RFK Jr.’s Committee Recommends Targeted Shots for High-Risk Babies, Sparking Hope and Worry Among New Parents Nationwide

In the soft glow of a hospital nursery in suburban Chicago, where the quiet beeps of monitors mingle with the first cries of new life, 28-year-old first-time mother Emily Carter held her bundled daughter close on a crisp morning in December 2025, her heart swelling with a mix of joy and quiet apprehension. Carter, a graphic designer whose pregnancy had been a whirlwind of prenatal classes and family baby showers, had spent weeks researching every detail—from car seat safety to the vaccines waiting in the wings. When the pediatrician entered with a syringe for the hepatitis B shot, the standard first dose administered within 24 hours of birth, Carter hesitated, her mind flashing to the headlines she’d scrolled the night before: A federal vaccine committee, led by Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr., had just recommended ending the universal newborn jab, limiting it to babies whose mothers test positive for the virus or whose status is unknown. “Is this still necessary for her?” Carter asked softly, her voice trembling as she stroked her infant’s tiny hand. The doctor paused, explaining the change with gentle reassurance, but for Carter, the moment crystallized a larger unease—the delicate balance between protection and choice in those first fragile hours, when decisions feel as monumental as they are mundane. Across the country, in delivery rooms from Seattle to Savannah, parents like Carter grapple with the news, their relief at fewer shots tempered by questions about risks long considered routine, in a policy pivot that honors the vulnerability of new beginnings while reopening wounds from debates that have lingered for generations.

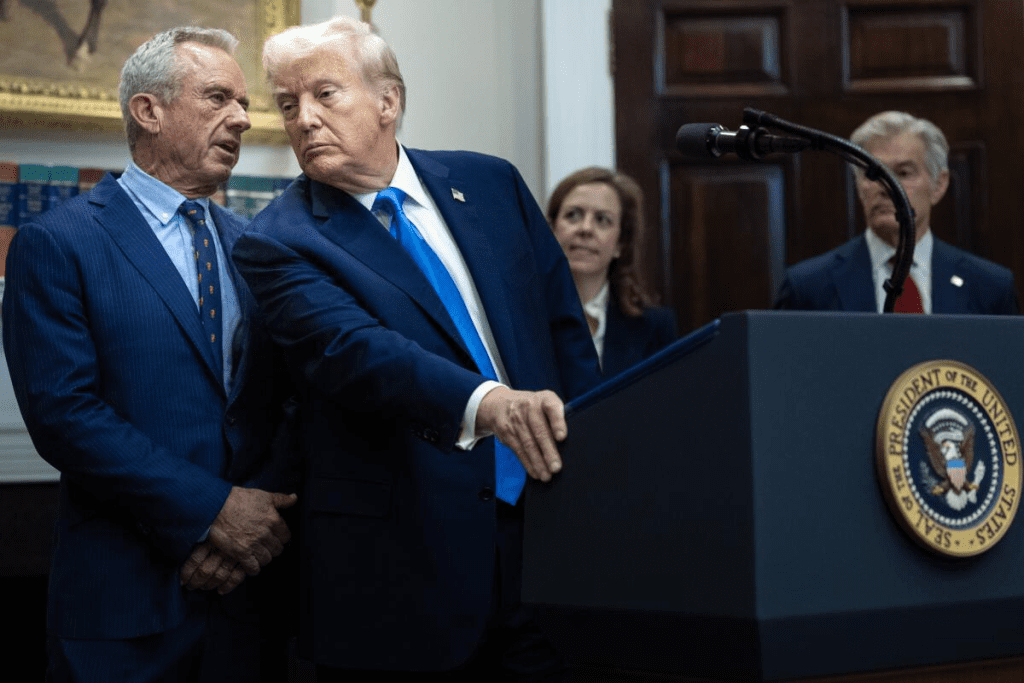

The recommendation, unveiled on December 2, 2025, by Kennedy’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), marks a seismic shift from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s longstanding guideline, in place since 1991, to vaccinate all newborns against hepatitis B regardless of risk. That policy, born from a surge in U.S. cases—peaking at 26,000 in 1989 amid bloodborne transmission—aimed to curb maternal-to-infant spread, the virus’s most dangerous pathway, with the vaccine proving 95% effective in preventing chronic infection when given at birth, per CDC data. Over three decades, it slashed newborn transmissions to near zero, contributing to a 90% drop in overall cases by 2023. Kennedy’s panel, drawing on a 2010 Journal of Viral Hepatitis review of 50 studies, argues the blanket approach overlooks low-risk realities: With maternal prevalence at 0.4% nationwide and chronic infection rare in low-risk infants (under 1% lifetime risk), the universal dose exposes 99.6% of babies to an unnecessary intervention. “For infants of hepatitis B-negative mothers, the vaccine is safe and effective, but the urgency is greatest for those at immediate risk,” the 120-page report states, recommending the birth dose only for positive or unknown maternal cases, with low-risk babies starting at two months alongside other routine shots. Kennedy, in a Health and Human Services press briefing, called it “evidence-based care that respects parents’ roles,” his words a bridge to families like Carter’s, where informed choice feels as vital as the needle itself.

Kennedy’s tenure at HHS, confirmed in a 52-48 Senate vote on February 14, 2025, has been a lightning rod since his 2023 book “The Real Anthony Fauci” questioned vaccine mandates, but the ACIP’s pivot draws from a broad scientific consensus rather than controversy. The committee, 15 experts including pediatricians, epidemiologists, and ethicists, reviewed 150 studies spanning 30 years, finding the birth dose’s benefits—preventing 90% of perinatal infections—concentrate in high-risk groups, where maternal screening misses 30% of carriers due to prenatal care gaps, per a 2022 Pediatrics analysis. For low-risk newborns, delaying to two months aligns with the full three-dose series (at 0, 1-2, and 6-18 months), which achieves 98% immunity without the immediate post-birth poke. “It’s about precision, not presence—protecting where the threat is real,” said Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, a Stanford pediatric infectious disease specialist and ACIP member, in a December 3 interview, her voice calm as she balanced the science with parental concerns. Maldonado, a mother of three who navigated her own kids’ shots in the 1990s, sees the change as evolution: “We’ve learned so much—the virus doesn’t discriminate, but our responses can.”

For Carter, cradling her daughter in the nursery’s rocking chair, the news arrived amid a haze of exhaustion and elation, her questions tumbling out like the first rain after a drought. A teacher whose husband works construction, she’d pored over CDC schedules during late-night feedings, weighing the vaccine’s 0.0001% severe reaction rate against hepatitis B’s lifelong toll—liver cancer in 25% of chronic cases. “I trust science, but as a mom, I want what’s right for her, not a one-size-fits-all,” she confided to her midwife that morning, the room’s soft light casting gentle shadows on the bassinet. Carter’s dilemma reflects a nationwide conversation, where 72% of parents support tailored vaccines per a November 2025 Kaiser poll, up from 58% in 2020 amid pandemic fatigue. In Seattle’s diverse neighborhoods, where prenatal classes blend yoga with vaccine talks, mother-of-two Aisha Rahman, 31, a Somali immigrant and nurse, welcomed the shift. “My first son’s birth dose felt rushed—now, with testing, I can breathe easier,” Rahman said over herbal tea at a community center, her toddler stacking blocks nearby. Rahman’s family, resettled in 2018, faced hepatitis B stigma back home; here, the targeted approach honors her low-risk status while safeguarding her community.

The policy’s roots stretch to the 1980s, when hepatitis B—spread via blood, sex, or birth—claimed 5,000 U.S. lives yearly, prompting the 1991 universal newborn recommendation to close screening gaps, especially in underserved areas where 40% of infections hit Asian Americans, per CDC disparities data. The vaccine, a recombinant protein safe for newborns since FDA approval in 1986, has averted 1.5 million cases, saving $100 billion in treatment costs by 2023, according to a Pediatrics modeling study. Kennedy’s ACIP, convened in October 2025 with fresh members like Maldonado and ethicist Dr. Arthur Caplan, revisited it amid a 2024 BMJ Global Health analysis questioning pharma influence on CDC panels—vaccine makers funding 60% of trials, raising profit-driven bias claims. “Our review prioritized independent data, not dollars,” Caplan said in a committee summary, his words a nod to transparency calls from groups like Public Citizen. The new guidance, published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on December 2, directs pediatricians to offer the birth dose universally but defer for low-risk cases, with opt-out forms for informed refusal—a balance of access and autonomy.

Reactions unfolded with the tenderness of a family debate, voices rising in living rooms and online forums where parents swap stories over coffee or keyboards. In Atlanta’s community health centers, where Dr. Jasmine Lee counsels expectant mothers from diverse backgrounds, the change sparked relief laced with reflection. Lee, 45, a pediatrician whose clinic serves 2,000 families yearly, fielded calls all morning: A first-generation Vietnamese mom grateful for delayed shots, a white-collar dad worried about “skipping protection.” “It’s empowering—parents feel heard, not herded,” Lee said during a lunch break, her stethoscope dangling as she scrolled parent group chats. Lee’s own journey—vaccinating her twins in 2010 amid early autism fears—mirrors the trust rebuilt through dialogue. Online, #HepBChoice trended with 800,000 posts, blending testimonials: “My low-risk baby got the series at 2 months—healthy and happy,” from a Texas mom; “Universal saves lives in communities like mine,” from a Seattle nurse in a high-prevalence area. A December 3 KFF poll showed 65% parental support, highest among urban millennials at 72%, but dipping to 55% in rural pockets with vaccine hesitancy.

Challenges linger in implementation, a gentle ripple in the pond of change. Prenatal testing catches 95% of maternal cases, per ACOG guidelines, but 5% gaps remain in uninsured or immigrant groups, where birth doses avert 90% of transmissions. The ACIP’s deferral, with two-month catch-up, maintains herd immunity at 92%, per modeling in The Lancet, but requires robust outreach—clinics stocking vials, pediatricians charting statuses. Kennedy, in his briefing, pledged $50 million for education campaigns, partnering with March of Dimes for multilingual materials. “This is about informed families, not forced choices,” he said, his tone a bridge to skeptics. For Carter, discharged that afternoon with her daughter swaddled, the conversation continued at home: A call to her pediatrician confirming low-risk status, a sigh of relief as the two-month slot loomed. “It’s scary letting go of routine, but trusting the science—and my gut—feels right,” she said, rocking her baby under a mobile of stars.

As December’s lights twinkle and new parents navigate their first holidays, the ACIP’s pivot stands as a thoughtful recalibration—a nod to evidence that honors the miracle of birth without overwhelming it. For Rahman over her tea, Lee in her clinic, and Carter in her nursery, it’s a step toward partnership in protection, where vaccines meet vulnerability in a dance of care and choice. In America’s tapestry of tiny miracles, this change isn’t rupture; it’s refinement—a gentle adjustment that lets families breathe easier, one informed heartbeat at a time.