Coyotes, Climate, and Creepy Rabbits: The Mystery Behind the ‘Zombie Bunnies’ in Fort Collins

I remember sipping coffee on my porch when a friend sent me a photo that made my jaw drop—a wild rabbit in Colorado that looked like it had sprouted black tentacles or quills from its face. My first thought was horror movie meets nature, and my next was, “Is this even real?” As I read more, I felt caught between fascination and empathy—for the story, for the rabbit, and for what wild creatures endure when illness strikes.

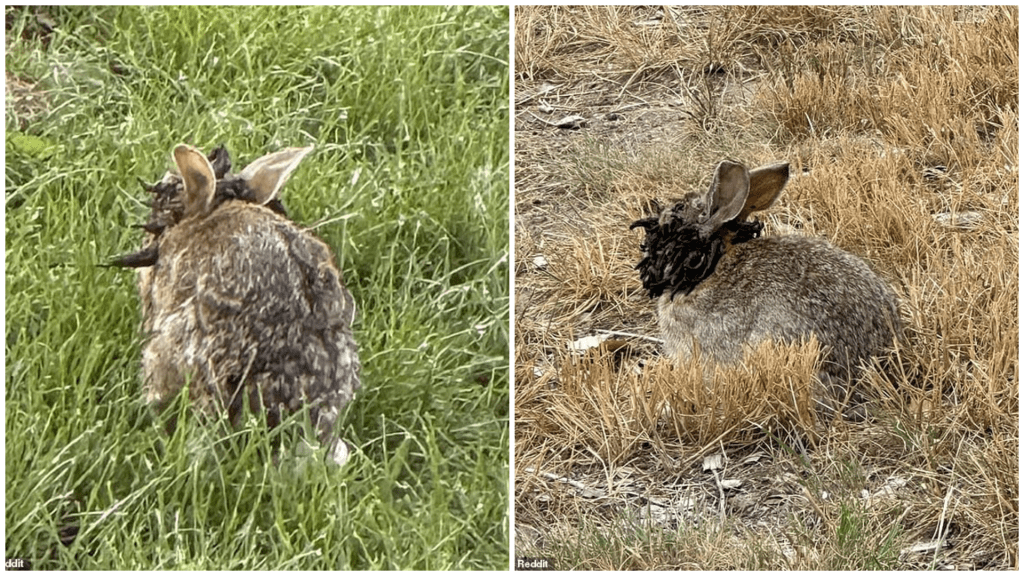

In Fort Collins, Colorado, neighbors began spotting rabbits with alarmingly strange growths around their heads and mouths—clusters of dark, bristly tumors that looked more science fiction than wildlife. One resident, Susan, described the sight as “black toothpicks sticking out all around its mouth,” and she even thought the rabbit might vanish in winter. But to her surprise, the same bunny returned the following year, its growths larger and more pronounced.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife confirmed that these aren’t parasitic tentacles or sci-fi mutations—they’re wart-like tumors caused by the cottontail rabbit papillomavirus, also known as Shope papilloma virus. It’s a rabbit-only virus that creates keratinous growths—warty and sometimes “horn-like”—usually appearing on the head, ears, and eyelids.

Despite their unsettling appearance, officials reassure us that these tumors are not a threat to humans or pets. The virus doesn’t spread between species—only from rabbit to rabbit, often carried by biting insects like ticks or fleas during warmer months. Once temperatures drop, most infected rabbits recover naturally as their immune systems do their work.

What struck me most is how quickly the story spread online—people called them “Frankenstein bunnies,” “zombie rabbits,” even “aliens.” But if we take a breath, it’s a reminder that nature can be both beautiful and bizarre—and often, both at once. As one science-minded voice explained, SPV was actually instrumental in early research linking viruses to cancer. This rabbit virus helped scientists understand how viruses can trigger tumors, and even played a part in later breakthroughs like the HPV vaccine.

There’s a layer of folklore too. Deer antlers, jackalope legends—horned rabbits trace back centuries in both myth and art. Richardson Shope first isolated this virus in the 1930s, studying those “horned” rabbits, and unknowingly fueling the legends that followed.

But back in Fort Collins, the people aren’t just sharing memes—they worry for the rabbits. One resident said, “I feel bad for them,” and I get it. Even if it’s nature’s design, the sight feels sad. Officials encourage us not to touch or feed these animals—just observe them from a distance and maybe let wildlife experts know where you saw one.

For domestic rabbit owners, though, the warning is real. SPV can be more serious in pets, so vets ensure they’re protected from wild encounters and insect bites.

I couldn’t stop thinking how this viral watchfulness mirrors our own—how we grapple with what we can’t comfortably explain. We see a rabbit. Our instincts say “cute,” until our eyes tell us otherwise. We look, then wonder, then learn. And in that arc—from curiosity, to fear, to care—that’s where empathy grows.

The rabbits, for their part, are just living their lives—surviving an infection with immune systems and instincts guiding them through puzzled winters and viral seasons. They become part of a bigger story—our story of how we respond when the wild shows us something we didn’t expect.

Because that’s really what struck me: how nature surprises us with its wildness. And how, in those moments, our humanity shows—when we share photos, tweet with humor, worry a little, and ultimately learn a lot.