and respect. Tributes have poured in from museums, galleries, and fellow artists who described her as a pioneer whose creative courage inspired generations. Many have noted the poetic symmetry of her final act — the same precision, control, and intentionality that defined her sculptures also shaped the way she exited the world.

Ferrara’s work was never about spectacle. It was about presence — the quiet dialogue between materials and space, between human perception and the permanence of form. In that sense, her death feels like an extension of her philosophy. She leaves behind not only a lifetime of art but also a profound conversation about dignity, freedom, and the right to live — and end — on one’s own terms.

Jackie Ferrara’s influence continues through her public installations and museum pieces, where her work invites the same contemplation she once did in person: how structure and humanity intertwine. Her passing reminds us that the truest art form may be the courage to create and the grace to choose when to let go.