Supreme Court Clears Way for Trump to Remove Democratic FTC Commissioner—A Stunning Shift from 1935 Precedent

I kept thinking about how one ruling can change everything—not just policy, but how a generation understands what power means. Today’s news about President Trump’s ability to remove a Democratic member of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reminded me of that.

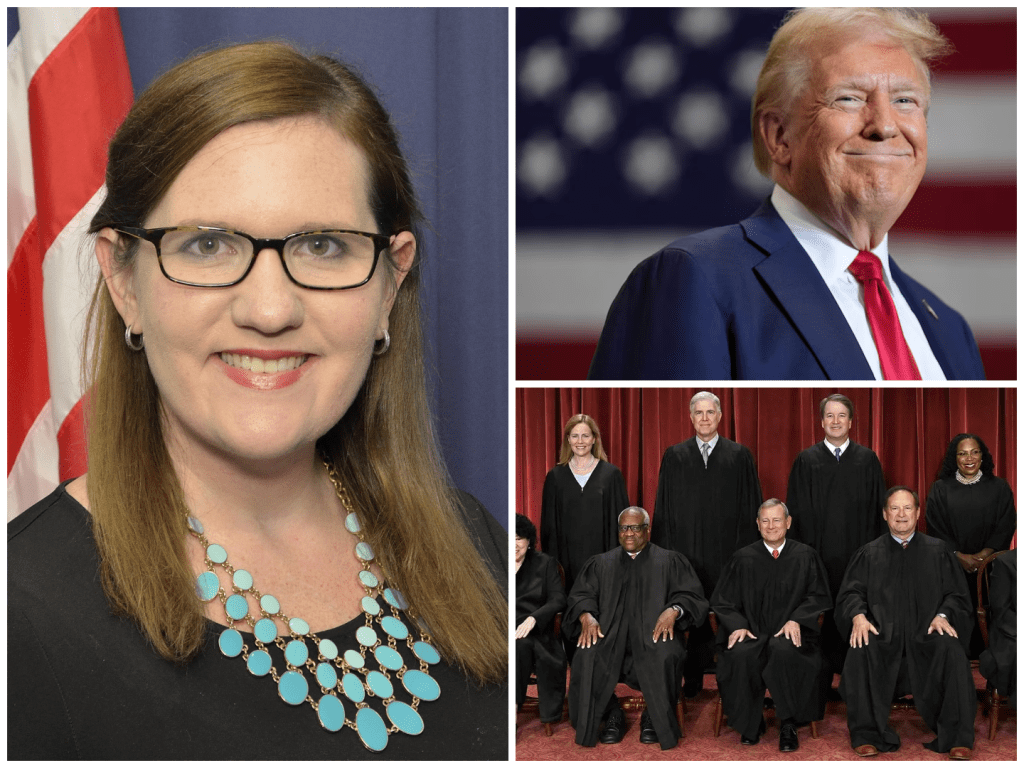

The moment broke with an almost electric buzz: Chief Justice John Roberts granted an interim stay, allowing Trump to move forward—for now—with firing Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter. It’s not the end of the legal fight, but it’s a powerful pivot. The move reverses long-standing tradition rooted in the 1935 Supreme Court case, Humphrey’s Executor, which for decades has shielded independent federal commissioners from being removed without cause. Now, as appeals continue, that protection feels shaky.

Reading the headlines, I found myself thinking back to what the court once stood for in that 1935 decision. Back then, President Franklin Roosevelt was frustrated that he couldn’t control the FTC—because the Commission had authority rooted firmly in Congress’s intent to remain independent. Humphrey’s Executor became a cornerstone, preserving an agency’s ability to act without fear of arbitrary removal. That principle has been woven into the fabric of how our government balances power between branches.

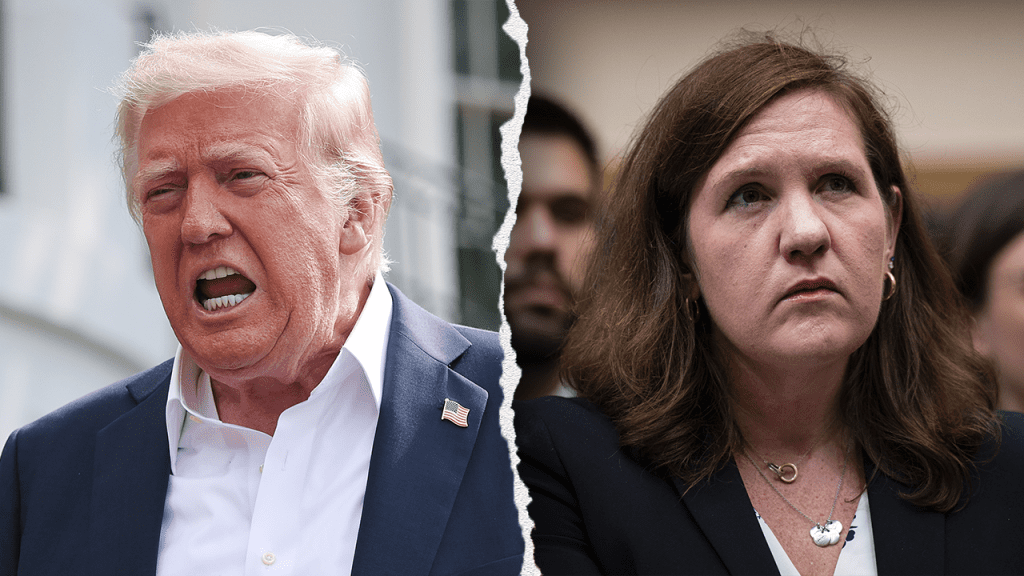

But today, that fabric feels frayed. Trump’s administration argues that the modern FTC is too embedded in executive power to count as independent. The court’s temporary approval to remove Slaughter signals it may be ready to unravel the precedent entirely. Whether justice believes a president’s removal power should be unchecked, or still limited by law, will shape federal agencies for decades.

What really struck me is how this case reflects more than legalese—it’s about who gets to hold power, and how lasting their influence can be. Rebecca Slaughter, appointed by Trump in 2018 and later reappointed by Biden, represents the institutional continuity that independent agencies are meant to safeguard. She and her colleague, Alvaro Bedoya, became symbols of resistance when Trump moved to fire them in March—actions critics called unprecedented, an erosion of accountability. Their reinstatement was relished by those who care about nonpartisan government operations, yet came with the chance that a single stroke of executive authority could unseat them anyway.

Now, with Roberts’s stay, no one can claim the fight is over. The Supreme Court has pressed pause, not stop. Slaughter’s lawsuit continues, and the court has invited responses from her side. How she argues her case—and how the justices interpret both precedent and presidential reach—will echo beyond the FTC. Already, people are watching other agencies closely: the NLRB, the CFPB, even the Federal Reserve.

It matters because we’re at a crossroads in how America ensures fair regulation. The FTC enforces antitrust laws and protects consumers—its independence is essential to unbiased enforcement. If future commissioners can be replaced at a president’s will, the line between policy and political patronage blurs. For me, that precarious balance feels uncomfortable. I imagine parents and workers, wondering if their consumer protection watchdogs will change with the wind, rather than stay firm in their duty.

Even as I write, I picture the faces inside the FTC office: people trying to do their jobs amid chaos. And on the other side, those cheering this ruling as reclaiming executive clarity—believing a president must be able to direct his government. It’s a tough balance between democracy’s two needs: stable institutions and accountable leadership.

For now, Commissioner Slaughter may be gone again. Yet, the law hasn’t spoken definitively. The Supreme Court has given interim power, but not final justice. That’s where this story really lives: in the tension between now and what’s next. The path Trump and his administration walk—to fire agency officials and reshape how power flows—is part of a larger reckoning of executive authority in our time.

When this history is written, people will look back on today as the moment when a 90-year precedent found itself on the chopping block. Whether it falls belongs to the full court’s judgment. For today, all we have is this temporary reprieve—for Slaughter, for the commissioners who follow, and for whichever side of this debate you stand on.