Gunmen Storm Nigerian Catholic School, Snatching 52 Children in Dead of Night

In the pre-dawn hush of Papiri, a remote village in Nigeria’s Niger State where the harmattan wind whispers through baobab branches like a mother’s lullaby, the first screams shattered the stillness at 2 a.m. on November 21, 2025. At St. Mary’s Catholic Secondary School, a modest boarding haven for 52 children aged 12 to 17, the night was meant for dreams—of exams aced, futures forged, soccer fields conquered under equatorial suns. Instead, it became a nightmare etched in gunfire and fear, as masked gunmen burst through the gates, their AK-47s glinting in the moonlight like scythes of fate. The raiders, clad in black and moving with the ruthless precision of shadows, rounded up the sleeping students from their dorms, herding them like frightened lambs into the darkness, leaving behind a security guard crumpled and bleeding from a point-blank shot. For the families who awoke to frantic calls from the school—sobs of “Mama, they’re taking us!” crackling over spotty lines—the abduction wasn’t just theft; it was a tearing of the soul, a fresh wound in a nation where the faithful, particularly Christians, have become prey in a relentless hunt that defies the world’s weary gaze. As rescue teams scramble through the scrubland and prayers rise from cathedrals across the globe, the Papiri raid stands as a searing indictment of Nigeria’s unraveling, where innocence is the ultimate casualty in a conflict that claims lives and legacies with chilling indifference.

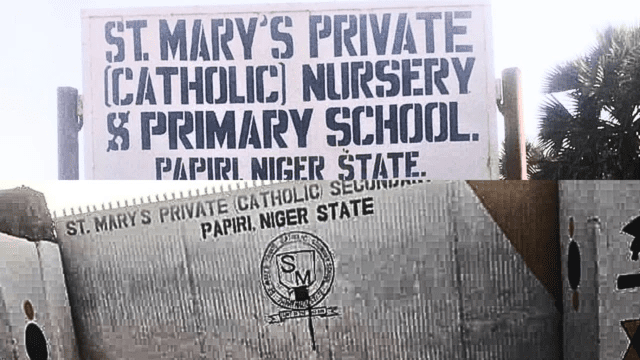

The assault on St. Mary’s unfolded with the brutal efficiency that’s become tragically routine in Nigeria’s northwest, a region where banditry and extremism blur into a fog of fear that engulfs villages like Papiri. The school, a Catholic outpost in Agwara Local Government Area, serves as a beacon for 200 students from farming families who trek miles for lessons in math and morals, its whitewashed walls a symbol of hope amid the red earth and relentless poverty. Early Friday, as the clock struck 2, the gunmen—estimated at 20 strong by initial survivor accounts—scaled the perimeter fence, their boots silent on the dew-kissed grass. “They came like ghosts, shouting in Hausa for us to lie down,” recounted 15-year-old Fatima Yusuf, one of the few who escaped by hiding under her bunk, her voice a fragile thread in a phone interview with local outlet Daily Post Nigeria, her pajamas still clutched in trembling hands. Fatima, whose father tends millet fields on the village outskirts, peered through slats to see classmates dragged from beds, some in nightgowns, others barefoot and bewildered, the air thick with cries and the acrid tang of cordite from warning shots. The security guard, 52-year-old Baba Musa, lay wounded in the dirt, his radio smashed, his pleas for mercy met with a bullet that left him fighting for life in a Minna hospital, his family gathered at his bedside with rosaries wrapped around white-knuckled fists.

Word spread like wildfire through Papiri’s thatched roofs and mud-brick homes, parents bolting from sleep to the school’s compound, where the headmaster, Father Ignatius Okonkwo, stood pale and prayerful amid the chaos. “They took our light—52 souls, gone in the night,” Okonkwo told reporters from the Catholic Diocese of Kontagora, his cassock rumpled from the night’s vigil, his eyes red-rimmed from unshed tears. The diocese, in a memo signed by Secretary Jatau Luka Joseph, condemned the raid as “an assault on innocence and faith,” confirming abductions of students, teachers, and the guard, the attack spanning 1 a.m. to 3 a.m. in a blitz that left classrooms in disarray and hearts in tatters. Niger State Police, in a statement from Commandant Shawulu Danmamman, mobilized tactical units and military reinforcements, vowing “immediate rescue operations” through the thorny bushlands where bandits vanish like smoke. But for the families clustered in the school’s chapel, clutching photos of wide-eyed teens in school uniforms, vows ring hollow against the echo of absence—breakfast tables set for 52 empty chairs, schoolbags slung over shoulders that won’t return.

This Papiri predawn pillage isn’t an isolated outrage; it’s the latest laceration in a hemorrhage of horror that’s bled Nigeria for decades, a nation where Christianity—the world’s most persecuted faith, touching 380 million believers per Open Doors’ 2025 World Watch List—faces its fiercest fire on African soil. Ranked sixth globally for Christian persecution, Nigeria has seen 3,100 believers slain for their faith in the past year alone, a toll that dwarfs all others, with Fulani militants, Boko Haram splinter ISWAP, and shadowy bandits blending banditry with bigotry in raids that raze villages and reap souls. In 2024, over 5,000 Christians fell to Islamist violence, per Intersociety tallies, their churches torched in Plateau State’s Christmas massacres and homes hacked in Benue’s bush wars, a pattern that surged under former President Muhammadu Buhari’s watch and lingers under Bola Tinubu’s tenure. The Papiri kidnapping, coming days after 25 girls snatched from a Kebbi school, fits the fatal formula: schools as soft targets, children as currency in a ransom racket that nets $10 million annually, but laced with the lethal intent to erase the faithful. “It’s genocide by increments,” whispers Rev. Matthew Hassan Kukah, Catholic Bishop of Sokoto, his voice a velvet veil over volcanic grief in a BBC interview, his diocese scarred by 200 killings in 2024. “They don’t just take lives—they take futures, faith by faith.”

For Fatima’s mother, Aisha Yusuf, 38 and widowed since her husband’s 2023 field slaying, the abduction is a dagger to the heart already pierced by loss. “My girl is all I have left—she sings hymns in the mornings, dreams of nursing like her auntie,” Aisha says, her hijab framing a face furrowed by fear, gathered with other mothers in Papiri’s makeshift command post, a tent strung with rosaries and ransom-ready naira. Aisha, a maize farmer whose fields feed the village but barely her belly, scraped for Fatima’s tuition, the school’s scholarship a slender thread of hope. Now, that thread snaps, the bandits’ demand—rumored at 50 million naira ($30,000)—a fortune that could bankrupt her kin. “God sees our tears,” she prays, her hands clasped around a faded photo of Fatima in her school smock, the girl’s smile a sunbeam in the storm. Across Nigeria’s north, 3.5 million displaced by such depredations huddle in IDP camps, their children schooled in tents or not at all, the cycle of violence a vicious loop where education is enemy number one. Boko Haram’s name—”Western education is forbidden”—isn’t hyperbole; it’s holy writ, their 2014 Chibok kidnapping of 276 girls a blueprint echoed in Papiri’s predawn panic.

The global groan is a chorus of condemnation, from the Vatican’s somber statement—”The Holy Father prays for the swift return of these innocents”—to the U.S. State Department’s “deep concern” and EU calls for Nigerian action. Open Doors, the Dutch watchdog whose 2025 list ranks Nigeria sixth for Christian woe, tallies 3,100 faith-fueled fatalities last year, a drop from 4,118 in 2024 but still a deluge that drowns the Delta, with Fulani herders’ raids claiming 1,100 in Benue alone. “It’s not banditry—it’s belief-driven brutality,” says Intersociety’s Emeka Umeagbalasi, his Lagos office a warren of reports charting 7,087 Christian deaths in 2025’s first eight months, an average 30 souls a day. Umeagbalasi, a human rights hound whose tallies trace from eyewitnesses to ecclesiastical ledgers, decries government complicity: “Military infiltrators tip off militants; it’s a culture of death cloaked in corruption.” Tinubu, in a November 21 address, vowed “decisive force,” canceling trips to Angola and South Africa to command the counterstrike, but for Aisha, vows are vapor—her Fatima, one of 52 snatched souls, a statistic that steals sleep and sanity.

Rescue glimmers in the grit of ground teams, Niger Police’s tactical squads scouring scrub with drones and dogs, their Humvees kicking dust through villages where tips trickle from terrified tongues. Past hauls—like the 2024 Kuriga rescue of 137 Bethel students—offer flickers of hope, ransoms paid or paths traced through herder networks. But for Fatima’s fatherless family, hope is a fragile flame—prayers in the mosque mingling with pleas to patrons, the village pooling poultry and pesos for the payout. “Bring my light back,” Aisha whispers to the dawn, her fields fallow for the first time in fear. Across the Atlantic, in cathedrals from Chicago to Cape Town, vigils veil the void, candles flickering for the 52 stolen stars of St. Mary’s. Kukah, the Sokoto shepherd whose sermons stir souls, calls it “genocide’s quiet quarter”—not state-sponsored slaughter, but systemic silence that lets militants multiply, their AKs funded by ransoms and rustling.