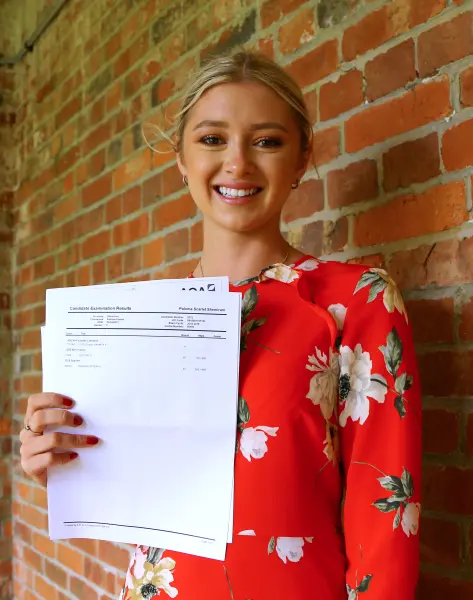

Adversely Influenced”: Coroner Says Mother Played a Leading Role as 23-Year-Old Turned Down Life-Saving Chemotherapy for Five Daily Coffee Enemas

I keep thinking about the quiet moments that must have filled that house: a kettle on the stove, a YouTube video paused mid-claim, a mother’s voice insisting there was a softer way to heal. According to a U.K. coroner’s inquest, a 23-year-old woman with a treatable cancer—told she had roughly an 80 percent chance of recovery with chemotherapy—was “adversely influenced” by her mother to refuse the treatment and follow an alternative routine instead. Five coffee enemas a day became the ritual. The outcomes were exactly what her doctors had tried to prevent. She died, and an official record now says the influence that steered her away from evidence-based care played a “leading role.”

The facts land like a thud because they are so ordinary and so preventable. A diagnosis that arrived with a plan. A medical team offering clear odds, timelines, and side-effect management. And then a detour: a former nurse turned conspiracy-minded influencer, a mother who distrusted mainstream medicine and vaccines, urging a path she believed was purer, less poisonous, more “natural.” In the inquest’s language, there is no gloating, only a careful drawing of lines between what was recommended, what was chosen, and what happened next.

If you’ve ever sat in an oncology ward, you know how hard these decisions are even with perfect information. Chemo is a big word. It scares people. It asks for months of resilience and faith and family logistics and finances and a tolerance for side effects that range from annoying to brutal. So when someone you love leans close and says there’s another way—vitamins, detoxes, coffee poured where it was never meant to go—it can feel like hope wearing a softer sweater. The tragedy here is that the hope was false. Coffee enemas are not a cancer treatment. They come with their own list of risks: electrolyte imbalance, colitis, infection, even burns. They can make a sick body sicker. They cannot target malignant cells or alter the course of a tumor’s biology. That isn’t opinion; it is what decades of oncology has measured and tested and refined.

The coroner’s conclusion matters because it names something many families have felt but struggled to articulate: the pressure of medical misinformation inside the intimacy of a home. It doesn’t always look like coercion. Sometimes it sounds like love—long talks, articles sent late at night, a promise that “this doctor in Mexico” or “this protocol they don’t want you to know about” will save you without the pain. It spreads in podcasts, closed Facebook groups, glossy “wellness” stores, and worshipful comment sections. And it pulls people—especially young people who still want to trust their parents—away from the unglamorous safety of evidence.

There is a heartbreaking counterfactual built into the story. Eighty percent is not a guarantee, but it is a very bright light in a tunnel. Chemo would not have been easy. But it was treatment with a track record and a medical team standing behind it. Instead, the patient spent precious time measuring out coffee grounds and clutching a promise that had never been tested in a trial. The inquest reads like a map of a wrong turn you can’t undo.

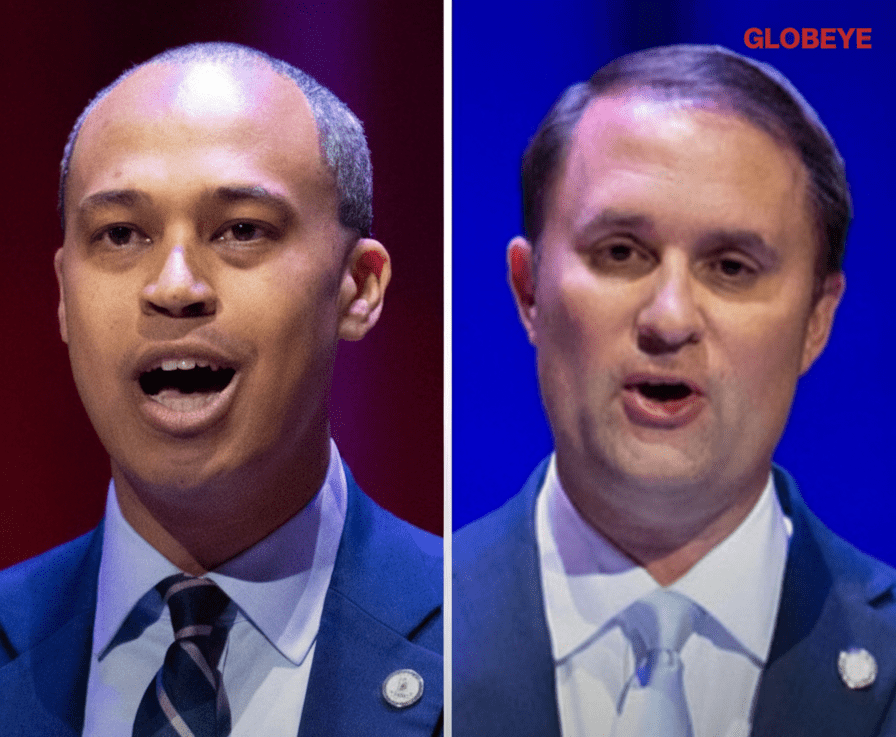

When public figures—particularly those with medical credentials in their past—promote anti-vaccine theories and alternative cures, their words carry a power that isn’t earned by results. A license that has lapsed still reads like expertise to a frightened family. The mother in this case, described as a former nurse and a prominent anti-vaccine advocate, had a megaphone and a loved one who trusted her. The coroner’s language may be formal, but the picture is painfully clear: influence can be lethal when it overrides evidence.

It’s tempting to argue online about this case as if it were a referendum on freedom, as if the choice to accept or refuse treatment exists in a vacuum. It doesn’t. We all make health decisions in networks—parents, partners, pastors, YouTubers, group chats. A strong voice can tip the scale. That’s why second opinions matter. That’s why reputable patient advocates matter. That’s why it’s okay to tell a relative, “I love you, but I’m going to listen to the oncologist,” and to ask the doctor to explain it again, slower, and to put it in writing, and to walk you through the odds with pictures if that helps. Evidence-based care isn’t a demand for blind trust; it’s an invitation to look at what has been proven to work and why.

There is another easy trap here: to turn the grieving into villains. The mother will carry this loss for the rest of her life. The daughter trusted, hoped, and paid the ultimate price for someone else’s certainty. The point of the coroner’s finding is accountability and learning, not spectacle. If anything good can be taken from something this awful, let it be a little more humility about what we claim to know, and a little more courage to ask experts to show us the data before we repeat a cure with confidence.

So here is the gentle plea this story leaves behind. If you or someone you love is facing a cancer diagnosis, keep the door open to questions and to fear, but keep it anchored to clinicians who treat your disease every day. Bring a friend to appointments to take notes. Ask about side effects, clinical trials, timelines, and real numbers, not testimonials. If you’re curious about supplements or complementary therapies, say so openly and let your team check for interactions or scams. And if a voice online promises a painless cure that doctors “won’t tell you about,” hit pause and remember this case. Evidence isn’t perfect, but it is accountable. It has to be reproducible. It gets better because it is forced to prove itself over and over.

A young woman is gone who, by the best estimates, had good odds to live. A coroner has said plainly that misdirected influence helped take those odds away. The orange-glow certainty of conspiracy talk can feel warm when you’re frightened. But medicine isn’t a vibe; it’s work, and it works often enough to be worth the fight. Choose the people who will sit with you in the hard parts and fight for the options that give you the best chance to be here a year from now, five years from now, telling your own story.