Trump Administration Pushes Two‑Year Limit on Section 8 and Public Housing—A Move That Could Leave 1.4 Million Families Without a Home

I still remember scouting apartments with my best friend, Sarah. We clutched our Section 8 vouchers in hope, but finding a landlord that accepted them felt like chasing a ghost. Now imagine being told, after finally securing a place, that your support would vanish in two years—no matter your situation. That’s exactly what the Trump administration’s recent proposal threatens to do, and the more I learned, the more it hit me: this isn’t just policy jargon. It’s lives on the line.

In May 2025, the White House introduced its budget for fiscal year 2026—a slimmed-down version known as the “skinny budget.” Amid cuts across various departments, what caught my attention was the housing proposal that would cap Section 8 vouchers and public housing at just two years for able-bodied adults. Yes, two years. That’s a blink in the life of someone struggling to escape poverty, manage a disability, or raise a family in today’s cramped and costly housing market.

Think of Section 8 as more than a subsidy. For people like Sarah, and the millions who rely on these programs, it’s breathing room—an assurance that rent won’t consume their every paycheck, a foundation to build on. But housing advocates warn this two-year limit could backfire brutally. A recent NYU study, shared with The Associated Press, indicated as many as 1.4 million households—many of them families with working parents and kids—could lose their shelter overnight. That’s a staggering number—a generation of children and hard-working adults suddenly left without stability.

HUD Secretary Scott Turner defended the plan, arguing HUD wasn’t meant to be a permanent crutch. He said the goal is to spark independence, not dependency. But imagine what happens when the clock runs out. Your local rent costs haven’t dropped. Your job paychecks remain tight. You have nowhere else to go. The people most impacted aren’t ones avoiding work—they’re working low-wage jobs, often two shifts a day, simply trying to stay afloat. Take a mother like Havalah Hopkins, a single mom from Woodinville, Washington. She makes around $18 an hour catering, living with her autistic teen son, paying a tight but manageable rent of $450. She said this cap is “dehumanizing” and would likely leave her family homeless.

Supporters claim other pilot programs show promise. Places like San Mateo County, California, tie a five-year limit to voucher use, as long as participants enroll in counseling and job training. But, and it’s a big one—most of these programs folded, citing lack of funding, growing rents, and limited support resources. And remember, those were five-year timelines. Two years? It seems painfully short, almost punitive.

Then there’s the technical side. The budget doesn’t just cap time—it also shifts HUD funding into block grants to states, slashing about 43 percent of existing housing aid. That means billions less for renters, landlords, and public housing authorities. The result? Landlords may drop out of voucher programs, city budgets will get strangled, and in many communities—especially where affordable housing is scarce—it could ignite a full-blown housing crisis.

It’s not just hypothetical. This proposal has prompted cities like Atlanta to freeze rent increases tied to Section 8 renewals, worried landlords might stop accepting vouchers altogether. Housing authorities are scrambling, not sure how to support existing tenants or whether they’ll lose funding next year. It feels like watching a slow-motion collapse—tenants anxious, landlords rethinking deals, agencies trying to fill the gap.

What I keep thinking about, though, is why this matters beyond charts or dollar signs. Because housing isn’t just shelter; it’s peace of mind. Imagine the stress of knowing you have one chance at stability, that in 731 days your support could evaporate. It’s like playing life’s highest-stakes gamble—with your children’s well‑being as the ante.

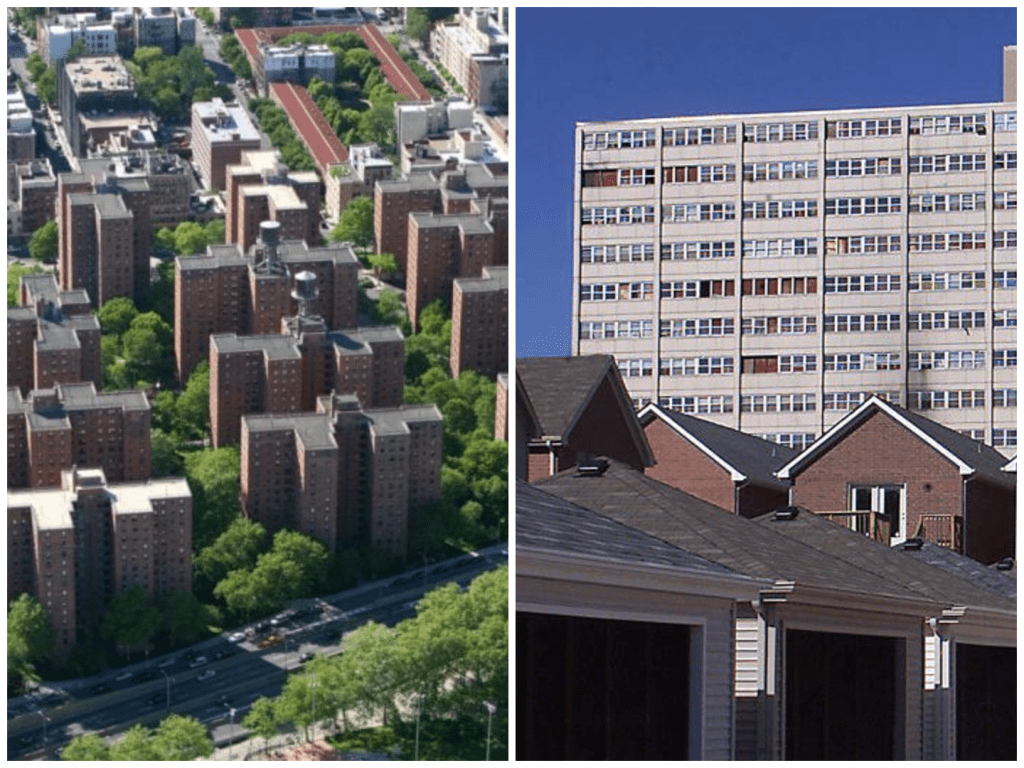

Critics say HUD’s mission always included time limits. But historically, assistance was meant to be flexible. Families tended to stay in subsidies for an average of six to nine years. Forcing a uniform two-year barrier removes nuance and erases the differences in life journeys. Critics also argue that stable housing isn’t just moral—it’s practical. Consistent shelter improves kids’ school performance, health outcomes, even job stability down the road. Strip that away, and you’re causing long-term damage to communities.

What about the program’s intent to spur independence? It sounds fair—help people get on their feet, not stay indefinitely. But it assumes everyone starts from the same place. Not true. Many live in areas with limited job opportunities, poor transit, underfunded schools. You can’t force stability by just removing support. You have to build it—through education, childcare, job training, health services, and affordable housing supply. Limiting time without investment is like pulling the ladder up while someone’s still climbing.

Now Congress gets the final say. Some House Republicans support the cut, but there’s fierce opposition from both Democrats and moderate Republicans. President Biden’s HUD budget, out this spring, kept funding flat and focused on widespread affordable housing needs. We’re on the precipice of a battle over what federal housing aid should do—is it safety net or springboard?

This isn’t just a policy debate for think tanks. It’s about whether we all believe housing is a basic human need worth preserving. Whether we see people like Sarah or Havalah or millions of unnamed families as investments, not liabilities. Whether two years is enough time to both toughest out hardship and chase opportunity.

I don’t know what will happen. But I do know this: reducing aid in the name of independence, without giving families the tools to stand on their own, is a gamble. One I’m not sure we can afford.