The Chicken on Your Plate Has Grown 364% in Just 50 Years—Here’s How and Why It Matters

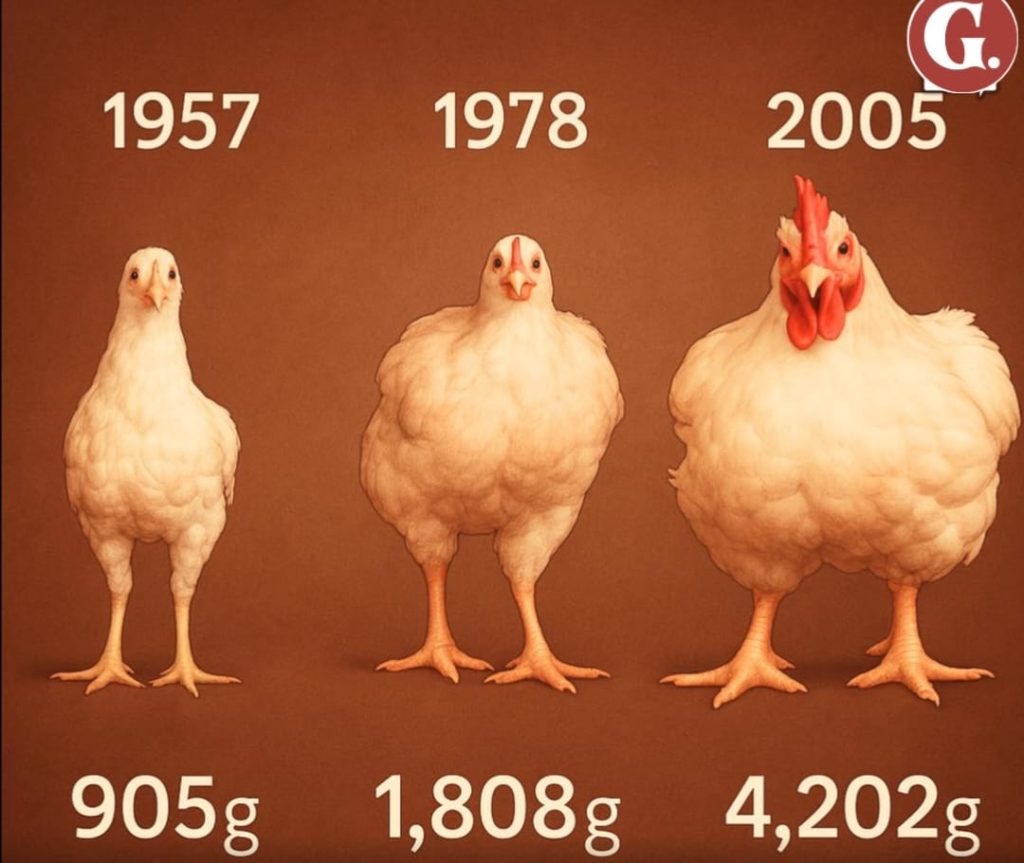

It took me a minute to grasp what I was seeing when I first stumbled on that side‑by‑side picture of chickens from different decades. A scrawny bird from 1957, a slightly more developed one from 1978, and then a mammoth-looking 2005 bird. The numbers underneath were even more jaw-dropping: 905 grams in 1957, 1,808 grams in 1978, and over 4,200 grams by 2005. That’s a whopping 364% size increase. I couldn’t help but wonder—what happened to our chickens? How did we turn a modest, slow-growing animal into a rapid-growth meat machine? And more than anything, what does it mean for us?

How Breeding and Industry Changed the Chicken

To understand this transformation, you need to picture a farm in the 1950s. Chickens then weren’t bred for meat. They were dual-purpose—used for both eggs and a little meat, and they took weeks, sometimes months, to mature. According to a study by Canadian researchers, when chicks from 1957, 1978, and 2005 were all raised on the same diet under the same conditions, the modern breed grew to over four times the weight of its ancestor after 56 days. In other words, this wasn’t just better food or antibiotics—it was breeding itself.

By 2005, chicken companies were engineering birds that don’t just grow faster—they convert feed into meat three times more efficiently than they used to. They hit slaughter weight in half the time. Check the stats: In 1950, broilers reached about 1.8 kg (~4 lbs) in 12 weeks. By 1988, the same weight came in six weeks. And more recently, typical broilers reach 2.7–2.8 kg in just seven weeks.

This growth explosion came from deliberate genetic selection, pushed by consumer demand for cheap, convenient protein. It started with mid‑century programs like the “Chicken of Tomorrow” contest, which encouraged breeders to create birds with a large breast and efficient feed conversion. That spawned breeds like the Cobb 500—birds engineered to grow heavy, fast.

What This Means for Health, Environment, and Animal Welfare

At first glance, it seems like a win. Cheaper chicken, more protein on the table. Indeed, per capita U.S. chicken consumption soared from 16 lbs in 1970 to over 83 lbs by 2013. Feed is used more efficiently, cutting costs and even reducing carbon emissions compared to beef—about 1.5 kg feed per 1 kg chicken, versus over 4 kg feed per kg for pork.

But it hasn’t come without trade-offs. These rapid-growth birds suffer health problems. Their hearts, bones, and joints can’t always keep up with the explosion of muscle. Conditions like sudden death syndrome, ascites, and skeletal deformities are common. There’s also a sad, brutal side of mass production: chickens crowded into barns struggle to walk, with skin lesions and inflammation from lying in their waste.

Then there’s the matter of meat quality. Quick growth means muscle abnormalities like “white striping” and “woody breast”—fat and fibrous tissue that degrade texture and nutrition. These issues have become alarmingly common; by 2018, nearly all U.S. chickens showed some white striping.

Environmental strain also comes with this scale. Barns holding tens of thousands of birds produce massive waste. Studies show ammonia pollution, groundwater contamination, and respiratory issues in nearby communities—yet farms are often exempt from stringent waste regulations.

Why This Matters for You and the Future

Here’s the catch: we might have reached a tipping point. The chickens we consider normal today have been reshaped dramatically in just a few human generations. And while industrial breeding made chicken cheap and accessible, we’re now dealing with consequences. Some scientists and farmers are encouraging a shift toward slower-growing breeds, better living conditions, and even lab-grown chicken—options being developed to improve nutrition and welfare.

This story isn’t just about poultry—it’s part of a larger conversation about food systems. It asks what we’re willing to sacrifice for convenience and cost. In one sense, raising efficient broilers meant more affordable protein. But in another, it means health risks for animals, tools we shouldn’t ignore.

Let me end with this: the chicken on your plate is a living symbol of human influence. In 1950, farmers worked with a slow-growing bird, often in small flocks. Today, our industrial farms raise genetically sharpened breeds in giant barns. That’s not inherently evil—but it’s powerful. And like with any powerful tool, we have to choose how we use it.

What’s next? Maybe more farms will return to older breeds with fewer welfare concerns. Maybe regulations will force better waste control. Or maybe lab-grown chicken becomes the standard. What seems certain is this: the chickens of 2050 will look very different—and so will we.